We’re looking forward to introducing you to kaya landingin. Check out our conversation below.

kaya, it’s always a pleasure to learn from you and your journey. Let’s start with a bit of a warmup: What battle are you avoiding?

As a 31-year-old millennial senior in Studio Art at CSULB, navigating life on the high-functioning end of the autism spectrum, I’m currently facing a painful reality: younger Gen Z students have been bullying me mocking my age, my neurodivergence, and the very differences that define who I am. Their behavior has triggered deep psychological distress, especially since these acts of exclusion echo past traumas from my childhood in the Philippines.

Back then, I was also bullied for being different. I experienced the fallout of family separation, driven by conflicts among relatives who disapproved of my father. Now, once again, I’m confronting generational and cultural misunderstandings. where people of various backgrounds seem uncertain or unwilling to treat me with the respect I deserve.

It’s isolating. And it hurts in ways that words often struggle to convey. What I’m experiencing today feels harsher and more brazen than what I lived through in the early 2000s. I’m left wondering: how do we build a culture that truly understands difference rather than weaponizing it.

Can you briefly introduce yourself and share what makes you or your brand unique?

I’m Kaya Landingin, 31, autistic senior Studio Art student at CSULB. I express myself through digital drawing, photography, painting, and choreography.

Gen Z peers bully me over age , race, disability, and artistic values. They exploit criticism for online validation. My art defies perfectionism and tokenism. it’s personal, not performative.

Faculty disregard the harassment. My creative practice is survival

Appreciate your sharing that. Let’s talk about your life, growing up and some of topics and learnings around that. What was your earliest memory of feeling powerful?

My early experiences of being bullied in grade school and high school in the Philippines. marked by exclusion, discrimination, and psychological harm set the foundation for a long-standing struggle that continued into my university years at CSULB. There, the dynamics of ageism, ableism, and social gatekeeping within the art department, particularly from Gen Z students and some faculty alliances, reinforced the trauma I’ve carried from the 1990s to the present.

Rather than internalize these repeated cycles of mistreatment, I’ve channeled my pain into movement and making. Dance became my way of reclaiming physical agency; studio art became a medium to process and speak back. Each gym session and brushstroke is not just an act of self-care. it’s my embodied refusal to be erased or misunderstood. The systemic bias I’ve observed where performative vulnerability on social media is weaponized for popularity or deflection. makes it harder to be heard as a Millennial with lived experience.

Still, I move. I create. I advocate. Because even when they don’t understand me or accept me, my existence and evolution are my own.

Was there ever a time you almost gave up?

There was a period at CSULB when I experienced sustained bullying and exclusion, particularly from a group of Gen Z art students and their surrounding social circle. They repeatedly mocked and invalidated my artwork, my neurodivergent identity as someone on the autism spectrum, my race, and my skills. The targeted criticism often masked as peer feedback. gradually eroded my confidence and led me to question my place in the program.

As the harassment persisted, I found myself spiraling into emotional exhaustion: stress, depression, and a deep, simmering anger. I began to lose interest in drawing and painting expressive practices that once brought me joy and purpose. The intent of these students seemed clear: to push me out, to erase me. What deepened the wound was the institutional complicity. Instead of support, I witnessed professors, the dean, the office of Diversity and Inclusion, and even BMAC respond with silence or solutions that protected the aggressors. This broke my trust in faculty and university services meant to advocate for students like me.

Social media dynamics added another layer of harm. The individuals who bullied me re-framed themselves as victims online, using their platforms to spread misleading narratives. My distress whether crying privately or expressing anger was met with further isolation rather than care. I felt deeply unseen. Without meaningful support, it became difficult to continue creating art. Instead, I found refuge in movement: I began dancing outside the university, using that physical expression to reclaim agency and process the immense disappointment of being ignored.

So a lot of these questions go deep, but if you are open to it, we’ve got a few more questions that we’d love to get your take on. What’s a cultural value you protect at all costs?

In the United States, I’ve often felt misread or dismissed not just in my creative expression, but in how I move, speak, dress, and relate to others. My artwork, my choreography, even my communication style. these are extensions of who I am as an autistic artist and dancer. But instead of being understood, I’m frequently judged or critiqued through neurotypical and performative lenses. The discrimination I’ve faced hasn’t only come from peers or art professors at CSULB. it’s also been reinforced by a painful home dynamic.

My biological mother’s repeated gaslighting, manipulation, and emotional invalidation have deeply impacted how I relate to others and how I perceive support. She’s never truly embraced my artistic path whether through dance or painting and instead has contributed to an environment of bullying and emotional neglect. Her actions have shaped how I’ve been treated by others, making it harder for me to find genuine connection. Some people pretend to care, but their concern is performative, often masking deeper biases or discomfort with my identity.

At CSULB, I’ve encountered a similar pattern among Gen Z art students and even faculty. where ageism, ableism, and social politics override empathy. When I express myself authentically, I’m often ignored or marginalized. The cumulative effect of these experiences has made it incredibly challenging to maintain trust, form friendships, and feel safe enough to express my truth. My mother’s inability to truly know or understand me especially since separating from my father during my early school years continues to echo in how I navigate both personal and institutional relationships.

Okay, so before we go, let’s tackle one more area. What do you understand deeply that most people don’t?

Growing up, I began to notice shifts in how I perceived people not just through their words, but through their behavior, tone, and presence. Over time, I developed an acute sensitivity to patterns of dishonesty and superficiality, especially when people would speak with kindness but act with indifference or cruelty. I learned to read between the lines, recognizing when someone was not truly listening or when their intentions were masked behind politeness or performance.

This awareness often left me feeling invisible. not because I lacked clarity. but, because others seemed uncomfortable with being seen through a lens that challenged their self-image. I’ve encountered individuals, both online and in person, who manipulate truth, distort narratives, and rely on performative empathy to maintain control or gain attention. Even when the evidence speaks for itself, many people are quick to believe lies especially when they align with what’s socially convenient.

What stands out to me in human behavior is the fragility beneath the façade: the insecurity that fuels manipulation, the entitlement that justifies bullying, and the silence that enables mistreatment. I’ve experienced these dynamics within my home and at CSULB, where misunderstanding often replaces curiosity, and judgment takes the place of compassion. People have misinterpreted who I am, projected their own biases onto me, and in doing so, they’ve tried to strip away the parts of me that are authentic, resilient, and creative.

Despite this, I continue to see through it. And that clarity is something I protect. Because while others may lose sight of their integrity, I refuse to let go of mine.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://sites.google.com/view/kaylandingin/home

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/dangerous_baby.kay?igsh=NTc4MTIwNjQ2YQ==

Image Credits

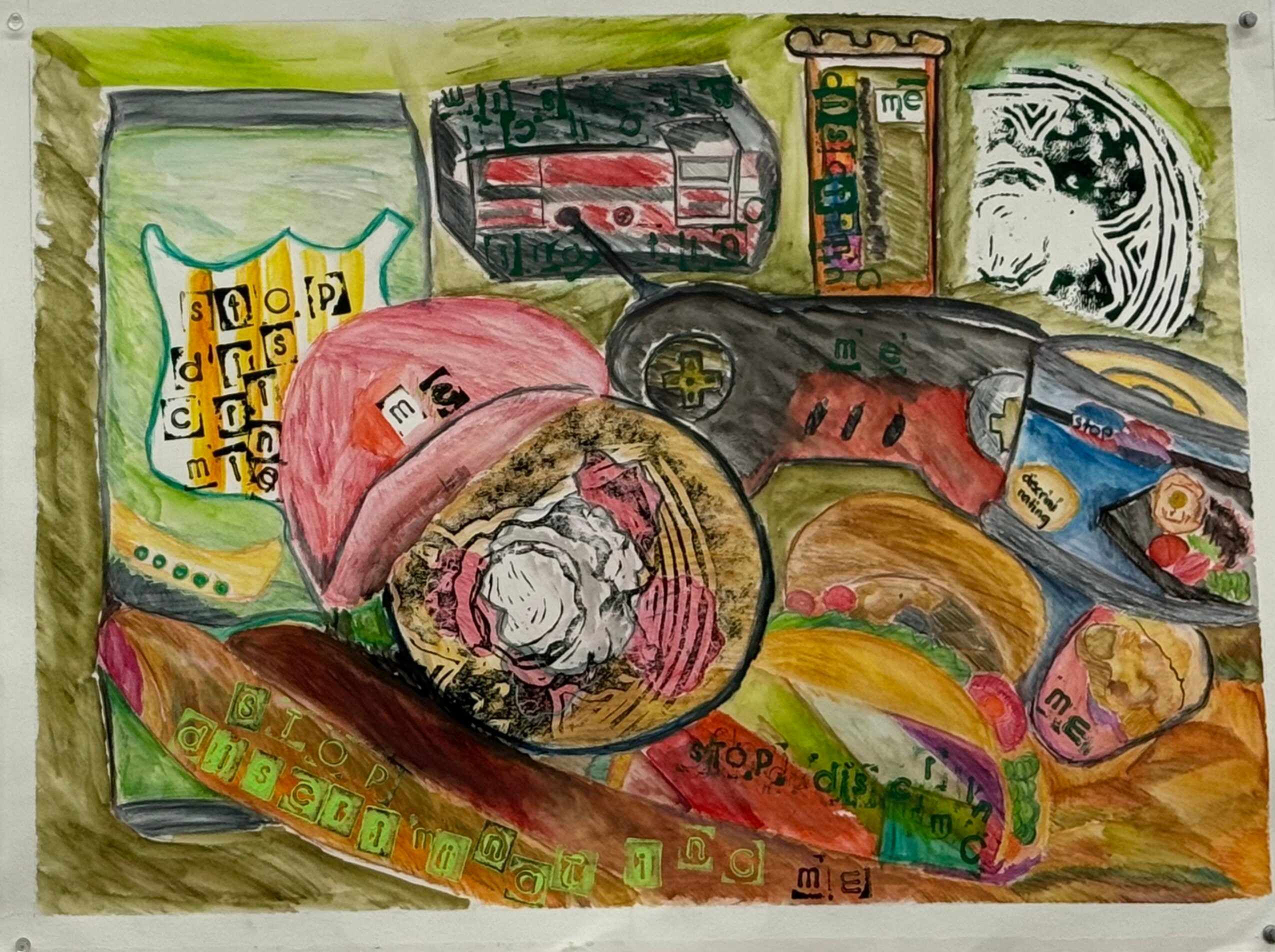

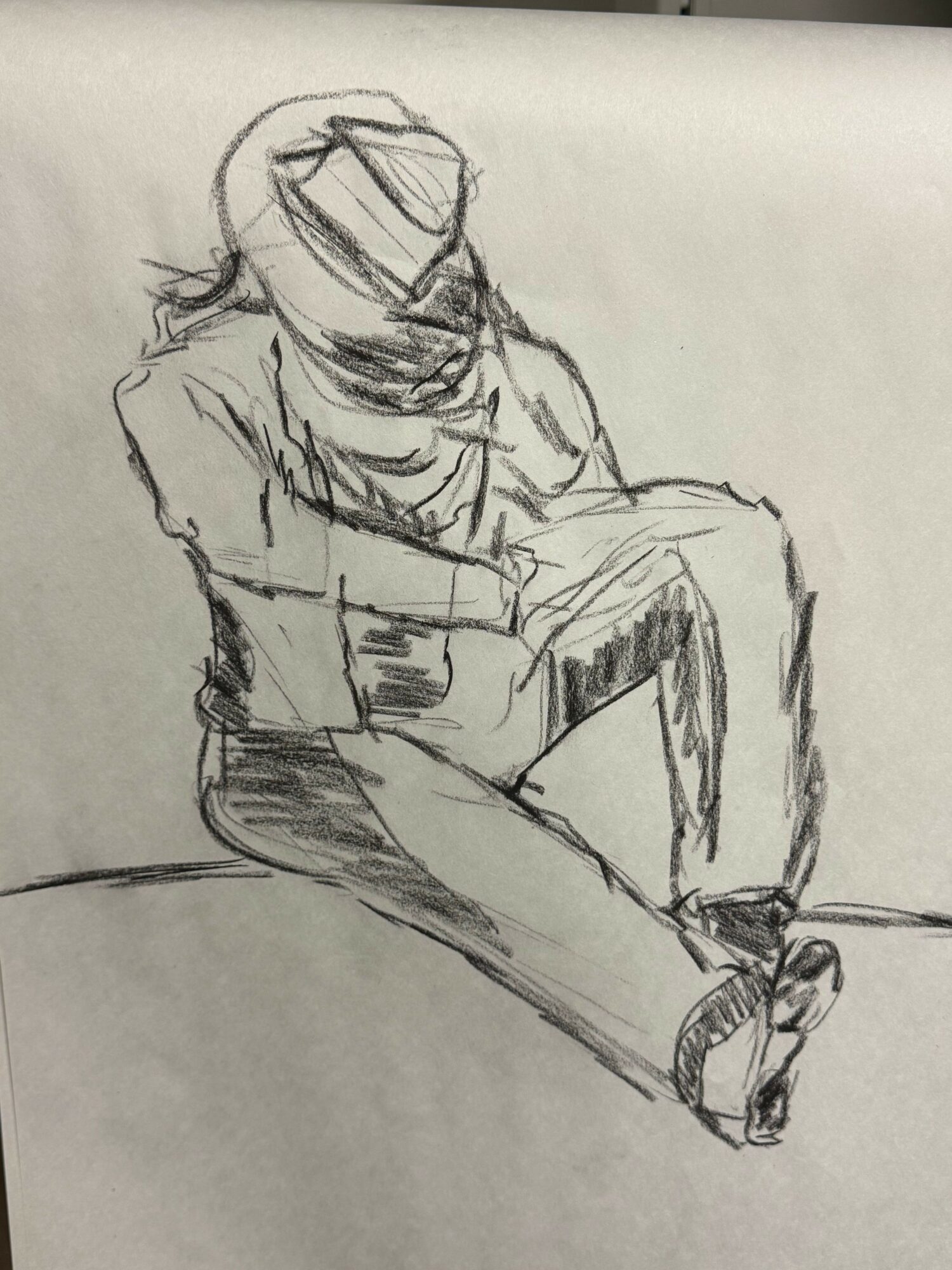

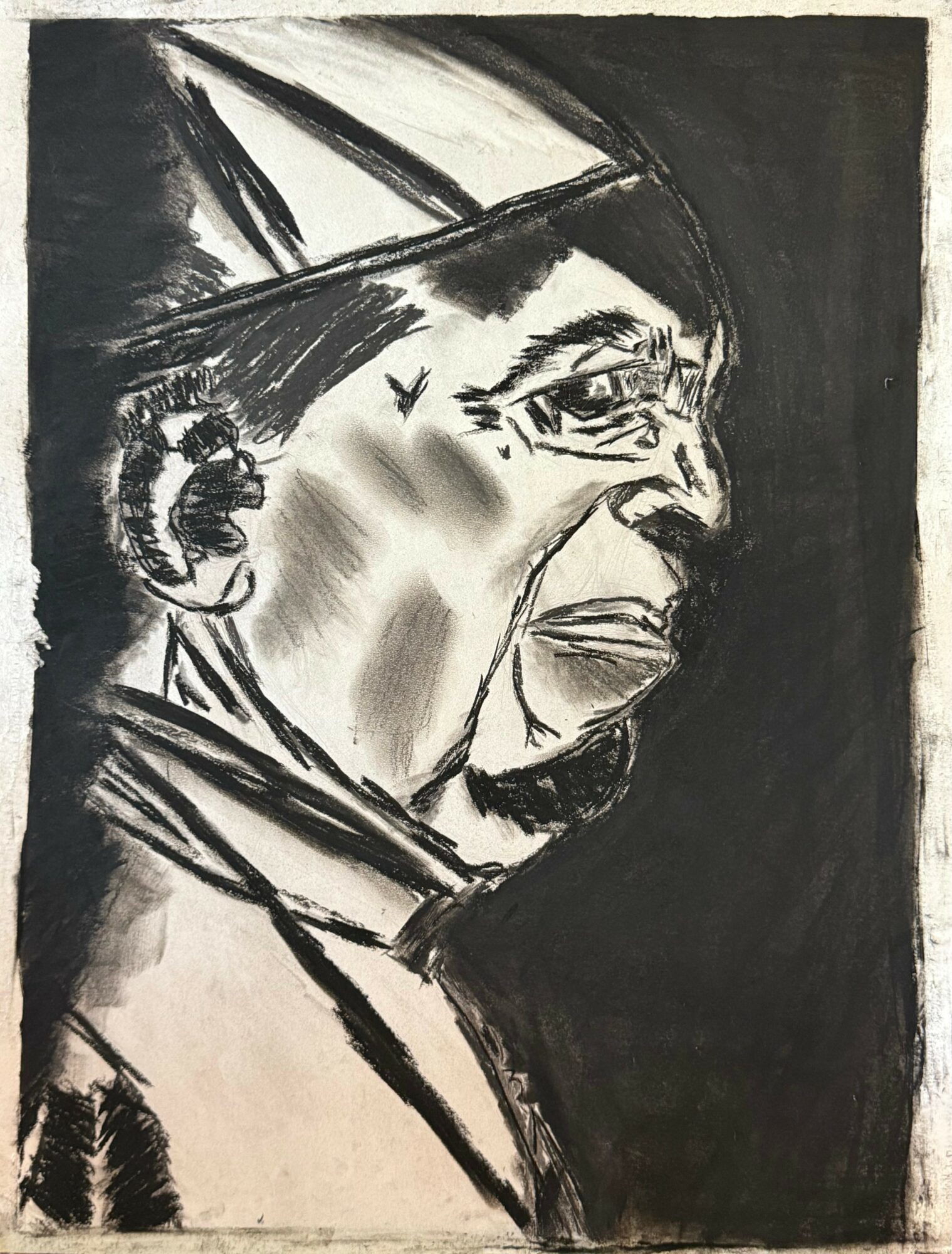

My body of work leans heavily into street, portrait, and nature photography capturing fleeting moments of everyday life and the quiet beauty that surrounds it. Among the images is a personal favorite: a photograph of me dancing in a studio, where movement became a form of release and reclamation. Alongside these visual narratives, I’ve also created several traditional and digital drawings. Each one is a quiet attempt to process my sadness and work through the emotional weight of university life. Art, for me, has been both a coping mechanism and a way to translate frustration into something tangible and honest.