Caroline Stephen shared their story and experiences with us recently and you can find our conversation below.

Caroline, so good to connect and we’re excited to share your story and insights with our audience. There’s a ton to learn from your story, but let’s start with a warm up before we get into the heart of the interview. When have you felt most loved—and did you believe you deserved it?

My first solo exhibition, The Body Is A Situation, opened July 20th, and I am so incredibly grateful for people who came out to see it. This project took months of work, and I felt an unbelievable amount of love from my community once it was put out into the world. It was the first time I had presented such personal work on that scale, and seeing so many people engage with it thoughtfully was incredibly meaningful.

Throughout the months leading up to the show, I had moments of doubt about the work, its reception, and whether anyone would actually come. So when they did come, and they stayed, and had things to say, it reminded me that the work didn’t exist in isolation. It was part of a dialogue.

I’m not always great at receiving support, but that night helped me realize that people showed up because they genuinely cared, not just about the work, but about me. I don’t know if I fully believed I deserved it at the time, but I was, and still am, deeply grateful for it.

Can you briefly introduce yourself and share what makes you or your brand unique?

My name is Caroline Stephen, and I’m a Los Angeles–based artist working primarily in photography and sculpture. My work explores the performance of femininity, domesticity, and emotional labor, often tracing these expectations back to their origins in the social conditioning and symbolic play of girlhood. I’m interested in how mimicry becomes a tool for self-preservation and how performance can shape, distort, or protect identity.

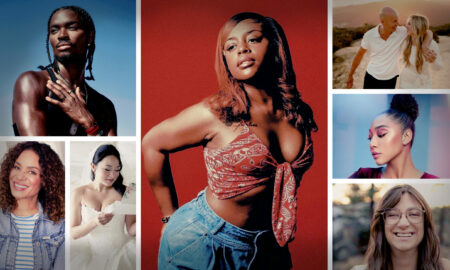

I recently opened my thesis exhibition, The Body Is A Situation, a series of six self portraits portraying myself as caricatures of women, elaborately costumed and photographed against monochromatic backdrops. The figures depicted in these photographs derive from real people or characters from media I have resonated with, and therefore the work exists as a process of constructing identity. The project wrestles with both artifice and reality, revealing an unsettling intersection where personal identity and mimicry converge. In these images, gender is an ongoing performance, one upheld through affective labor and adherence to culturally produced expectations.

Alongside my photographic work, I also create sculptures that examine similar themes, often using domestic images or familiar childhood forms to evoke feelings of distance, disorientation, and quiet violence. These sculptural pieces explore what it means to construct a version of home or girlhood that is at once comforting and unsettling, staged and intimate. I see both parts of my practice as intertwined ways of thinking about memory, absence, and the roles we are asked to perform.

Appreciate your sharing that. Let’s talk about your life, growing up and some of topics and learnings around that. Who taught you the most about work?

I’ve learned the most about work by watching the women around me, particularly those who were never formally recognized for the labor they performed. Growing up, I saw how much energy was spent on holding things together behind the scenes: maintaining appearances, managing emotions, keeping everyone else comfortable. It wasn’t framed as work, it was just expected. But it shaped the way I understand effort, performance, and endurance. That kind of invisible labor, emotional, domestic, and often gendered, has informed not only how I approach my life, but also how I think about making art.

At the same time, I’ve been shaped by artists and mentors who modeled a very different kind of work, one that values reflection, intentionality, and personal stakes. I’ve learned that showing up for your practice consistently, even when no one is watching, is a discipline in itself. That rigor doesn’t always look like producing something tangible every day. Sometimes it’s reading, observing, or just sitting with discomfort long enough to understand what it’s asking of you.

So I suppose I’ve learned that work isn’t just what you do, it’s how you hold yourself in it. It’s how you choose to give your time, your attention, your care. And for me, that comes from a lineage of women whose labor went unnamed, and from the artists who helped me name my own.

What fear has held you back the most in your life?

The fear of failing, and more specifically, the fear of letting myself down, has held me back more than anything else. I’ve always put a lot of pressure on myself to meet a certain standard, not just in terms of outcomes, but in how I carry myself, how I move through the world. I internalized this idea that if I didn’t do something perfectly, it wasn’t worth doing at all. That mindset has made me hesitate. I’ve delayed projects I cared deeply about, avoided risks, and stayed silent in moments where I should’ve spoken up, not because I didn’t have something to say, but because I was afraid it wouldn’t come out the right way.

What’s hardest is that I don’t need anyone else to criticize me, my own expectations can be the most punishing. And when I fall short, I turn inward and isolate, as if disappointment is something I deserve to sit with alone. Over time, I’ve realized that part of growing up, and growing as an artist, is learning to show up even when the work is imperfect, even when I’m uncertain. I’m still working on that. But I’ve come to understand that failure isn’t the worst thing, it’s the silence, the inaction, the self-erasure that happens when you don’t give yourself the chance to try.

Sure, so let’s go deeper into your values and how you think. Whom do you admire for their character, not their power?

Dolly Parton! She’s someone who has remained grounded, generous, and radically kind, despite decades of fame. What I find most admirable is how she balances self-awareness with sincerity. She leans into artifice, the big hair, the rhinestones, the persona, but never at the expense of substance. She’s built her identity on performance without ever feeling fake. That’s rare.

Beyond her image, she’s quietly done so much good — funding education programs, giving to communities in need, and helping create space for people who don’t always feel seen. And she does it without seeking praise. There’s a humility in the way she moves through the world that makes people feel safe, seen, and respected. In an industry that rewards ego and spectacle, she’s built something lasting out of compassion, humor, and integrity.

Thank you so much for all of your openness so far. Maybe we can close with a future oriented question. How do you know when you’re out of your depth?

I try to surround myself with people who are smarter, and more creative than me. That way I’m always learning from the best, and I can contextualize whatever I do. I usually realize I’m out of my depth when I stop feeling curious and start feeling like I have something to prove, when the work becomes about trying to keep up rather than staying connected to my own voice.

It used to make me panic (and it still does sometimes). Now, I try to take it as a signal that I’m in the right room, that I’m being challenged in a way that stretches me. Feeling out of my depth usually means that I’m about to grow, even if it’s uncomfortable in the moment. I don’t think you can make meaningful work without being willing to sit in that discomfort sometimes.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://carolinestephen.com/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/c.g.s/