Today we’d like to introduce you to Ollin A. Ramirez.

Hi Ollin A., please kick things off for us with an introduction to yourself and your story.

My name is Ollin Ramirez, a weaver and painter from Los Angeles, CA. For the majority of my life, I was raised in South Central, L.A. with frequent trips to El Salvador to where my family was from and mainly still located. These trips back home played a paramount role in my practice as an artist, with the breadth of my work focusing on my family history as well as my own intersecting identities.

As early as I can remember, I have always taken a liking to any form of creativity. My earliest works took form as color pencil and marker drawings of my favorite Pokémon creatures; in what I would describe as epic battles. It wasn’t until my teenage years I began to look at art through a more critical lens. I began painting in acrylics and studying art history alongside contemporary examples of what was being created today. In these early years, my paintings focused on my parents, mainly my mother, who was working in LA as a nanny. I was enthralled with the ideas of representation and used my art as a tool to shed light on what I believed to be one of the invisible workforces of LA. After graduating high school, I moved to Northern California for school with the goal to major in Painting and Drawing.

I received my BFA from the California College of Arts in San Francisco. During my time there, I expanded on my vision and began working with oils. The newly developed distance between my immediate family and I began to reflect in my work. The focus of my paintings began to shift toward my family in El Salvador and my parent’s journey to the United States. My paintings became a way for me to fill the gap created by distance; physical manifestations of my family. I was, and still am yearning to feel more connected to my familial history and land. Much of our family history has been erased due to war and the attacks on our indigenous communities in El Salvador. My paintings became a necessary act to document what I feel is an authentic history of family and community in El Salvador.

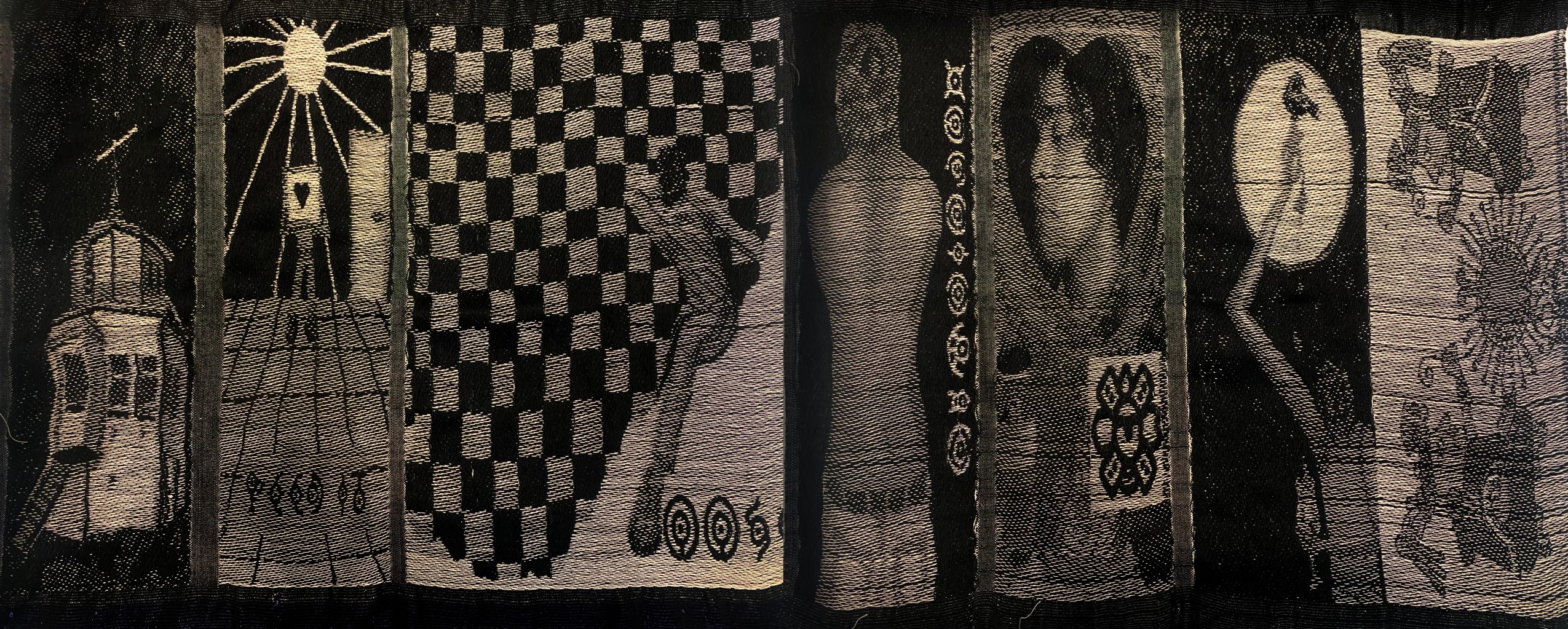

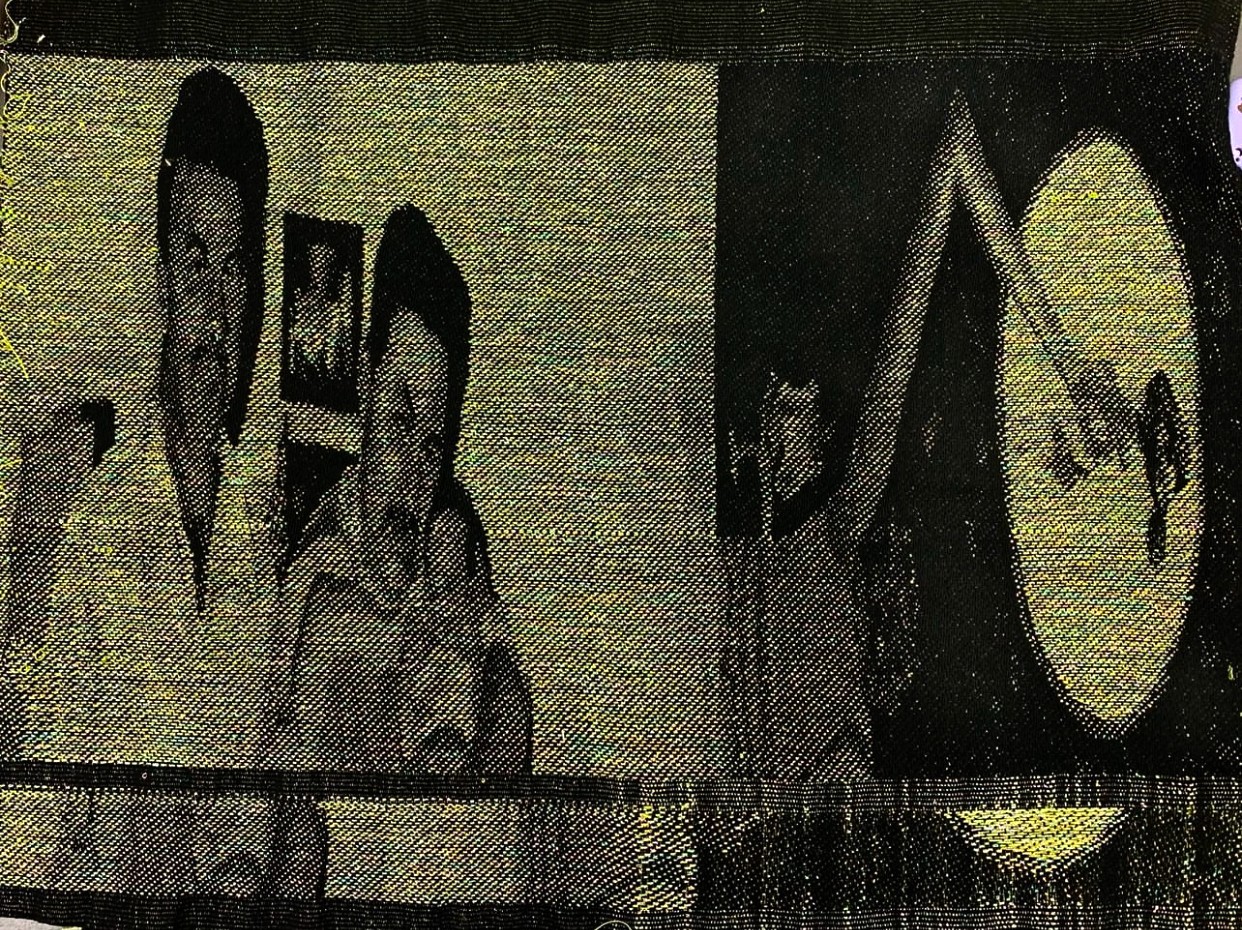

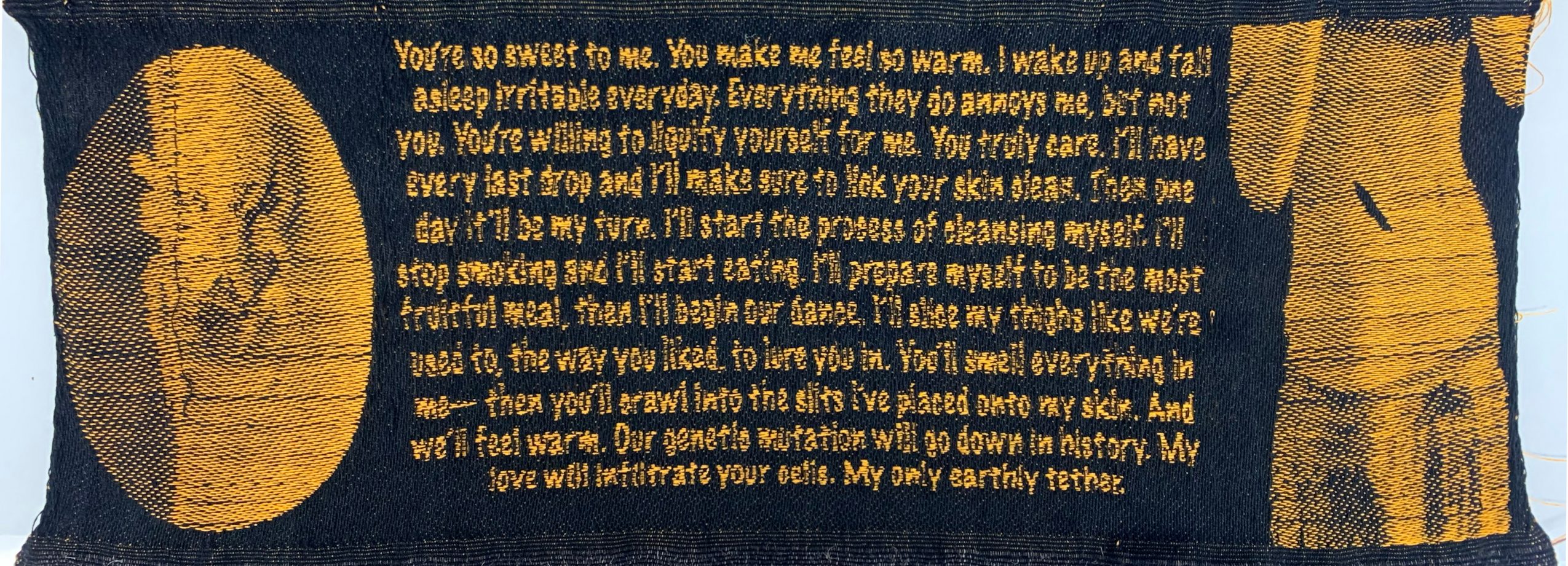

While studying at CCA, I began to focus on and study textile arts, primarily weaving. I fell in love with the manipulation of threads. Like a spider building her home, weaving felt like a practice rooted in ancestral knowledge and love. As a weaver, I felt I was able to connect myself to a larger conversation to a certain cultural femininity. I felt embraced and affirmed as a queer artist. My textile work focuses much more on my own body and experiences living today. It provided me with a way to navigate expressing my own traumas through a soft practice. The imagery in my weavings comes from my drawings, photos, pop culture references, and symbols derived from our Mayan and Aztec roots.

I’m sure you wouldn’t say it’s been obstacle free, but so far would you say the journey have been a fairly smooth road?

My body has always been central to me. It has been an aspect of my life that I’ve always been cognizant of. The hyper-awareness was poignant and painful. It was obsessive and parasitic; leeching off all my energy. The relationship I felt with my physical body was estranged and I regressed into a place where I had felt displaced within myself and unwanted within a larger sphere. I rejected many parts of myself and poured what little was left into my work and my livelihood. Back then, I was trapped, my room was a cube. In the cube I had an easel and my paintings; it was my only form of resistance. For years, the isolation stole my memories and twisted my perception of ‘self.’ I began to resent my body, and I craved to feel empty. I dejected all notions of roundness, of softness. Control was about form, it was about aiming for the perfect shape. My body with its curved, nutritious shape, resembling my family, and sculpted in the language of maternal, was the opposite of what I was striving for.

After about two years, my body began to slow down and I felt as if I was beginning to decay. I had lost so much of myself I was unsure of what to do next. My morbid attempt to ‘fix’ my body had left me in a much worse state; regret and embarrassment followed me. My body now felt rigid and unfamiliar, my bulging rib cage made me feel alien— like I had morphed into something other-worldly. A creature adapted to a lack of love and nourishment.

I turned to textiles – it had everything I lacked. It was soft and plush, it was friendly and warm. I began to crochet and knit again, just like how my abuela taught me when I was young but resistant to learning. Now though, I needed the embrace of yarn to contrast my harsh form. I crocheted non-stop, and I began to eat again. The yarn taught me to embrace myself, each stitch a prayer and plead to some place divine.

It is a moment in time I hold dearly within my heart; the first time I dressed a loom and wove my first lines of weft. Agency began to come naturally. My body no longer felt strange; maybe it wasn’t even me anymore. I was entranced with the loom, and I melted every molecule of my being to merge with the loom. We understand each other, and we begin to talk. The loom tells me of myself, it is a reflection of my emotions. The loom responds to each sensitivity of my touch to guide it and the strings. Too much tension and I risk snapping a thread, but not enough and it will be a weak piece of fabric. And the loom was the one who decoded my gender, it was the first entity to refer to me correctly.

My ancestors were weavers. Crochet and knitting were introduced after contact with Spain, and I believe this is their way of communicating with me. When I weave I can feel a feminine embrace in my veins. I know it is ancestors working through me and validating my gender expression. Weaving is historically a women’s craft, and it has allowed me to tie myself to a larger sphere of cultural femininity from El Salvador.

Weaving is a pre-colonial practice and has helped indigenous women survive and care for their communities and families. Weaving has taught me how to care for myself, and it has reminded me that my body is capable and deserving of love. I owe my life to textiles and to my teachers who have taught me my crafts.

Can you tell our readers more about what you do and what you think sets you apart from others?

My ancestors were spiders as well. They were weavers, some of the first to create with natural fibers. La naturaleza fed, clothed, and informed us. Plants were used medicinally to heal our people, and they provided the fibers needed to clothe and protect us. It was my first time weaving, but my soul understood the motion of throwing weft after weft. It felt natural and it was familiar. My body was new to weaving; it was, and still is, a student learning the processes and intricacies of weaving, of interlocking strings, but within I understood it was a reuniting and not an introduction. Weaving is my ancestor. It is my teacher. My friend. A mother. Tejidos provided me with the tools to love and care for myself.

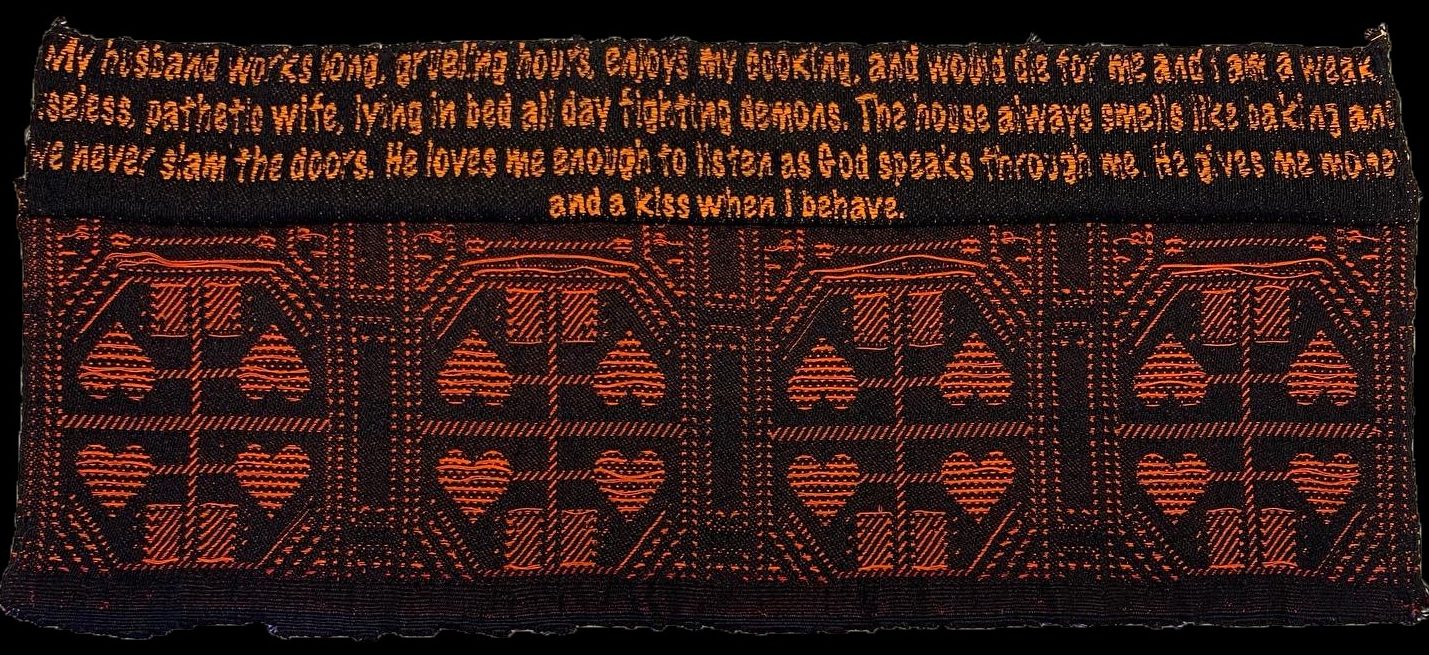

My weavings allow myself to explore deep within myself. In ways that feel unthreatening and unrestricted. They venture deep into the intricacies of the physical journey my body has been through and often act as visual indexes to decode and explore my own gender identity. The text found in my weavings come from my own journals and sketchbook and are intimate and intentional with their language. They show a yearning for a physical alignment with my body that is more feminine and delicate. They speak of imagined husbands and scenarios of intimacy. I utilize many symbols and glyphs descended from Mayan and Aztec roots. A prominent glyph seen in my work is Nahui Ollin, with a variety of meanings. Nahui translates to ‘four’ and Ollin to ‘movement’; a reflection of the ever-changing nature of my body and the universe. As well as Nawat words written using ‘Unknowns’ from Pokémon, a faux hieroglyphic language used in the game. Playing with a library of symbols and languages to tell a story is what excites me.

Are there any books, apps, podcasts or blogs that help you do your best?

I look mostly to Mayan and Aztec histories when creating my work. I have gotten so much inspiration from the Codices, which were folding books created by pre-colonial Maya civilizations on bark paper. The books were the products of scribes usually working under the patronage of deities. The codices depicted epic tales of gods and forces in Maya culture and the stories of the communities and people. Most of the codices were destroyed by the conquistadors and Catholic priests in the 16th century. The erasure of the indigenous history and stories in Central America has been a big part of my drive as an artist.

Contact Info:

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/oosk.y/?hl=en

Image Credits

Image Credits

Personal Photo by Christine Jubilee. Additional Photos (Artwork) by Ollin A. Ramirez