Today we’d like to introduce you to Kelly Fong.

Hi Kelly, we’re thrilled to have a chance to learn your story today. So, before we get into specifics, maybe you can briefly walk us through how you got to where you are today.

I was born and raised in Oakland, California. My family has been in the Bay Area for several generations. In fact, my paternal grandmother’s family immigrated to the Bay Area in the mid-19th century with other Chinese immigrants from Southern China who were drawn to Gum Saan or Gold Mountain – the Cantonese name for California. I learned bits and pieces of this family history growing up, but I did not realize its significance (both personal and historical) until I was an undergraduate at UC Berkeley in my first Asian American Studies course with Professor Michael Omi. I was intrigued how, for the very first time, I could see my family’s experiences centered in the textbook and lectures rather than as a footnote or not at all: surviving immigration interrogations on Angel Island, working in garment factories and in the fields, and navigating racially segregated spaces in both life and death. I also began to realize how fortunate I was to have had Asian American teachers in second and third grade who planned field trips to Angel Island in the San Francisco Bay and to have had parents who knew enough about our family’s history to tell younger me about why this place mattered.

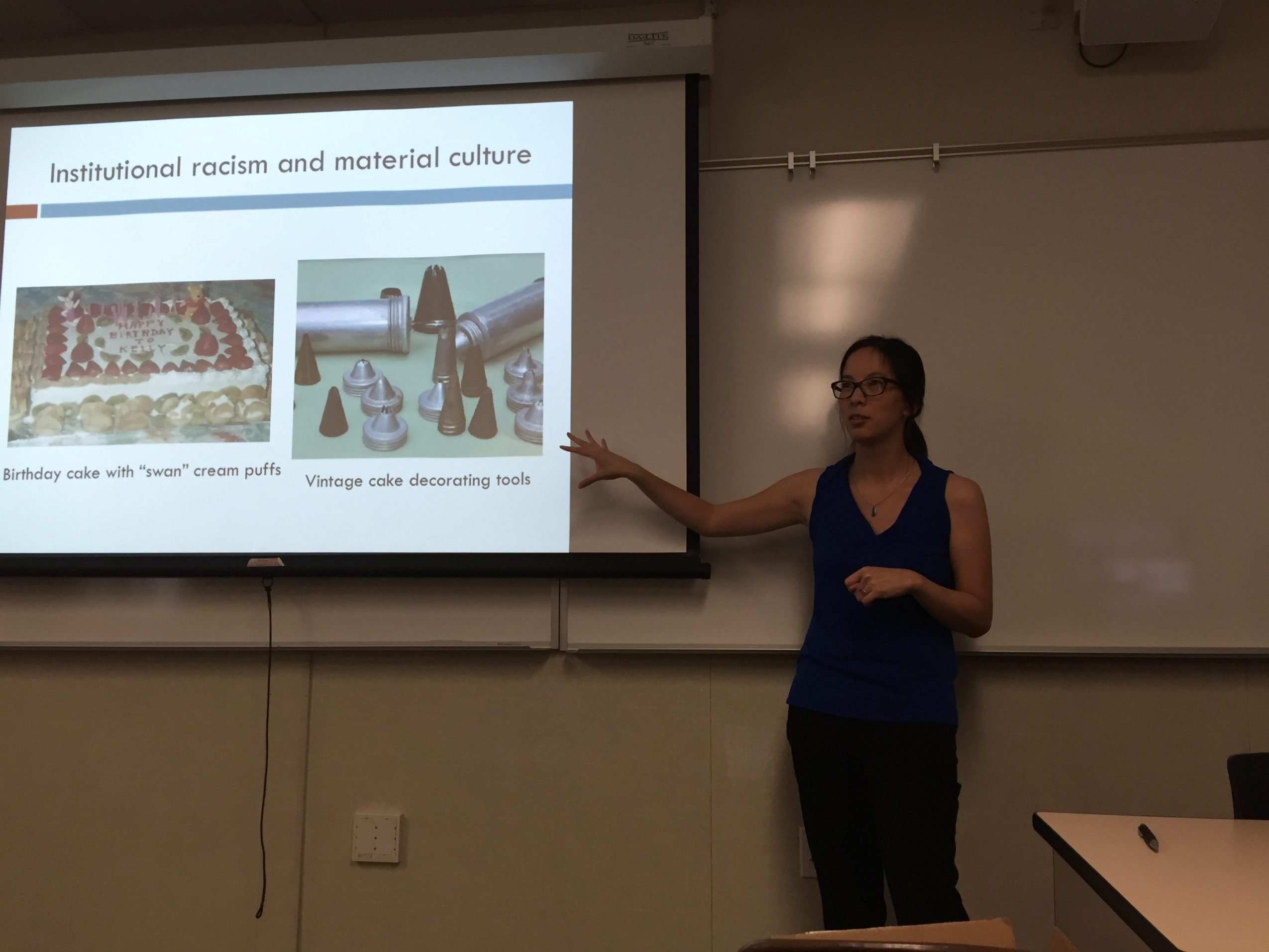

After sparking my interest in Asian American history as an undergraduate, I landed on historical archaeology on accident. I enrolled in an introduction to archaeology course to fulfill a general education requirement with Professor Laurie Wilkie, fell in love with historical archaeology, took an upper division course on American material culture with Laurie, and had a life-changing moment in a single lecture focused on the little archaeology that had been done of Chinese American communities. I walked away from that lecture recognizing that my intersecting interests in archaeology and Asian American Studies opened brand new possibilities for interdisciplinary work to study historical archaeologies of Chinese American communities. I declared my Anthropology major and Asian American Studies minor, began running with it, and haven’t stopped since.

I am currently a continuing lecturer in Asian American Studies at UCLA and co-project director of Foundations and Futures: Asian American Pacific Islander Multimedia Textbook at the UCLA Asian American Studies Center. As a contingent faculty member, I’ve taught in multiple departments at multiple universities across Southern California over the past decade. I regularly teach large, lower-division courses that introduce students to Asian American Studies for the first time. Many of my students don’t realize how personally meaningful the class will be until they are in the course. I love sharing those moments of excitement and inspiration when they connect their own lived experiences or those of their family to what they are learning about in course readings and lectures. After those moments, there’s no going back to life without Asian American Studies.

Alright, so let’s dig a little deeper into the story – has it been an easy path overall, and if not, what were the challenges you’ve had to overcome?

It definitely has not been a smooth road! My journey through archaeology has not been easy. There are not many BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) archaeologists in the field more broadly, and there were even fewer Asian American archaeologists studying Asian American historical archaeology when I entered the field in the early 2000s. As far as I know, I was the first Chinese American studying Chinese American historical archaeology to earn a Ph.D. Fast forward to today in 2024, our number is up to two of us, with at least two more Chinese American archaeologists currently in doctoral programs. When I entered the field, I also approached this work from a very different perspective than other scholars by centering an Ethnic Studies and Asian American Studies framework and my own subjectivities as an Asian American woman and member of the descendant community. Navigating a predominantly white field from this perspective meant facing a lot of pushback from colleagues who were not ready for these conversations and/or dismissed my work as too subjective or too much of a downer. Two decades later, there has been some improvement to having conversations about race and racism or better understanding why it is essential to recruit, train, and retain Asian Americans in the field, but there is much work to do. I’m proud to have been a part of this growth, whether this has been recruiting and mentoring fellow Asian American archaeologists, speaking openly about my experiences, or working with wonderful colleagues in the Coalition for Diversity in California Archaeology (CDCA) to push the boundaries of what a truly inclusive field may look like in our ongoing struggle for institutional change.

My experience as contingent faculty has also been a struggle. While there recently have been more conversations about the hierarchy of the academy in light of labor organizing and the inability to make a living wage, many students don’t realize how many of their instructors are faculty who get hired term to term to teach a class with little to no job security and low pay. In some cases, I’ve invested countless time and energy into developing and teaching a course only to never be hired again. Those syllabi sit filed away on my computer and collect e-dust. I am extremely fortunate to have built a place for myself in Asian American Studies at UCLA and to have a department that values the work of its contingent faculty, but it also required enduring 18 quarters of precarity over nine years before acquiring job security with a promotion to continuing lecturer.

Thanks for sharing that. So, maybe next you can tell us a bit more about your work?

On campus, I’m most well-known for my teaching, especially among students. Teaching isn’t an easy profession, especially juggling different class sizes that range from 20 to 250 students. I’ve built a reputation among students who say they find my lectures and assignments engaging, inspiring, and personally meaningful and tell their peers to take my courses. I’m proud to regularly recruit students to the Asian American Studies major or minor, especially students who didn’t realize that they were looking for Asian American Studies until they were in my classroom. I’m proud of the amazing things my former students accomplish as college students and beyond and that I may have had a small part in shaping their undergraduate experiences that they continued to take with them.

Outside of the classroom, I’m involved with several projects that I am also proud of. I’m currently working on Foundations and Futures: Asian American Pacific Islander Multimedia Textbook at the UCLA Asian American Studies Center. Co-directed with Karen Umemoto, this project seeks to bring Asian American Studies into high school, community college, and college classrooms across the country. Despite 50 years of scholarship, a lot of Asian American Studies content remains in college campuses and locked behind paywalls. We are hoping to bring Asian American Studies to broader audiences and to help democratize this knowledge. This project is also timely, coinciding with a nationwide push to include Asian American and Pacific Islander histories and experiences in classrooms, as well as increased media attention since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic on the spike of anti-Asian racism. The project is currently in development, but it will include content, curriculum, and multimedia curated by leading scholars and educators on a range of topics related to Asian American and Pacific-Islander communities and histories. The textbook will be available to all students, teachers, and lifelong learners with an internet connection when we launch the first edition in 2025. We know this project will play a role in changing the narrative about Asian American and Pacific Islander communities and we are excited to get this textbook into the hands of educators and learners soon.

I am also working on several collaborative social history projects focused on Chinese American communities. One project, dubbed “The Five Chinatowns,” examines the five Chinatowns of Los Angeles prior to 1965. I’m working with two Asian American Studies colleagues, William Gow, and Isabela Quintana, along with the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California, to document these Chinatowns, some of which no longer exist today. We have worked extensively with high school and college student interns since 2021, providing training in oral history community-based research and culminating in each intern completing an oral history interview with a community elder. The project will become a book anthology with contributions from our former interns, community historians, academics, and community narrators.

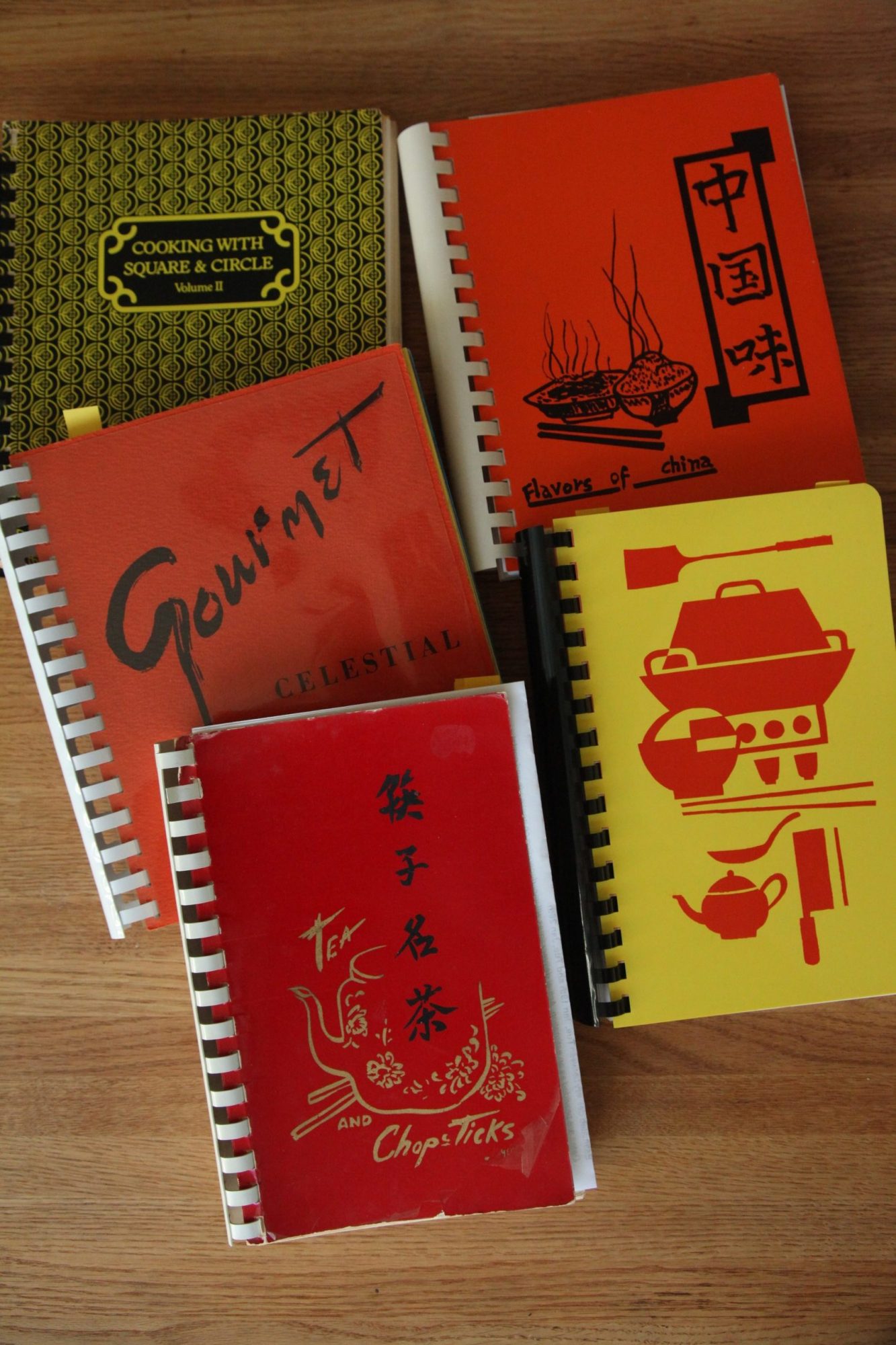

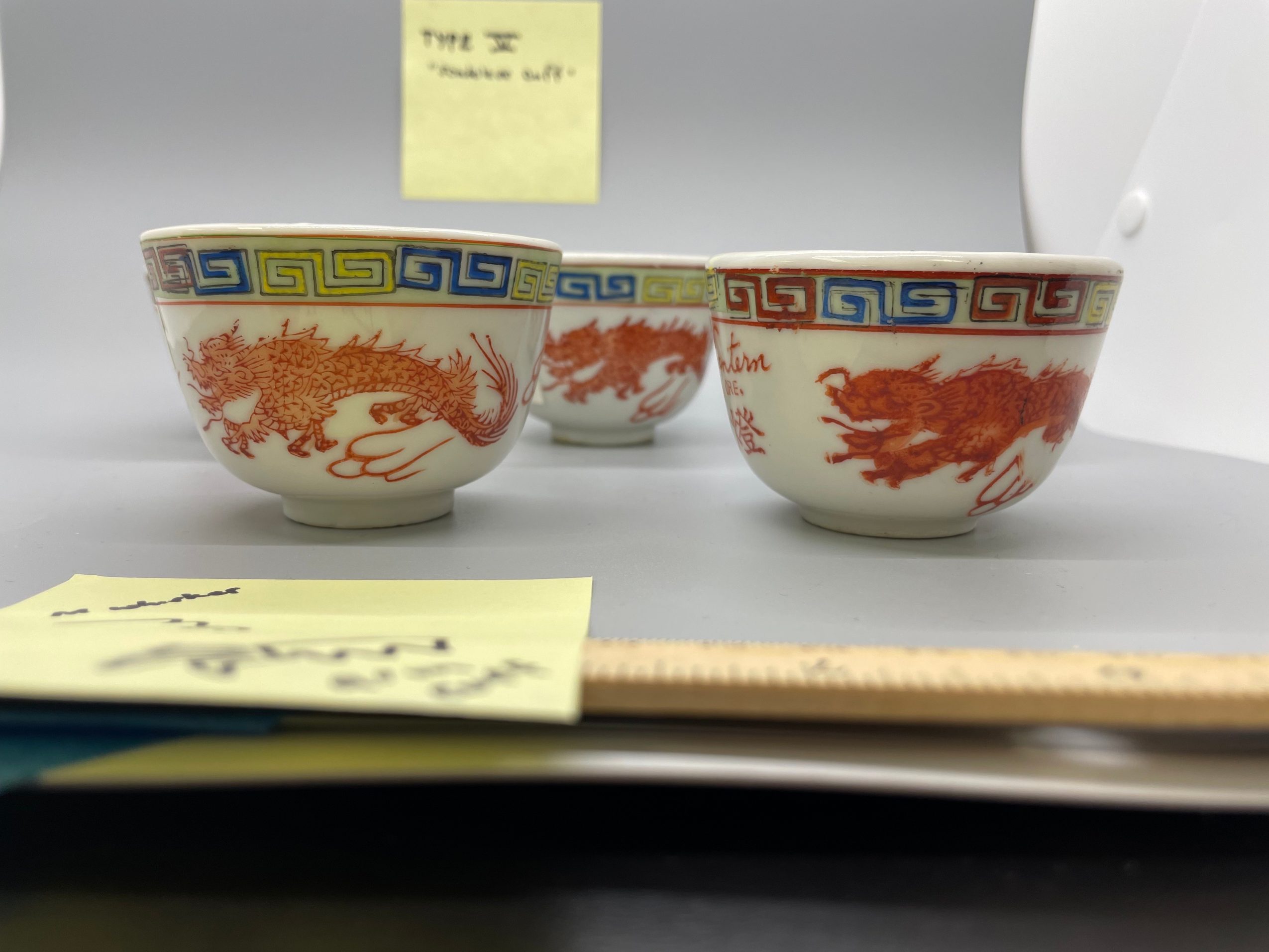

Two other projects, which are also in progress, focus on food and material culture – that is, all of the stuff we use in our everyday lives. In collaboration with Clement Lai, one of these projects uses Chinese American community cookbooks to examine Chinese American homestyle foodways. A lot of attention around Asian American food has focused on restaurants. I’m interested in looking at what those Chinese American chefs are eating in their own homes and the stories behind these foodways. In collaboration with Laurie Wilkie, the other project uses Chinese restaurant ceramics distributed by F. S. Louie to investigate diasporic networks connecting Chinese American restauranteurs across the country. Since learning more about Asian American Studies, I’ve been interested in thinking about connections between Chinese Americans, social, economic, familial, or otherwise. Through what otherwise seems like mundane pieces of material culture distributed by a single company, this project provides a glimpse into these complex networks that helped Chinese Americans survive and thrive in the United States.

These projects reflect my interdisciplinary training in Asian American Studies and archaeology. While it may seem like I’m not doing archaeological work today because I’m not excavating artifacts, my archaeological training is instrumental in shaping how I think about the world through the things we use daily. Those mundane, everyday activities that are otherwise dismissed as unimportant are the most important, fascinating parts of history for me. What are Asian Americans doing on a daily basis to survive but also thrive and build community through these everyday actions? What role does material culture play in this? I’m proud to have been a forerunner in this interdisciplinary perspective that brings a material culture-oriented perspective to Chinese American social histories and Ethnic Studies theory and knowledge to Chinese American historical archaeology.

Can you talk to us about how you think about risk?

Risk taker isn’t a characteristic I’d use to describe myself, but after reflecting on these questions and my responses, I guess I have taken risks to pursue the kind of work I wanted to do. These risks may not be on the same level as jumping out of an airplane, but I wouldn’t have been able to pave the way for my interdisciplinary approach to archaeology without taking a risk and believing that there was much to be gained at the intersection of Asian American Studies and Chinese American historical archaeologies. Pushing back against the status quo to change paradigms is risk-taking, and this is an important step for any discipline to evolve. Working on the margins of the academy as contingent faculty is risk-taking, but it has allowed me to continue teaching in Asian American Studies and inspiring the next generation. Personally, I know I wouldn’t have been able to do any of this work in a sustained way without a community of folks who understood the importance of this work and provided much-needed support.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://asianam.ucla.edu/person/kelly-fong/ https://www.aasc.ucla.edu/textbook/ https://chssc.org/five-chinatowns/

Image Credits

Kelly Fong

Clement Lai

Laurie Wilkie