Today we’d like to introduce you to Rie Lee.

Hi Rie, so excited to have you on the platform. So before we get into questions about your work-life, maybe you can bring our readers up to speed on your story and how you got to where you are today?

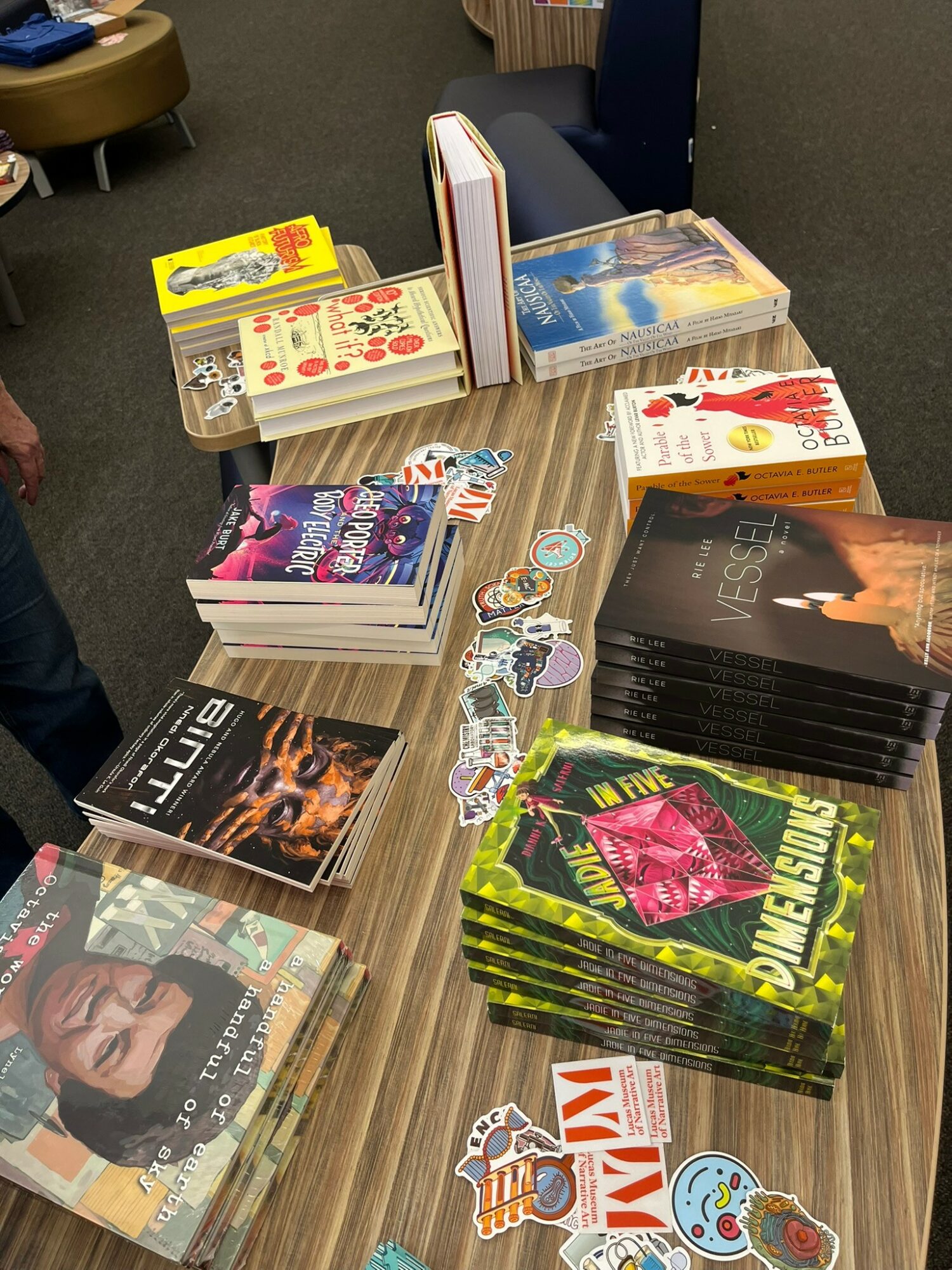

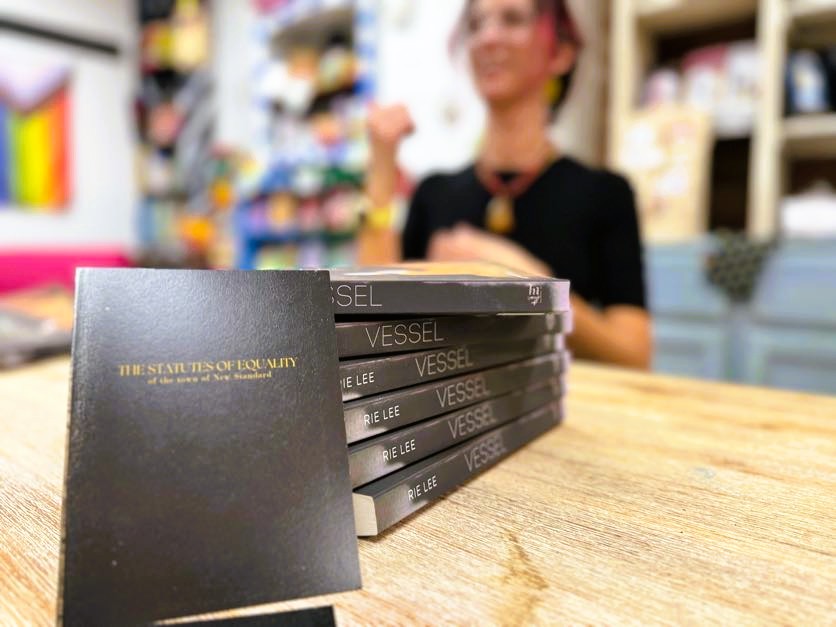

I started writing my first full-length novel in choir rehearsal when I was 11 years old. It was terrible. A dozen years later, I earned my MFA in Creative Writing from Eastern Washington University in 2014, where I gained indie publishing experience by serving as Managing Editor for Willow Springs literary magazine, and also wrote my second (significantly less-bad) novel, VESSEL, which was released in December with a kick-off in January, days before the Eaton Fire broke out, at the marvelous Underdog Bookstore in Monrovia. The book follows a true believer, Paige, and her journey out of her high-control religion.

True believers are people who have bought entirely into their belief system. These are the people who make excuses for all of the terrible things that people who are in their belief community do, because all of those terrible things are in service to the greater good. These are the people who believe so much in the greater good that they are willing to die for it.

I was that true believer, too. I grew up Baptist in Fresno, California. Fresno is an interesting place, and quite conservative for California. It’s a place with lots of local pride, where there’s a simultaneous sense of “we’re an awesome city in its own right, who needs those big-city jerks” and “let’s install world-class cultural institutions so that we’re comparable to Los Angeles.” It’s a relatively large city — 500,000 people during the aughts — with tons of insular communities. Fresno is more than 50% Hispanic/Latinx, and my insular community reflected this: my dad’s family is Mexican, my mom’s family is Spanish and French, and both of them were raised Catholic. I was raised immersed in my dad’s family, everyone of whom spoke fluent English, but who had strongly inherited Mexican-Catholic sensibilities. Basically, “Encanto” is my life. Minus the happy ending.

That environment did a number on me. I grew up with this idea drilled into me that I was a sinner, and that was just by default, and I had to confess how awful I was to Jesus in order to be saved from being burned for eternity when I died. And more than that, it was up to me to prevent my friends from that same fate, and if I didn’t, it would be my fault.

I was taught evangelical recruitment techniques: give the gentle sell, use the particular gifts God has given you to show how much you’re so happy that you have Jesus and God in your life, that you have been saved from being the scum you were born as, because as soon as you were born you sinned. You sinned with your impure thoughts that Jesus saw on a regular basis on a giant screen in Heaven at the pearly gates, judging you for whenever you got there, and you had to hope that your faith was good enough during your life on Earth, that you had asked to be saved enough times that you wouldn’t be rejected right then and there for that one time you masturbated in secret and didn’t ask for forgiveness.

Because that’s what religion was in my community: a lifetime of servitude to the Lord. A lifetime of knowing the right things to say, of giving platitudes for everything, of feeling obligated to share every compulsion I had (when I got my first kiss, I felt like I had to sit both of my parents down separately and admit it to them, guilt and delight warring equally for space in my brain). A lifetime of prioritizing work and family and putting friends and fun at the bottom of your list. And when combined with Latin culture, it meant no space for privacy. Total vulnerability. That was what faith meant.

Pleasure wasn’t part of that. It was something to hide.

VESSEL is fiction, but of course there’s that quote about all fiction just being nonfiction with the names changed, and — fine, okay, this falls under that adage. It’s the result of my own processing of my own coming-out and religious-deconstruction process, very much the story of a cult true believer in fiction. Paige is a character who is completely bought into this system she believes will be her salvation and can’t fathom other ways of being. She is willing to stuff parts of herself down so that the system can continue, believing that she and she alone is the thing that is wrong with it. There’s a strong element of self-gaslighting when you’re in a high-control environment like this — I would know. So much of that was my own upbringing. But I hope that readers can relate to Paige’s journey and find their own empowerment out of it.

Would you say it’s been a smooth road, and if not what are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced along the way?

Ha. No.

Deconstructing from religion is a terrifying experience. It’s traumatic in a lot of ways because there’s so much of your self that you have to reckon with — and ultimately part with.

When I was in youth group service at church in high school, I raised my hands during songs, moved by the power of what I thought was god. I surrendered myself to Jesus’s love. I surrendered myself to the will of a legendary being who allegedly created the existence of everything, and whose existence I can’t prove but I must trust at risk of losing my faith, a fate worse than death. Or abuse. Abuse is worth it—valuable, even—in the process of faith, because faith can get you anywhere. Faith can set you free.

Except for me, faith was the thing that chained me. I was accountable to it. Everything I did was in service of a faith I inherited from other people. It was a faith not just given to me, not offered, but mandated to me.

As Paris Paloma so succinctly put it, “it’s not an act of love if you make her.”

This teaching of surrender in Christianity may seem like a relief to some. It did for me, when I was younger. I wanted someone to take control over my life and give me peace, because I was fucking tired. I wanted to surrender to something, anything, that could make my pain better, whether that was Jesus or death or, hell, both.

Eventually I realised that Jesus wasn’t going to do shit, because it was all a setup. Some dude in the sky made a world I didn’t ask for, made me suffer in ways I didn’t ask for, and then had some ego trip telling me that he was the only one I should believe in, then made my ancestors provide blood atonement, then made it so I had to surrender my life to him? And he would somehow make it better? I was surrendering. I was surrendering as hard as I could, and I was still having panic attacks on a regular basis. I still wanted to die to escape it all, because I hadn’t signed up for any of it.

The thing about growing up that way—about being taught the importance of surrender as a means of survival, of being “saved,” rescued from a fate you were destined for without your consent—is that you learn to surrender yourself to other authorities in your life. Church leaders, teachers. Parents. And the surrender doesn’t actually save you. It just gives people control over you.

So I walked away. And it was terrifying, because with relinquishing my faith, I was then alone and without any coping mechanisms. To let go of faith is in itself an act of sheer faith—that you’re going to survive without the safety net you’ve been able to know is there your whole life. It’s trust in what you know: that that safety net has had holes in it this whole time, and that no matter how many times people tell you it’ll catch you, you know it won’t catch you. And when you have a new faith, and don’t have a community reinforcing it around you, it’s lonely and terrifying.

But in my case, it was also incredibly worth it. I have found so much healing over the years from walking away from my religion. I have recreated the foundation of my sense of belief, of how I see my existence in the world, and I am constantly learning more and shifting. But now I’ve built in the ability to shift into my foundation, and my sense of self is malleable to be able to handle when I’m unsure or wrong. What I’ve built on top of it is also a sense of surrender: to the knowledge that I don’t have all the answers yet, and that I likely never will, and that I will be wrong many, many times. I’ve found peace in knowing that there’s no such thing as purity, though I’m still trying to unlearn the impulse to clean all of my mistakes in a way that will render me blameless. Peace is now something that I have created for myself, and it isn’t something that someone else has created for me. It’s mine.

Appreciate you sharing that. What else should we know about what you do?

I’m a novelist. I’ve tried so hard not to be, but I just am. I got a whole graduate degree in fiction-writing where I was supposed to write short stories, and I couldn’t do it. Woe.

I specialize in speculative fiction–specifically, dystopias involving high-control environments (more commonly called “cults,” which is a judgmental term that everyone denies accusations of anyway). Most of my work–including my community work facilitating “voting study parties” (https://votingstudyparty.org) that aim to depolarize political conversations by bringing a tangible approach to local, down-ballot issues–has something to do with the concept of belief. I grew up a true believer, and I know what it’s like to be stigmatized for that, and how damaging that stigma is when you’re trying to figure a way out of the prison of others’ beliefs you’ve convinced yourself were your own.

We all have a different way of looking at and defining success. How do you define success?

I manage contracts by trade, so I suppose I take a particularly legal definition for a question like this. Success is defined as the completion of the work that was agreed upon to be performed, in that arena.

As I get older and I have more experiences, I think the concept of success has really shifted for me. I spend a lot of time establishing what my day is going to look like and call it a success if I get all of the tasks done that I put on my checklist. But more and more, I feel like success is really the ability to make it to another day to give your loved ones hugs and kisses, and minimizing the existential anxiety of existence while you’re at it.

Pricing:

- Paperback – $16.99

- ebook – $9.99

Contact Info:

- Website: https://riewrites.org/vessel

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/yesrielee/

- Other: https://votingstudyparty.org

Image Credits

Rie Lee, Adriana Redditt, Emily Doughty