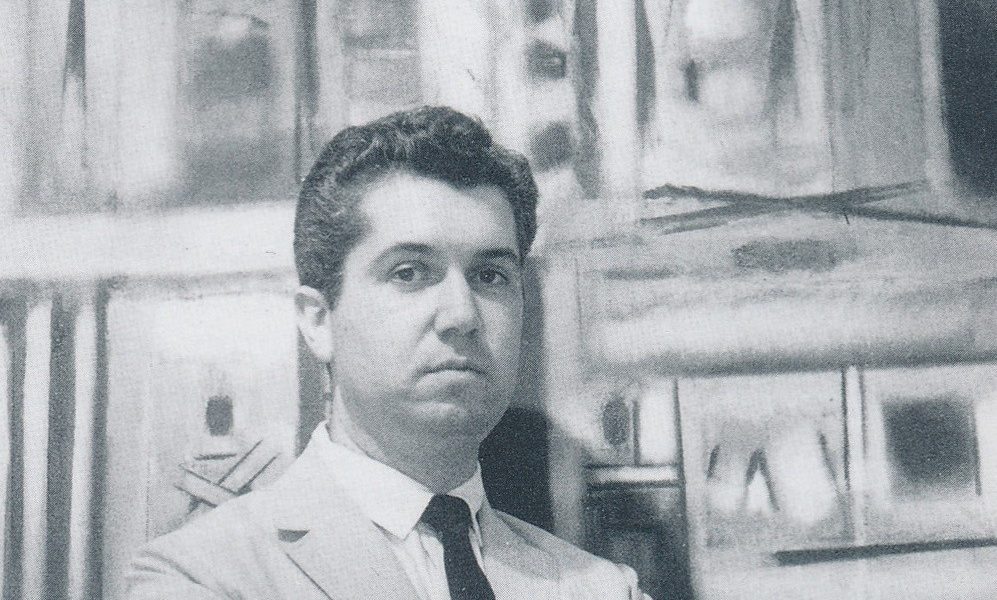

Today we’d like to introduce you to Walter Askin.

Hi Walter, so excited to have you with us today. What can you tell us about your story?

The Pasadena Art Museum was very important to my development as an artist probably even more important than the teachers at the City College. You could look at the Blue Four there (Galka Scheyer collection, which is Paul Klee, Feininger, Jawlensky, Kandinsky) and experience the different ways that they approached the process of visualization. That meant a lot to me as a student growing up. I could go there when I was in junior high school and look at things and sometimes a person like Vincent Price would be there. He’d come over and just talk with you and ask you about what you were doing and that was pretty exciting. The Pasadena Art Museum wasn’t an ordinary place, by any means. It was a very fine provincial museum. They would show the films of Fischinger, and one of my big thrills was much later on when he came and sat in my backyard after an opening at the museum, and we had a chance to truly talk because as a sixteen-year-old I was very much influenced by seeing those films, and I even made a short film myself. I took an Easter vacation, and I was totally undone by the fact that all my work for the whole week on Easter vacation, night and day, went by—pffft on the screen! You know, it was in no time at all.

The Pasadena library used to have lectures in the field of art. Man Ray gave a talk there and people attacked him because that was during a period when people saw communism lurking behind every bush. And of course, coming from France there were greater suspicions of communism. A lot of the students that passed thru City College were proto communists – they dropped that after a while but there was an interest in it at that time. So people during the talk were attacking him – a talk which he started out by citing the review of his show by the critic for the LA Times and refuting this criticism of his work step by step. The questions got fairly heated and he answered them as he walked down the center aisle of the auditorium. Finally, the last question came and Man Ray was no longer there…

Pasadena at that time was on a 6-4-4 plan. You had six years of elementary school, four years of junior high, and then you went to the city college, which was called junior college then, and you had the last two years of high school there plus the first two years of college. People tended to stay on there, because Pasadena City College had a very strong art program then, and I think continues to have a strong one now. But that’s where I ran into Wally Hedrick and David Simpson, Hayward King, Paula Clark-Samazan. She was known as Paula Webb then. The reason that we tended to cluster together is that we were at the school from 1945 until 1949, and that was a period when GIs were returning from the Pacific and European theater, and they felt that they had missed out. There was a burgeoning economy, and they felt they hadn’t been earning money during all that time that they were in the service so they were after gold. They were all going into commercial art, and they were going to make money at it. We hadn’t had that kind of background, and we had much more altruistic interests, and so we tended to focus on the fine arts. Our interest was in art as art rather than art as a means of producing an income. You have to realize at that time that you couldn’t earn your living, even a modest living, from doing art, fine art. If you wanted to make any money off of art, you had to go into advertising, design, or automobile design, and so forth. There was this idea very prevalent at that time, sort of a Bauhaus idea, that making chairs, interior design, and so forth, doing pots and all the rest of it, was equal to, had the density of content you’d find in paintings, drawings and sculpture, and that fine artists should be out decorating buildings with mosaics and sculpture and that sort of thing. Millard Sheets, who was in this area, very strongly emphasized that kind of idea, and you saw the results of that on the Home Savings and Loan buildings that he did all over the place.

Plus, Pasadena City College was funneling all of their students directly into Art Center School, which was over on Third Avenue then. And, of course, Art Center’s animation program fed people directly into the Disney Studios. If you went into automobile design, you got a job, if you were at the top of your class, at General Motors. And they were known for eliminating people who were not up to snuff, too. So there’s this strong sense of competitiveness there. Everybody we went to school with, you see, was five years older than we were. When we went down to sign up for classes, the counselor for the Art Department was always trying to push us into commercial design, and always making up these schedules for us, and we would have to go down and vociferously fight to remain in a fine arts-oriented program. I remember when a group of my compatriots went out to the San Francisco School of Fine Arts and were asked by the director, “Do you ever intend to make your living off your work?” They said no and were welcomed with “You’re in the right place.” So there was this sense.

The one thing I’m grateful about, though, for the experience I had at Berkeley, was there was a genuine belief in an innate ability of the human being to produce, create, manufacture ideas out of nothing, that you simply started to work, and in the process of working, came across the idea that you wouldn’t have come across if you made a conscious decision before you started.

Well, I think it was the idea that you can make a life around art, and that the most important aspect of art was its spiritual presence and the way it activated one psychically. The interest in psychology was very, very strong at that time and preceded a different kind of look at psychology that occurred later on in the sixties and seventies, so that we grew up in an atmosphere where there was an uncanny concern for what was not visible, you know, just making the invisible visible, which really was Klee’s major thesis. There was also something about the way artists lived their lives, of course, and we thrived on learning about those things.

And I think that’s why everyone except myself went to San Francisco Art Institute because that was really the ivory tower. I was more interested in going to a place where art was found in the context with other subjects. I also knew at that time that I was interested in teaching as a means of earning my living so that my art would be free from any kind of economic imperative or economic constraints.

I saw myself as wanting to be an artist but realized I couldn’t support myself by doing that and that I would need to find an alternative, and it seemed to me the best, most liberating way to do that was to teach art. I can remember going to the first painting class with Margaret Peterson O’Hagen, and Jay DeFeo was sitting right below me and Fred Reichman was over here. Everybody was in a very active frame of mind, and people like Walter Snelgrove were there. As a matter of fact, it was the years of the Walters. There was Walter Askin, Walter Snelgrove, Walter Wong, Walter Bach. I enjoyed taking classes with Alfred Frankenstein, and he was extremely good. But Horn’s class in medieval art really gave me a kind of understanding of what art history could mean.

My friends in this building on University Avenue used to invite David Park and Elmer Bishoff and the jazz group over to play on Saturday nights. So, one evening a crowd developed there, and they said, “Well, we need more room, so let’s take out this wall.” So they hammered out the plaster at the top and the bottom of the wall and sawed out the studs and threw the wall out in the back yard. Bill Morehouse, who lived up above, had a floor that started to be concave rather than flat. I came in the next day and I just knew I was going to jail because I had signed a lease saying I would not change the color of the walls without contacting the owners.

I’m sure you wouldn’t say it’s been obstacle free, but so far would you say the journey have been a fairly smooth road?

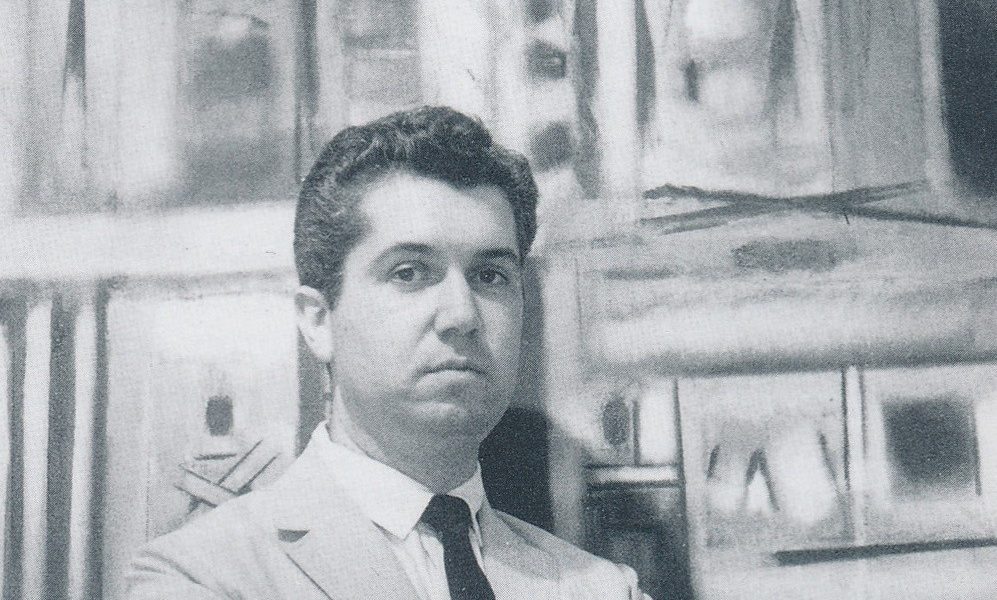

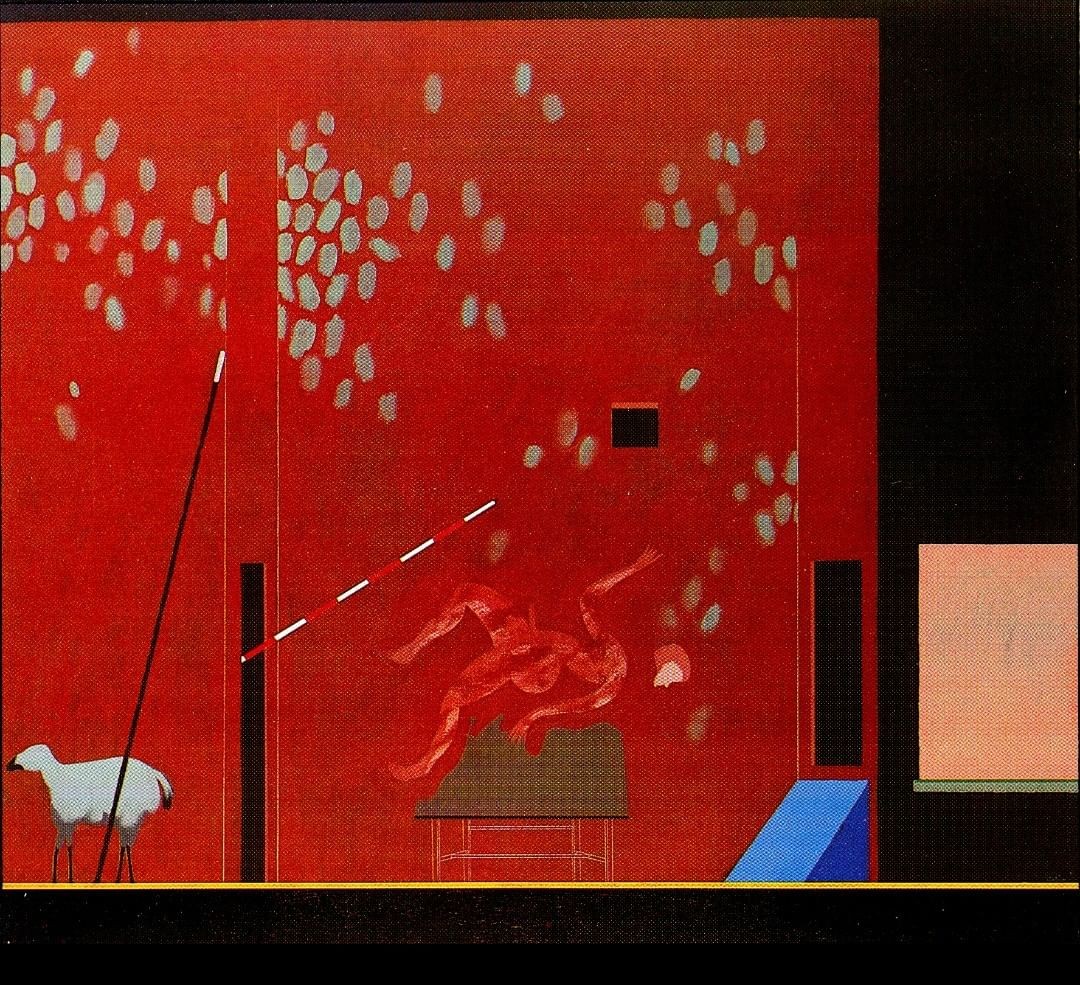

I’ve been influenced by a number of different historical art forms and one is Indian art – art from India. In reading about that I discovered that Brahman thought attempted to find a total conceptual enclosure for every aspect of existence – in other words, a microcosm that attempted to resolve the variety of existence rather than purify things. So within my works, I try to include those things that are profane with things that are sacred. Things that are clear with things that are unclear. Things that are humorous with things that are serious and so forth. So the whole thing is to bring together poles of existence and bring them together on a single plane rather than separating things from each other. One of the problems that people have in looking at my works is that they see some things that are very clear in there and yet when they try to get the overall gist of the piece they find that they’re on insubstantial ground. So a part of all this is the sense of mystery. So that the work continues to have a sense of play for the person who looks at the work and so there are all kinds of conjectures, all kinds of inflections, all sorts of associations that are put in there. I try to locate a very specific area of experience for the piece so that people aren’t just taking anything away from a work and yet the work remains somewhat subversive to ordinary systems of thought or the usual patterns of thought or mundane systems of thought. Hopefully, that will surprise people and awaken them out of habits. Awaken them out of their own private tapes and force them into another world. Most people don’t want to make that effort or most people find difficulty with that effort. They’ve been trained to read works of art in very clear ways particularly when they have narrative elements as mine do.

Appreciate you sharing that. What else should we know about what you do?

Like most artists, I keep thinking that I’m changing quite radically. When I look back and I don’t see as much change as I presume I’m about, on one hand I’m very pleased with that because there’s a certain kind of integrity that goes through it. If there’s one thing that I think is a keyword for me these days is that integrity but on the other hand, it also indicates how difficult it is for one to get outside of oneself to make a move in the process of becoming.

I grew up within the abstract expressionist movement and so underneath all these images is a concern for the primacy of form first of all and that form develops through a process which is open rather than closed. So even work which has very specific elements in it has a beginning where I don’t have any idea of what is going to happen there. The process of play permits me to put things in, take things out off, to follow the direction that the work of art establishes. I believe essentially in the ideas of freedom and liberation as a principle focus of work to escape somehow from the limitations of reality. To not feel trapped by our existence and so that means one has to open themselves up to all kinds of risks, chances… and games are very serious part of that. I think adults if they lose that sense of play have lost a very important part of of their existence. I take it to be the most serious, most spiritually orientated aspect of our existence. As a matter of fact, most other things in life don’t make any sense unless they’re somehow coordinated and put together by an act of play. We live in a world today where we’re faced with just a plethora of bizarre combinations of images of things that press in on us. I think it’s very hard for human beings to make any kind of sense out of those things and to give direction to one’s life. I think this process of play is where we put those things aside for a moment and only let them flood in as they’re called upon. We’re all large reservoirs of content and the big problem is to get that content out and to let it direct what we do rather than being directed by all these things that are around us.

So I regard my works principally as fake facts or true fictions. They have a basis in reality but they reflect on, off, other possibilities, other modes of action, other modes of behavior. I don’t try to assert that in my work. I don’t try to replicate myself in my work. I don’t try to have my work be self-expression but rather to be an antidote to my existence and hopefully with this process of creating things I become more like my work rather than my work of being a representation of me. To focus on ideas, extend oneself and enjoin in a process of becoming… My art has been a means of making the break toward another being but that process is a slow one. If one were to make a total break, then you would lose all that language that was so important and I think most of us need to bring along at least in our minds the entire history of art – a whole coterie of ideas that are found in literature – a sort of sense that come from music … and so forth… I think we need to recognize that we belong to a milieu. That were part of a culture. That we are not isolated. That we are not alone and then a part of what we do is, belongs to an act of giving… Making connections with other people as we make progress ourselves.

Can you talk to us about how you think about risk?

My background, my work is closely aligned with the abstract expressionist movement. I’ve always tried to teach my art class the way I create a work of art so there’s no fixed mode. I am an abstract expressionist – I come out of an abstract expressionist culture and that’s a place where you do not preconceive the work but you discover the idea of the work in the act of creating the work. So that’s the way I felt it was important to teach. That you just started to listen and look at what people were doing and follow the student as much as the student follows you. And then not to give a single response to the work in a single set of decisions that the students could make but to give them a number of different responses and then they have to make a decision. There’s always a tendency particularly when you’re in a classroom with your peers to want to do things that really look good. And if you do that you tend to replicate your mastery. There are certain things you’re good at but sometimes you need to delve out into far distant reaches – not to keep repeating that mastery. Take chances, venture out, test possibilities – because the visual arts are a language. I’ve done sculpture – steel sculpture, bronze cast sculpture, wood sculpture… paintings in acrylic and watercolor and oil … prints in lithography and intaglio and I didn’t do those things willy-nilly but because different ideas can be said more succinctly and clearly in a different medium. The media in a way is a response to the ideas you develop as you’re moving along.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-walter-askin-13013#transcript

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/walteraskin/?hl=en

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/WalterAskin?ref_src=twsrc%5Egoogle%7Ctwcamp%5Eserp%7Ctwgr%5Eauthor

- Youtube: https://youtu.be/LKeC3JoxJ8E?t=195

- Other: https://walteraskin.net

, https://walteraskin.art

Image Credit:

Art works copyright Walter Askin