We’re looking forward to introducing you to Douglas Weissman. Check out our conversation below.

Hi Douglas, thank you so much for taking time out of your busy day to share your story, experiences and insights with our readers. Let’s jump right in with an interesting one: What do the first 90 minutes of your day look like?

My alarm goes off at 5:05 AM—and yes, that’s intentionally five minutes past the hour. I originally thought that being just outside of the predictable 5:00 AM would somehow make it easier to get up, but after 14 years of waking up between 4:30 and 5:15, my body has adapted to the point where it’s actually harder NOT to wake up at that time, even when I’m exhausted.

My routine is pretty consistent six days a week: I floss, brush my teeth, write down three things I’m grateful for, and then exercise, either at home or at the nearby gym. It might sound rigid, but I’ve learned that this sequence works. The gratitude practice creates a nice mental bridge between the automatic morning tasks and the energizing physical activity.

Interestingly, when I break from this routine on Saturdays when I want to take advantage of sleeping in, I end up more groggy and grumpy throughout the day. My body has essentially trained itself to expect this structure, and deviating from it actually makes me feel worse. It’s become less about discipline and more about listening to what my body and mind need to function best.

Can you briefly introduce yourself and share what makes you or your brand unique?

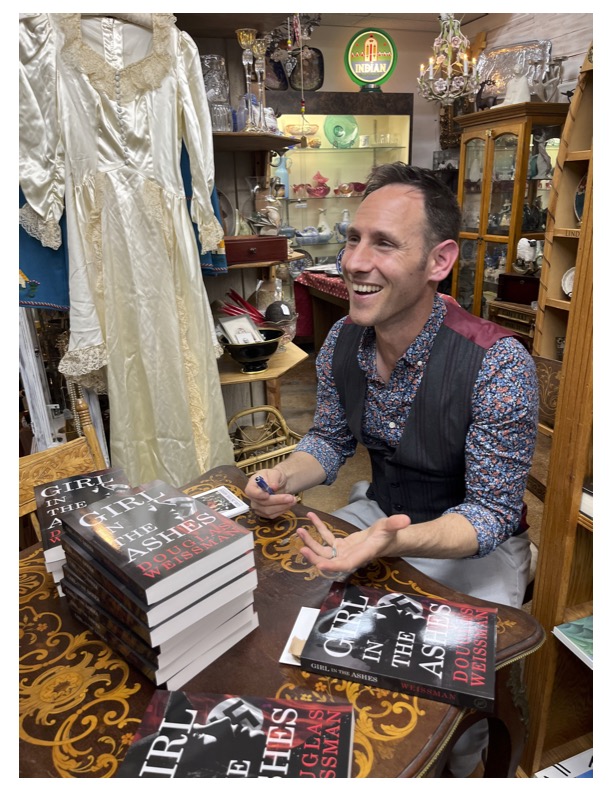

My name is Douglas Weissman, and I’m a novelist, travel writer, screenwriter, and creative strategist. If it involves storytelling and creativity, I want to be part of it—whether that’s building a narrative around an in-person themed party or creating the emotional arc for a character in a comic book. My goal is always the same: create something that takes the audience on an emotional ride and makes them feel something.

I grew up in the San Fernando Valley—that corner of Los Angeles where we talk fast, say “like” a lot, and enjoyed the suburban life of the big city. After college, I caught the travel bug hard during a year abroad in Florence, Italy. Perfect timing, really, since it was the height of the Great Recession and no jobs were waiting for me anyway. So I booked it west and kept going for nearly a year until I made it back to US ground.

But one year later, after hustling at restaurants and even selling timeshares, I couldn’t take it anymore and ran again—this time to South America for nearly six months, traveling from Colombia down to Argentina, then spending six weeks backpacking through Mexico. During that journey, I got accepted to grad school at the University of San Francisco for an MFA in Creative Writing, where I used my travel experiences to inform my first completed novel. That labor of love led to seven more novels on contract after graduation.

I’ve traveled through Southern and East Africa, always finding inspiration in authentic connections with people I meet and the captivating stories I hear along the way. My professional career has been about collecting, sharing, and telling stories across every medium—novels, travel essays, travel guides, screenplays, even brand narratives.

Right now, I’m working on a YA novel about climate positivity, exploring how any action, no matter how small, makes a difference. It’s all about finding hope and agency in our biggest challenges.

Okay, so here’s a deep one: What did you believe about yourself as a child that you no longer believe?

That failure meant I wasn’t cut out for something.

As a child, I believed talent was binary. You either had it or you didn’t. If I struggled with math, I wasn’t a “math person.” If my first short story got rejected, I wasn’t meant to be a writer. This fixed mindset dominated my childhood thinking, and honestly, it wasn’t challenged much in school either. We didn’t talk about growth mindset back then.

I thought my natural abilities had already been determined, like some cosmic lottery I’d either won or lost. When things got difficult, I interpreted that difficulty as a sign to quit rather than a signal to persist. I believed successful people had discovered their one true calling early and sailed smoothly toward it. I was convinced if I didn’t know the career I wanted by 17, I’d be messed up for life.

Adulthood completely shattered this belief. My year selling timeshares became crucial research for understanding human psychology and persuasion, even if I hated the application. Those months waiting tables taught me about service, reading people, and working under pressure.

I discovered that struggle is the pathway to developing skill. My travel experiences work their way into my novels because I practiced noticing details, conversations, and cultural nuances until it became second nature. Every rejection letter made me a better writer by forcing me to examine what wasn’t working. I also lean on the fact, I was definitely not the most talented writer in my program. There were so many better writers, but I stuck with it and got published while others didn’t.

Now I actively seek out challenges that make me uncomfortable because I know that discomfort signals growth. Adult me recognizes it as proof that curiosity and persistence matter most.

What fear has held you back the most in your life?

Fear of rejection. Marty McFly captured it perfectly when he said, “What if I send in the tape and they don’t like it? I mean, what if they say I’m no good? What if they say, ‘Get outta here, kid, you got no future.’ I mean, I just don’t think I can take that kind of rejection.”

That’s exactly how I felt for years. This fear stopped me from doing countless things when I was younger and continued well into adulthood. The worst part wasn’t just avoiding opportunities altogether. It was the self-sabotage that came with it. I’d deliberately not put my best effort into certain opportunities because I told myself that if I didn’t really try, I’d know exactly why I got rejected. It was a twisted form of control. If I gave something my all and still got rejected, that felt like a judgment on my actual worth rather than just my effort level.

Looking back, I can see how this played out in my early writing submissions. I’d send out pieces I knew weren’t quite ready, almost guaranteeing the rejection. That way, I could tell myself the rejection was about the unfinished work, not about my potential as a writer. It was easier to live with “I didn’t try hard enough” than “I tried my best and it still wasn’t good enough.”

This fear kept me from pursuing certain travel writing assignments, from pitching bigger publications, from taking creative risks in my novels. I was so afraid of hearing “no” that I’d engineer situations where the “no” felt less personal.

The irony is that rejection became my teacher once I finally started putting myself fully out there. Each real rejection, the kind that came after genuine effort, taught me something valuable about my craft, my market, or my approach. Fear of rejection had been protecting me from exactly the feedback I needed to grow. It still bubbles up but it’s less aggressive than it was in the past.

Alright, so if you are open to it, let’s explore some philosophical questions that touch on your values and worldview. Where are smart people getting it totally wrong today?

Alright, so if you are open to it, let’s explore some philosophical questions that touch on your values and worldview. Where are smart people getting it totally wrong today?

Smart people are getting it wrong by thinking that all smart people are smart about everything. Most people can be really smart about one or two things, and they’re incredible in those spaces, but then we assume that because they’re so knowledgeable there, they must be equally smart everywhere else.

I turn this on myself often enough. I’m a great storyteller. I know I have the ability to dissect writing, provide feedback, look at nuance, and shape a story into something different easily. That doesn’t mean I can calculate someone’s mortgage payoff timeline within six months if they give me their financial details, or figure out pi to its tenth decimal place.

But we live in a culture that treats expertise as transferable. A brilliant tech entrepreneur suddenly becomes a trusted voice on public health policy. A gifted novelist starts weighing in on economic theory with the same confidence they bring to character development. Social media amplifies this because platforms reward confident takes regardless of actual expertise.

The problem isn’t that smart people have opinions outside their wheelhouse. It’s that they often don’t recognize the boundaries of their knowledge, and we don’t expect them to. We’ve created this myth of the Renaissance genius who can master everything, when in reality, true expertise requires such deep focus that it naturally limits breadth.

I’m still learning to catch myself when I start speaking with authority about subjects where I’m actually just an interested amateur. It just reinforces in my mind the power of the Dunning-Kruger Effect, which is clearly one of my favorite cognitive biases.

The smartest thing smart people can do is get comfortable saying “I don’t know” or “That’s outside my expertise.” But our culture interprets intellectual humility as weakness rather than wisdom.

We’d all be better served if we stopped expecting our experts to be universal and started appreciating the depth that comes from focused mastery.

Okay, so before we go, let’s tackle one more area. Are you doing what you were born to do—or what you were told to do?

On the other hand, I use my time between capitalistic marketing gigs to write novels and screenplays that explore family, connection, emotional truth, and who a person really is when they strip away all the elements society told them were required. The irony is that I’m actually really good at what I do because whether I’m in my day job or my night job, I’m still telling stories. The skills transfer completely.

By the time I figured out I could tell stories as a career without ending up penniless in a dive bar drinking myself to death and hoping they don’t close my tab, I wasn’t really listening to what I was told to do anyway. I’d already gone off script with all that travel, those random jobs, the unconventional path through multiple countries and experiences most people thought were irresponsible detours.

So maybe the answer is both. I found a way to do what I was born to do within the system I was told to participate in. I’m not completely free from societal expectations, but I’m not completely enslaved by them either. I’ve created this hybrid existence where I can pay my bills and fund my Starbucks habit while still pursuing the work that actually matters to me.

At the risk of sounding contrived, pedantic, and smug, maybe the real victory isn’t escaping the system entirely but learning how to use it to support what you’re actually here to do.

Contact Info:

- Website: http://douglasweissman.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/douglasweissman/

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/douglas-weissman/

Image Credits

Douglas Weissman