Today we’d like to introduce you to Mariela Garcia-Alvarado.

Hi Mariela, we’d love for you to start by introducing yourself.

I never know how to answer these questions. Too many times, the reaction has been, “Well, that was a lot,” “TMI,” or my favorite—“Some of this has to be made up.” I try to be open, but like most Latine households, I am bound to the saying: “La ropa sucia se lava en casa.” Your dirty laundry stays at home. Yet, my story is tangled in so many others—my identity stitched together from the best and worst moments of those who shaped me.

I grew up in the barrios of Santa Ana, California, where survival felt like a daily test but where the streets overflowed with people and stories of resilience, love, and humor. My dad was Mexican, my mom Guatemalan, and I was raised alongside my four sisters. From an early age, my mother drilled into us that our only job was to be good students—yet we were always expected to help run the family businesses. My two oldest sisters carried the heaviest burden, waking up at dawn to prep food, staying late to clean, ensuring the weight never crushed the rest of us. Even after my dad’s addiction forced us to shut the businesses down, my sisters still took on more than they should have. They covered my chores, shielded me from stress, even took beatings meant for me—so I could focus on school (I joined Model-UN after one of my sisters dropped to let me do it because the fees for each tournament were too much for my family , and the my other had me in AP classes and reading all her books so I knew them-maybe she knew them-before I was in the class).

I always loved to write, but my writing got me into trouble. I tried journaling, but one of my sisters read an entry and warned me that my parents would beat me if they found out I was leaving a paper trail. I tried fiction, but when my teacher mistook my writing for a confession of abuse, it led to an investigation that nearly got me disowned (they weren’t entirely wrong but I was exposing my family to ridicule). No one knew the whole story, but everyone had something to say about me. I wasn’t a perfect student before that incident, but after it, I started ditching school. I didn’t know how to make friends, keep friends, or be around people without assuming they were talking about me. A guy I dated said he was warned I was a “train wreck” because of my family history. I couldn’t focus in class, so I would ditch school to be at Barnes & Noble, do my homework, and read books I couldn’t afford. Despite my best efforts to send homework through my classmates, show up for tests, or special projects (like debates!), my ditching caught up to me. I went to my safe school, CSU-Fullerton. Creator, ancestors, and Diosito had a plan to send me there though, because it was my biggest blessing.

At CSUF, I had professors who introduced me to Paulo Freire, Augusto Boal, Gloria Anzaldúa, Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Judith Butler, and Frantz Fanon. But it was the college policy debate that taught me how to use their work to inspire my own. Debate saved me. I stumbled into the CSUF policy debate team and found performance artists disguised as debaters, kritik scholars pushing ideas beyond their breaking point. I was supposed to prepare for law school, but instead, I found something greater—a community that let me question, build, and remake myself. Luis M. Andrade, Romin Rajan, Ashley Moore, LaToya Greene, Deven E. Cooper—they didn’t just coach me, they saw me. And the BIPOC and queer debate community? They handed me a mic and I filled the silence with MY truth, MY stories…ME, all the pieces of me. Debate was more than a mental challenge, or game, it became a movement, one that pushed me to want to bring it back to Santa Ana. Fortunately, I wasn’t the only person wanting to share this activity with others. In my search to bring it back to Santa Ana, I was able to learn how to coach under one of the best speech and debate directors, Salvador Tinajero. Not only did we bring it to Santa Ana, our company has now been able to spread it all over Orange County and Los Angeles, San Jose, and now Peoria, Illinois. Debate gave me my voice. Now, I pass that privilege to my students as their speech and debate executive director.

I tell my students that breaking out of poverty is more than just making enough money to be comfortable. It requires making choices—sometimes impossible ones—that prevent trauma and heal wounds. It’s going to the doctor for preventative care, changing your diet, and exercising so that you don’t end up with open sores from diabetes or multiple strokes from high blood pressure, like so many in our neighborhood, including my dad. It’s looking at the father you lost to addiction long before diabetes took over, inspecting your own coping mechanisms, and choosing not to drown the way he did. It’s seeing your mother, strong but shattered, her rage a shield, her love a war zone—and deciding to heal instead of inherit. It’s getting therapy because you feel like you’re wearing the dirty laundry every single day. It’s rewiring a mind built for survival to trust that sometimes, the waves are calm. Yes, some things are out of our control and structural injustices will occur, but if you build strong networks and communities of people that will fight with you, you won’t be fighting poverty alone. But what do you do with all the pain? How do we process our own fragility?

Writer, artist, and healer Ehime Ora says, “Your body is not a coffin for pain to be buried in. Put it somewhere else.” My writing was never a cry for help; it was always a way to create new possibilities, to travel to different worlds. Now, I get to show my students how storytelling, poetry, theater, and writing can be tools to scratch whatever itch lingers in their minds. Because pain is not meant to be buried—it is meant to be transformed. My parents were more than just survivors. They were brilliant in ways the world never let them prove. They had the kind of intelligence that could have built empires if only they had been given the chance. But life never handed them chances, only struggles. And maybe that’s why I fight so hard now. Despite the pain, despite the sacrifices, despite the loneliness of social mobility or the uncertainty of the future, it is okay to take time to better YOURSELF. That’s why I teach, why I fight for my students’ voices, why I refuse to let our stories disappear into silence. Because our bodies are not coffins. Our voices are the echoes of survival—turning pain into art, wounds into wisdom, and struggle into something worth telling.

My father’s love was buried beneath the weight of his vices. We lost him in December 2024 to a series of heart attacks—a fatal mix of untreated diabetes, high blood pressure, and the demons he never fully let go of. And my mother, desperate to hold us together, used her rage like armor, a force meant to keep us safe, to keep my dad alive. Some days, she was the strongest person I knew, a woman who had escaped Guatemala as a refugee and built a life from nothing. Other days, she was the reason I flinched, the reason I bled. I love her deeply, admire her like no other, but I also know that guilt manifests in ways that hurt people. These days I use my background, my knowledge, and my love for reading, writing, and theater as tools to help me coach my students to tell their stories. Not all of them are itching to tell the world about their trauma, some of them want to entertain people through comedy, others want to share information they just learned, a few are there to find a safe space, to find friends that also challenge themselves academically, and many of them just want to prove to themselves that they are intelligent, despite whatever behavioral problem they may be trying to overcome.

My students keep me busy enough that my mom processes my absence as a good deed rather than a boundary–I will take the win. My sisters, they still protect me from knowing everything that goes on, though now it’s to ensure my students get a version of me that isn’t broken by the cycles of poverty that still haunt my family. My husband, who was my former debate partner, and I get to do this work together with students from all walks of life in the Midwest. So many of my closest friends were part of this activity too! I am so blessed to be part of a community of artists, scholars, and advocates that challenge themselves day in and day out; but my biggest blessing is finding a way to make this a career!

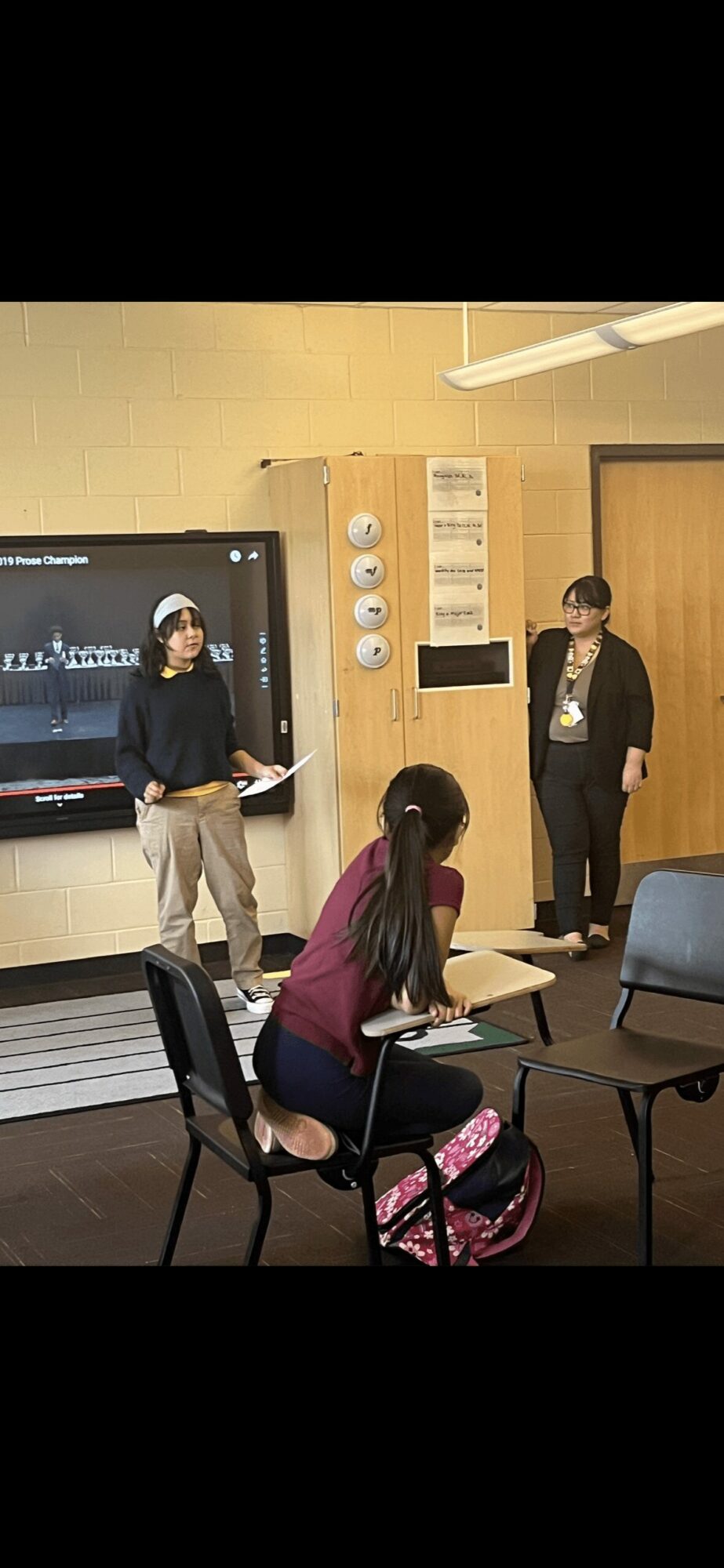

Before I left college, one of my professors told a class that wasn’t fully engaged that after graduation, you won’t be asked to share too many of your ideas. My debate coaches used to tell me, “You have 10 minutes where everyone has to listen to you, so what are you going to say?”. I now tell my students, “During school hours, and in so many other spaces, you will be told to be quiet. Here, I am telling you to speak up, as loud as you can, so take your chance to perform something unapologetically and without concern of what people will think. There will always be a person judging in the room, just like a speech and debate round, but they cannot take that moment away from you where everyone has to sit silently and listen to what you have to say. So, whatever you want to say, whatever you want to make them feel, you have 5-10 minutes.”

Can you talk to us a bit about the challenges and lessons you’ve learned along the way. Looking back would you say it’s been easy or smooth in retrospect?

I love pouring myself into my work, but it comes at a cost. I moved away from my family and friends to do what I love here in Illinois, and in doing so, I’ve missed out on a lot: birthdays, holidays, shows, family gatherings, even my own anniversary with Raul…

I’ve lived by the saying, “Be the person you needed when you were young and hurting,” but sometimes that means I don’t take the time to take care of myself. I still haven’t fully processed my dad’s death—or the fact that we buried him on my birthday. I don’t know what to do with all the memories, or what lessons I should be learning from losing him to the same unhealthy habits I haven’t been quick to change in myself.

I still people-please and love-bomb to a fault. I am either a puppy or a grown cat with people, and sometimes because of the rage I inherited, I am either completely submissive like a sloth because I cannot move fast enough to give an honest, raw reaction or brash like honey badger because I felt threatened (or, I just saw someone do something so ugly that I just couldn’t hold them through it but the love never went away–maybe it’s shock). I wish I had cared for some of my friendships more honestly, more patiently.

Sometimes, when I close my eyes, the painful memories still find their way through, especially when I am not distracted. I hate those moments. Maybe that is why I stay busy, I can’t have a random memory seep through. It’s likely why I keep having a lot of writer’s block or moments of disassociation, but who really knows…I am not always doing the work I preach.

My biggest struggle is keeping some of me in the shadows. I am terrified of what I might write, what might slip out of my mouth if I let my guard down too much. I feel this need to be calculated, to stitch myself together so neatly that no one will see the seams fraying underneath. There are things I don’t want to say out loud, memories I don’t want to give space to beyond my own mind. But sometimes they spill out anyway. And then comes the reaction I’ve grown so used to—”Oh. That’s a lot.” That’s when I retreat because I feel like a freak.

But I’m writing a lot these days. Collecting books, videos—expressions of grief, of healing, of closure. I’m curating a library of these things, building something tangible out of all the emotions I haven’t figured out how to fully process. Maybe one day, I’ll tell my story. Maybe one day, I’ll share it with my children. Not in a way that centers me, but in a way that lets them understand where they come from—without having to carry all of the weight of where I’ve been.

Thanks – so what else should our readers know about your work and what you’re currently focused on?

Most of my art exists in moments that were never captured on video—debate rounds that came and went, performances that lived only in the memories of whoever was in the room, or words/ideas scribbled in unpublished journal entries. One of my most cherished memories with my debate partner, Oscar Rosa—who tragically passed away during the COVID-19 pandemic. We performed the works of Sandra Cisneros, Gloria Anzaldúa, and other writers, using our voices and bodies to illustrate how indigenous peoples syncretized their goddesses—Tonantzin, Coatlicue—with the Virgen de Guadalupe as a mechanism of survival against theopolitical structures that sought to erase non-Western knowledge systems.

Oscar would throw me to the ground, drape a white sheet over me, shackle my wrists with a rosary, and simulate the violent force that coerced our ancestors into adopting Christianity. I know how controversial this performance was—and still is—but it was never about shock value. It was about truth. It was about using performance to make the brutality of epistemicide—the systematic erasure of indigenous knowledge—impossible to ignore. If this part of my story is cut or edited, I understand, but I also know that the work we did in those rounds meant something. It left an impact that no amount of academic citations could replicate. And when debaters refused to acknowledge our argument or we knew we had a judge in the round that was against performance debate methods, we would wear mirror masks to ensure that the people that came in, unwilling to listen to our form of argumentation, would have to face their performance of dismissal.

I have always been drawn to the radical potential of performance. I am heavily influenced by Theater of the Oppressed and Teatro Campesino because these methods transformed debate for me. They turned my rounds into something accessible—something that anyone, regardless of background, could walk into and understand. One of my earliest inspirations was learning how the Delano Grape Strike used performance as protest: farmworkers performed short skits on flatbed trucks and in union halls to dramatize their struggles. Pamphlets wouldn’t have worked—many workers couldn’t read, and they didn’t all speak the same language. But theater? Everyone understands a story. Everyone understands conflict. And so, performance became their most powerful tool for solidarity.

That’s what I wanted to bring into debate. Policy, law, and academia are often so exclusive, so elitist, that they alienate the very people they claim to advocate for. I never wanted to water down my arguments, but I also refused to make my advocacy incomprehensible to anyone outside the ivory tower. So, I performed. I used skits, poems, and movement to make sure that anyone who walked into my round—whether a judge, a competitor, or an uninitiated observer—could feel what I was arguing, not just hear it.

But the art I am most proud of isn’t my own. It’s the art I create with my students. Together, we take literature—sometimes existing works, sometimes original pieces, depending on the category—and transform it into something living, breathing, and meaningful. We build performances that don’t just entertain, but resonate. Our goal isn’t applause; it’s impact.

As a speech and debate director, I am a visionary. I don’t just consume media—I curate it. I build a library of voices, perspectives, and stories that my students can use to find their own. I help them discover literature that allows them to express truths they might not be ready to say outright, crafting performances that tell their stories without forcing them to be the main character. My job isn’t just about competition—it’s about giving students the tools to communicate, to advocate, to matter.

Beyond that, I help them shape the intangible: the way they move their bodies to communicate emotion, the way a glance at the right moment can shift the weight of a scene, the way a whisper can hold just as much power as a yell. Every pause, every breath, every choice they make on stage is a brushstroke in the masterpiece they are creating. And in those moments, they aren’t just students.

I am not just a coach. They aren’t just competitors. We are artists, turning words into impact, crafting something ephemeral yet unforgettable. Someone will remember what we made them feel, someone out there maybe needed to hear our message, maybe someone didn’t have the privilege to tell their story…regardless of the reason, we are telling stories to bridge communities as best as we can.

What matters most to you? Why?

LITERACY!

Sure, we can communicate with one another through various languages, sounds, non-verbal body language movements, etc…but to be able to read means your writing will transform beyond the depths of your mind. It means you can travel to worlds that existed in someone’s mind and body. Literacy is the building block to have ego-deaths, where someone’s writing was so perfectly crafted against a potentially harmful belief you had OR where you experienced something so new, that your brain had to create space for your neuroplasticity to adapt. It’s the difference between knowing the fine print in a system that wasn’t built to guide you and finding a way out through other people’s ideas. It’s having a tool of empowerment that literally no one could ever take away from you, no matter how much they tried. It’s a way out of your own mind…of poverty, of silence, of loneliness.

It’s a way to find community with voices before you, younger than you, and even your own. It how a kid can make a friend from similar interests. It’s how kids of limited-English or non-English speakers can help their parents with legal, medical, or information that isn’t translated. It’s being able to read warning labels, identifying lies, or even surviving erasure. It’s being able to text a friend without only using emojis, reading between the lines, or staying informed to be more compassionate.

What we don’t read, we might forget. What we don’t write, we may lose forever. Why do you think that so many oppressive narratives, fiction or non-fiction, try to prevent people from literacy or ban books. It’s because the moment someone learns to read, they cannot control what you will write or think.

Pricing:

- Varies, depends on the contract a district or school wants for services

- $100 for private speech and debate coaching

- $60 for professional development or leadership coaching

- $50 for tutoring

- $45 an hour for script work

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.advantagespeechanddebate.org/

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLJNwtH2svA4npXZ_I-lXPsrKdWWdeMEsn