Today we’d like to introduce you to Father Armenag (David) Bedrossian.

Hi Father Armenag (David), please kick things off for us with an introduction to yourself and your story.

My story is deeply rooted in the immigrant and refugee experience. I was born in Syria and raised in a region where faith, survival, and identity were inseparable. Growing up amid political instability and, later, the devastation of war, I witnessed firsthand what it means to lose home, safety, and certainty overnight. Those early experiences shaped my understanding of trauma, displacement, and resilience long before I had language for them.

I initially studied law, believing justice was the way to serve suffering communities. Over time, however, I felt called to a more personal form of accompaniment—one that walks with people not only through legal or social systems, but through grief, fear, and spiritual crisis. That calling led me to theological studies and eventually to the priesthood in the Armenian Catholic Church, where I took the name Father Armenag Bedrossian.

My ministry began in the Middle East, serving communities impacted by violence and loss. When I later immigrated to the United States and settled in Los Angeles, I found myself serving people whose stories mirrored my own—refugees fleeing war, families navigating cultural transition, and young people carrying unspoken trauma. Los Angeles became not just a place of ministry, but a living classroom of human suffering and hope.

Much of my work has centered on chaplaincy and trauma-informed spiritual care. I have stood with families after sudden deaths, accompanied individuals in moments of deep crisis, and offered pastoral care in hospitals, streets, courtrooms, and community spaces. I am especially drawn to moments when words fail—when presence, listening, and compassion become the most sacred forms of ministry.

Youth mentorship has also become a central part of my mission. Many young people—particularly children of immigrants—struggle with identity, pressure, grief, and expectations they rarely name. Walking with them, mentoring them, and helping them discover their worth and voice has been one of the most meaningful aspects of my journey.

Today, my work continues at the intersection of faith, trauma healing, and community rebuilding. I do not see my story as one of titles or positions, but of crossing borders—geographical, emotional, and spiritual—to remind people that they are not alone. My life’s work is rooted in one conviction: healing begins when someone is willing to stay, listen, and walk with you through the hardest chapters of your life.

Here are also some articles and documentaries about me and the mission I am involved with:

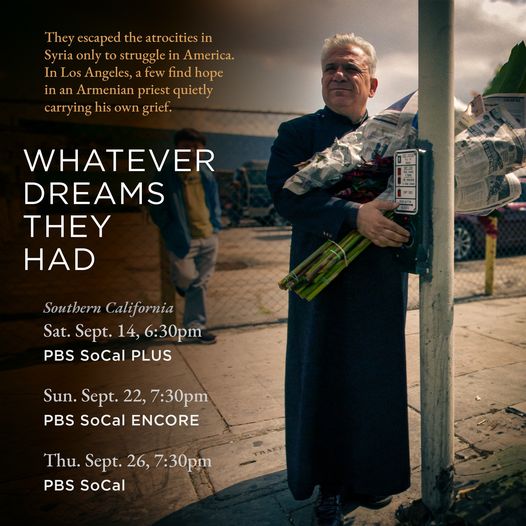

1- Whatever Dream they had. A special documentary on PBS TV

https://www.pbs.org/video/whatever-dreams-they-had-4r8cmg/

2- https://whatwillbecomeofus.com/ndbu

3- Armenian church in Boyle Heights sees a post-pandemic revival: ‘It’s our home.:

https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2021-05-23/armenian-church-post-covid-revival-boyle-heights

4- LA’s Armenian Catholics offer support, sacrifice amid wildfires, says pastor

https://angelusnews.com/local/la-catholics/la-fires-armenian-catholics/

5- Armenian church in Boyle Heights sees a post-pandemic revival: ‘It’s our home.’

https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2021-05-23/armenian-church-post-covid-revival-boyle-heights

Can you talk to us a bit about the challenges and lessons you’ve learned along the way. Looking back would you say it’s been easy or smooth in retrospect?

It has not been a smooth road—and I wouldn’t trust it if it had been. My journey has been shaped by disruption, loss, and constant rebuilding. Growing up in the Middle East and later living through war meant learning early how quickly stability can disappear. Immigration itself is a form of rupture—leaving behind language, culture, familiarity, and starting over while carrying invisible grief.

One of the deepest struggles has been bearing the weight of other people’s pain while learning how to carry my own. As a priest and chaplain, you are often called in at the worst moments—sudden deaths, violent loss, family breakdowns, trauma that has no easy answers. Over time, I had to learn that being strong for others does not mean being unbreakable. Learning healthy boundaries, emotional honesty, and self-care was not automatic; it was earned through exhaustion, failure, and reflection.

There were also challenges unique to serving immigrant and refugee communities—navigating limited resources, systemic barriers, and the feeling of being overlooked or misunderstood. At times, I felt like I was advocating not only for others but also for the legitimacy of their pain and stories. Leadership can be lonely, especially when you are building something that doesn’t yet exist or trying to hold communities together during a crisis.

Youth mentorship has brought its own heartbreak—walking with young people through violence, incarceration, addiction, or loss, and knowing you cannot fix everything. Accepting that presence is sometimes more powerful than solutions was a hard lesson.

Yet every struggle refined my sense of purpose. The road hasn’t been smooth, but it has been meaningful. The obstacles taught me humility, resilience, and compassion—and reminded me that healing doesn’t come from avoiding brokenness, but from staying present within it.

Alright, so let’s switch gears a bit and talk business. What should we know about your work?

My work lives at the intersection of spiritual care, trauma response, and community leadership, especially among immigrant, refugee, and at-risk communities. For more than 25 years, I have served as a pastor, chaplain, educator, and nonprofit leader—often showing up in the moments people never plan for: loss, crisis, grief, and rebuilding.

I began my journey working with youth and families in the Middle East, where I directed summer camps and taught philosophy. Those early experiences shaped my lifelong commitment to mentorship and formation, particularly for young people searching for direction in difficult circumstances. After immigrating to the United States, my work expanded across parishes, schools, and community institutions on both the East and West Coasts.

Today, I am best known for my chaplaincy and trauma-informed work in Los Angeles. I serve as a police chaplain and as lead chaplain for the Los Angeles County Probation Department, accompanying families, first responders, and justice-involved individuals through moments of violence, uncertainty, and profound loss. Alongside this, I continue to lead parish and mission communities throughout California and remain deeply involved in humanitarian and nonprofit initiatives centered on youth leadership, healing, and human dignity.

What I am most proud of is the quiet, often unseen impact of the work—being present when people feel most alone, helping young people discover purpose, and building trust between faith communities and public institutions.

What sets me apart is my lived experience. Having survived war, displacement, and the long road of rebuilding, I don’t approach this work as theory. I meet people where they are, with empathy shaped by experience and a belief that healing begins when someone feels truly seen and not alone.

How do you think about luck?

I don’t often think of my life in terms of luck. Many of the defining moments in my journey—war, displacement, immigration, loss—would never be described as “good luck.” At the same time, I recognize that I have been deeply fortunate in ways that are not accidental.

What some might call bad luck forced me early on to adapt, rebuild, and learn how to stand again after loss. Those experiences shaped my ability to walk with others through trauma, uncertainty, and grief. They didn’t make the road easier, but they made my work more honest and grounded.

What some might call good luck has often shown up as people—mentors, colleagues, and communities who trusted me, opened doors, and walked alongside me when the path forward was unclear. I’ve also been fortunate to be in the right place at the right time to serve—whether during crises, moments of public tragedy, or private loss—where presence mattered more than planning.

Ultimately, I see “luck” less as chance and more as responsibility. Every opportunity I’ve been given—especially the trust of people in their most vulnerable moments—has carried an obligation to show up with integrity, compassion, and humility. If there is any luck in my life, it is the privilege of being allowed into people’s lives when it matters most, and the strength to keep answering that call.

Contact Info: