Today we’d like to introduce you to Deborah Aschheim

Hi Deborah, we’re thrilled to have a chance to learn your story today. So, before we get into specifics, maybe you can briefly walk us through how you got to where you are today?

I was trained as a sculptor, and for much of my career, I made room-sized installations, often incorporating light, sometimes video and sound, that tried to conjure up invisible worlds of biology and neuroscience. I made landscapes of blown-up invented viruses (this was decades before Covid), http://deborahaschheim.com/projects/more, and “nervous systems for buildings” http://deborahaschheim.com/projects/index/neural-architecture, and I mapped my own neural networks of memory across the space of galleries and museum, building web-like installations around fragments (video clips) of our family home movies (http://deborahaschheim.com/projects/index/on-memory.)

In 2009, I was invited to be the inaugural Hellman Visiting Artist at the Memory and Aging Center in the Department of Neurology at UC San Francisco (UCSF), (http://deborahaschheim.com/collections/view/374). I loved working alongside doctors and scientists trying to understand the diseases of memory and forgetting, and I was deeply moved by patients who, despite facing a terminal diagnosis, made space to invite me and my musician collaborator Lisa Mezzacappa into their lives with the hope that their participation to science and art might help other people. This experience of being embedded in a non-art institution transformed my relationship between art and life. Although I still made installations for galleries and museums, increasingly I wanted to make things for other kinds of spaces, like the hospital waiting room where you wait to see the neurologist, or the bus stop where you wait for the bus, or to park where you come to unwind from the stress of the city. I was thrilled to have the opportunity to be “embedded” in other people’s worlds, with the idea that my status as an artist could be a kind of passport into experiences and lives that were different from my own.

Since UCSF, I have been artist in residence for Santa Monica Fire Department and at Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center, an amazing LA County brain and spinal cord research and rehab facility in Downey, CA. I spent weeks in Western PA getting to know rehab and vision patients living lives that are not limited by their disability, for University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Mercy Pavilion. (https://www.upmc.com/locations/hospitals/mercy/about/mercy-pavilion/art-installations/pavilion-art/patient-portraits.)

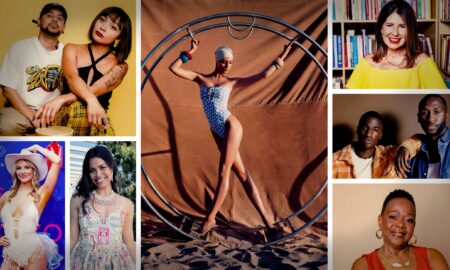

In 2019-2020, I was the Creative Strategist/Artist in Residence (CS/AIR) for Los Angeles County Registrar-Recorder (RRCC), the department that oversees elections for the largest (10 million people!) and most diverse electoral district in the US—my job was using art in outreach to historically underrepresented communities of voters. (http://deborahaschheim.com/projects/index/public, https://www.instagram.com/365daysofvoters/). CS/AIR is a program of LA County Department of Arts and Culture. The CS/AIR program embeds artists in County Departments to develop, strategize, promote, and implement artist-driven solutions to civic issues. During my yearlong residency, I worked with voters in Antelope Valley up in North LA County all the way south to Long Beach, from Santa Monica East to Claremont, including diverse language speakers, new citizens, justice impacted people, people experiencing homelessness, low wealth communities, people with disabilities, first time voters, LGBTQ+, to help make voting accessible. You can see some of the projects I did with students on 10 Cal State and community college campuses: http://deborahaschheim.com/collections/view/392.

I drew a lot of the voters and future voters I met, and we posted the drawings, along with people’s stories about why they are excited to vote, on social media. The project encouraged peer-to-peer messaging: hopefully people would repost their portraits and inspire their friends to vote. I drew people I met at the LA Zoo, on high school and college campuses, at Pride events, at resource fairs, at Homeless Connect. I drew brand-new US citizens at Immigration and Naturalization Ceremonies, and I drew voters and poll workers at vote centers. When we were sent home in March 2020 because of Covid19 and we could not longer gather, I started letting people send me selfies. The project expanded across the U.S. In the end I drew over 750 people, you can see them all here: https://www.instagram.com/365daysofvoters/, http://365daysofvoters.com/

Over 500 of the voter portraits are currently installed (through 2025) at Terminal 3 of Los Angeles International Airport (Delta Baggage Claim) alongside 5 large, new drawing based on historic images depicting the fight to expand and protect the right to vote. Please check it out! It’s pre-security, so you don’t need a boarding pass to see the installation.

Since my time at RRCC, I have remained committed to helping people vote. I work with a volunteer group called Artists 4 Democracy, we do voter outreach for each election (https://www.artists4democracy.com/, https://www.instagram.com/a4d_artistsfordemocracy/).

My practice these days is focused on public art projects that I create locally and around the country, based on deep level community engagement. Someday, I would like to make some immersive installations again, that you experience by going to special room with no windows to have a compelling aesthetic experience. It’s fun to do projects where you can control almost every aspect of the space, but for me in this critical moment, it doesn’t feel as relevant to be connecting with the small art gallery audience when there is so much work art can do to engage people outside of the gallery. Since 2016, many things I care about in America and the world have come under attack, the work of sharing stories and trying to help people connect with each other and with our institutions feels too urgent.

We all face challenges, but looking back would you describe it as a relatively smooth road?

I’m not sure I know any artists or small businesses that would say they enjoyed a smooth road. One of the ironies of being a professional artist is that I, like a lot of people, was drawn to art as a child and a teenager because it was a relief from the hyper-competitive academic and athletic world of school. The art room at school was a “safe space” where there was more than one right answer. But then, as you go on in this field, since there is a real scarcity of viable professional opportunities, the competition for galleries, grants, teaching jobs, commissions, is more extreme than many of your peers experience in their non-art career paths.

The inequities of the “art world,” which is essentially an unregulated luxury goods market, and of academia, with its arcane tenure track process and increasing overreliance on at-will “adjunct” faculty, are well documented. Like a lot of people, I struggled to find a teaching position that I could tolerate (I loved the students but I hated being part of a faculty) and a gallery I could exhibit at (without compromising what I wanted to make to create what the galleries wanted to sell.) Now I have a primarily public practice. Public art is stressful and hyper-competitive, but it gives me a way to be an artist in the world and in community, and there is something I like about the transparency of publicly funded projects. There is a lot of negotiation, and administration, and risk, and you don’t get to do whatever you want, but I have never gotten to “do whatever I want.” I like that I am part of government in some way. When people criticize government I can point to things we are doing in the arts and culture sector and say, that is government. Your taxes paid for this really cool thing.

I am part of the movement to try to make public art practice more accessible. Right now, one of the criteria for getting a public art commission is prior public art experience, that is kind of a head scratcher. And there are financial and other obstacles to making opportunities equitable, particularly for artists who don’t have personal wealth, professional connections and a graduate degree in art. This creates a privileged class, and underrepresentation for the rest of the talented hardworking artists.

I have been working to help create mentorship opportunities for emerging artists and to help build support structures that challenge the idea of art as a “zero-sum” game where someone else’s success is viewed as threatening to your own chances. I also want to be in rooms where we give voice to artists’ critique of economic and other aspects of creative practice that are not sustainable.

I hope one day we will see the cliche of “artist’s struggle” as what it is—not a romantic narrative of creative growth but an indefensible lack of economic support and equitable access to arts and culture, an area we need to reform to have a healthy society where creative people can survive and contribute. We can’t have thriving communities without arts and culture. I think all the mythologies that romanticize poverty, including artists’ financial struggles, are really destructive.

Alright, so let’s switch gears a bit and talk business. What should we know about your work?

My work is about memory and place. I make installations, sculptures, drawings, digital and social media projects and temporary interventions into public space. I work mainly in the public realm. My projects are often based on historical research and deep level community engagement.

I use drawing as a way of connecting directly with communities, and much of my recent work shares stories and portraits of project participants I meet through community engagement. Other projects are based on historical research, often into histories of civil rights and voting rights movements, which I connect with documenting contemporary activism from my perspective as both a participant and observer. My vernacular history projects explore themes of collective memory, oral history and social justice to bring the stories of diverse communities to life.

I suppose one thing that sets me apart is how deeply I dive into research in archives and the way I collaborate with project participants. Often I will draw and interview everyone who is willing to talk to me to try to understand the real stories people share with each other, which are often different stories than “official” versions of history. I want my projects to be a platform for people to share their own stories, and to have control of how they are represented, so I work very closely with project participants. I revising their portraits and we edit their stories together until they tell the story they want to share.

I studied Anthropology in college, and I think sometimes the work I am doing at this stage of my career is based on the idea I had of what Anthropologists’ work might be, when I first heard of the discipline at age 18. I thought as an Anthropologist, I might meet people whose lives were different from mine, and embed themselves in their worlds, to try to understand and communicate what their lives are like, so that we might all appreciate each other better. And I wanted to get perspective on myself, to try to understand how it might feel to be someone other than me. That wasn’t exactly what it turned out Anthropologists really do, or at least that was not the focus of the field back when I was in college. I think (hope) there was a period of institutional reform that came later. But that vision I had at age 18 informs the community based work I do today.

What matters most to you? Why?

What matters the most to me right now is that you vote this fall, and that you make sure everyone you know is voting. If we lose our democratic society where all people are equal, nothing else matters.

That is why I made the “Milestones” drawings you can see at LAX. I want people to know that throughout the 20th Century, not that long ago, people fought and even died to expand the right to vote. The drawings depict milestones in voting rights in America and are inspired by historic photographs, used with permission, from the following archives:

“Suffragettes Mrs. J. Hardy Stubbs, Miss Rosalie Jones with flag, c 1910-1915, after George Grantham Bain News Service,” source image courtesy George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress, LC-B2- 2472-12.

The demand for women’s right to vote gathered strength in the United States in the 1840s, but individual states did not begin granting women the right until 1869. The 19th Amendment, guaranteeing that the right to vote “shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex,” became part of the US Constitution in 1920.

“Women Activists with signs for voter registration, September 8, 1956, after Cox Studios,” source image courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Frances Albrier Collection.

After the Civil War, Congress ratified the 15th Amendment (1870) which guaranteed that the right “to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” granting African American men the right to vote. This image documents the San Francisco Chapter of the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) efforts to register voters and educate Bay Area residents on their right to vote as a part of the Citizenship Education Project, which was jointly sponsored by the NCNW and the National Urban League.

“Three African American women at a polling place, November 5, 1957, in New York City or Newark, New Jersey after Thomas J. O’Halloran” source image courtesy of U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, C-U9-1097-E -10.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, a landmark piece of federal legislation that prohibits discrimination in voting, created a means of enforcement to protect the voting rights of racial minorities, particularly in Southern states with a history of discriminatory voting practices. The Act required jurisdictions to obtain prior federal approval before making any changes to voting rules. Congress reauthorized and expanded these provisions five times between 1965 and 2006. The 2013 Supreme Court decision Shelby County vs. Holder overturned various provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, clearing the way for states to impose policies that make it harder for historically vulnerable populations to exercise their right to vote.

“Demonstration for reduction in voting age, 1969, after photo by Tom Barlet”, source image courtesy of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer Digital Collection, Museum of History & Industry, Seattle, WA.

The movement to lower the age of voting eligibility from 21 to 18 was driven by the military draft of 1942, which required men between the ages of 18 to 21 to register and to serve in combat operations, if needed. Supporters argued that if citizens aged 18 to 21 were required to fight and risk death in combat then they should have a say in electing the lawmakers who /authorize these wars. The movement gained momentum in the 1960s, when younger generations were also mobilizing against the war in Vietnam.

“Eighteen-year-olds now eligible to vote registering at Westchester High School, Los Angeles, 1971, after Frank Q. Brown,” source image courtesy of Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive, UCLA Library Special Collections.

The 26th Amendment, ratified by 75% of US states in 1971, established a nationally standardized minimum age of 18 to vote in state and local elections, lowering the age of eligibility from 21. Despite the passage of this amendment, youth voters (people aged 18 – 29) still have the lowest registration and turnout rates out of any age group in the country. Many states have passed laws allowing online registration as well as pre-registration, as part of the drivers’ license application process, to encourage a higher turnout of young voters.

Contact Info:

- Website: deborahaschheim.com, 365daysofvoters.com, pasadenatimetravel.com, neverfacebook.com

- Instagram: @365daysofvoters, @robinsonparkproject, @raleighstories, @sunvalleystories, and @justice.drawings

Image Credits

Deborah Aschheim (artist photo): Photo by Monica Almeida, photo courtesy of Los Angeles County Department of Arts and Culture.

01_Aschheim_Detail_365DOVandMilestones, Photos by SKA Studio LLC., courtesy of Los Angeles World Airports.

02_Aschheim_Milestones, Photos by SKA Studio LLC., courtesy of Los Angeles World Airports.

03_Aschheim_LAWA_Intallation, Photos by SKA Studio LLC., courtesy of Los Angeles World Airports.

04_Aschheim_1956_NMAAHC: credit: Deborah Aschheim

05_Aschheim_365DOVdetail: credit: Deborah Aschheim

06_Aschheim_ChicanoMoratorium2022: credit: Deborah Aschheim

07_Aschheim_UPMC_Mercy_Pavilion_portraits: credit: Deborah Aschheim

08_Aschheim_MotherandChild: credit : Zoë Taleporos