Rooted in slowness, care, and community, Little Moss is Xiao He’s gentle resistance to a world that rushes childhood creativity toward outcomes and optimization. Drawing from her experiences as an artist, former tech worker, and immigrant navigating uneven access to arts education, Xiao has built a children’s art program that values process over polish and presence over performance. Through workshops held in libraries, playgrounds, and shared public spaces, Little Moss creates room for children — and their caregivers — to explore imagination without pressure, rediscover creativity as a shared language, and grow in ways that are subtle, human, and deeply lasting.

Hi Xiao, thank you so much for taking the time to share your story and insights with our readers. Little Moss is such a thoughtful and community-rooted project, so let’s dive right in. You describe Little Moss as inspired by “quiet growth.” How did that philosophy take shape for you, and why did it feel important to create a children’s art program that resists rushing, optimization, or commercialization?

The idea of “quiet growth” came from both my art practice and my lived experience. In nature, moss grows slowly and persistently. It doesn’t announce itself, compete for attention, or try to scale. Yet over time, it transforms entire surfaces. That metaphor stayed with me.

In children’s creativity, I noticed how often growth is rushed or instrumentalized: classes are outcome-driven, optimized for display, or treated as enrichment for future achievement. I wanted to create a space that pushed back against that logic.

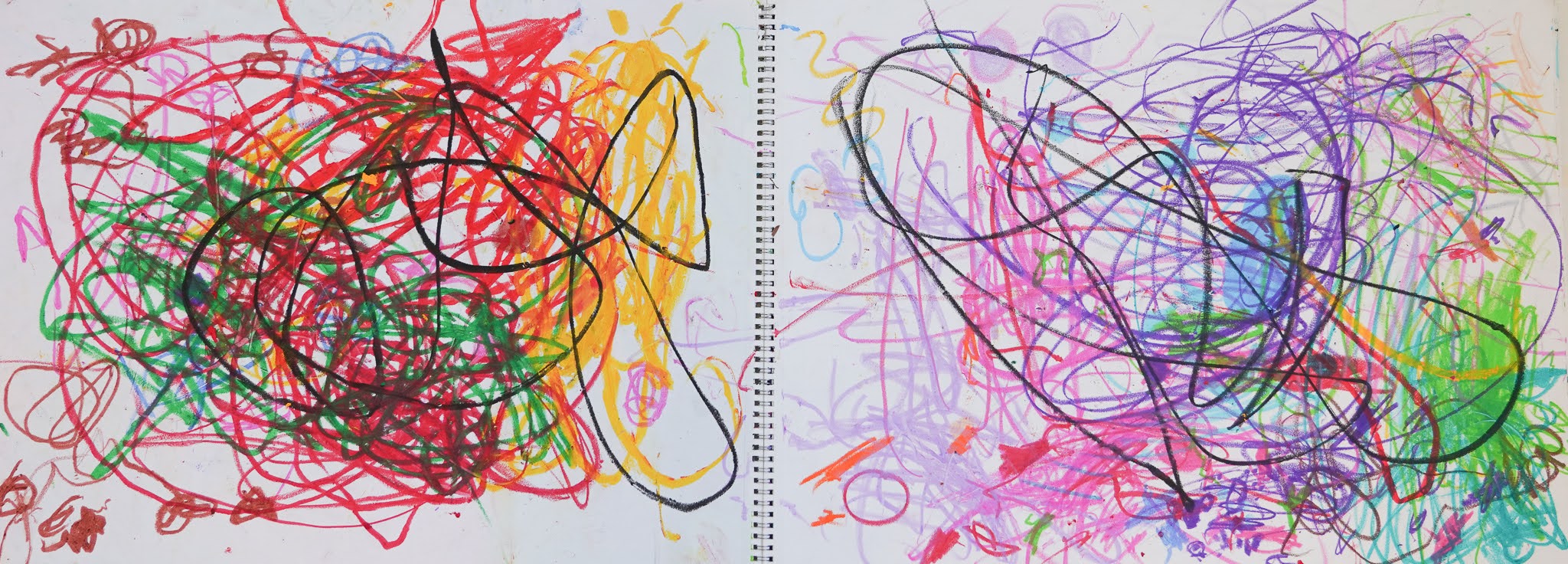

Little Moss is built around the belief that creativity doesn’t need to be productive to be valuable. Children need time to linger, repeat, abandon ideas, and return to them. When we remove pressure and speed, something deeper emerges: confidence, curiosity, and a sense of ownership over their imagination. That’s the kind of growth I wanted to protect.

You’ve spoken about your background as a practicing artist, former tech worker, and immigrant navigating multiple education systems. How did those experiences shape your understanding of access to creative education, and how do they influence the way Little Moss is designed today?

As an immigrant, I moved through multiple education systems where access to creative education was uneven and often tied to privilege: private lessons, studio access, or parents who had time and cultural familiarity to navigate those spaces.

Later, working in big tech, I saw the opposite extreme: systems optimized for efficiency, metrics, and scale. While powerful, that mindset often strips away slowness, ambiguity, and care, the very conditions creativity depends on.

Little Moss sits at the intersection of those experiences. It’s designed to be accessible, welcoming, and embedded in everyday community spaces like libraries and playgrounds. We bring the materials, structure, and care so families don’t need prior knowledge or resources. And we intentionally resist over-optimization, choosing depth and presence over speed or volume.

Little Moss workshops emphasize process, storytelling, and open-ended exploration rather than polished outcomes. What have you observed in children—and in parents—when creativity is approached this way instead of through more rigid or outcome-driven models?

When outcomes aren’t the focus, children relax almost immediately. They take more risks, change direction freely, and narrate their work with surprising emotional clarity. Instead of asking, “Is this good?” they start saying, “This is my story.”

What’s been equally powerful is what happens with parents. When adults create alongside their children, rather than supervising or correcting, something shifts. Parents slow down. Conversations emerge naturally. The workshop becomes a shared experience rather than a performance or lesson.

This process-centered approach turns art into a language, a way for children to express memory, emotion, and imagination, rather than a task to complete.

Over the past year, you’ve reached hundreds of children and caregivers through workshops in libraries, playgrounds, and community spaces. What moments or reactions have stayed with you most and reaffirmed that this work matters?

Many small moments stay with me: a child carefully explaining the “backstory” of a clay sculpture; a parent telling me it was the first time they’d sat down to make art with their child; families returning to multiple workshops and greeting one another like a community.

One moment that stands out was a parent saying, “My child usually gets frustrated in classes, but here they didn’t feel wrong.” That sentence captures why Little Moss exists.

It’s not about producing artists. It’s about creating spaces where children feel seen, capable, and free to explore who they are.

As Little Moss enters a new growth phase—expanding partnerships, developing storytelling-based workshops, and formalizing a nonprofit structure—what excites you most about what’s ahead, and how are you thinking about scaling while protecting the soul of the project?

What excites me most is deepening the work, not just expanding it. We’re developing storytelling-based workshops that integrate making, narrative, and memory, and building partnerships with libraries, community centers, and fellow artists.

When I think about scaling, I think less about size and more about integrity. Growth should feel like replication of values, not dilution. That means training collaborators carefully, designing workshops that remain open-ended, and staying rooted in public, accessible spaces.

For others who are feeling called to leave fast-paced, optimized systems to build something slower, more human, and community-centered, what lessons have you learned so far that you wish you’d known at the beginning?

One lesson is that slowness is not a lack of ambition. Building something human-centered requires patience, trust, and a willingness to grow without constant external validation.

Another is that community work compounds quietly. You may not see immediate metrics, but relationships deepen, and impact accumulates in ways that numbers can’t always capture.

Finally, I’ve learned that protecting the soul of a project requires saying no: to speed, to misalignment, to growth that feels extractive. That clarity is what allows the work to last.

Links:

Popular

-

Democratizing Hollywood Sound: How Alec Puro Built Viralnoise for the Creator Economy

-

Hope Jewelry Co. Opens Its Doors: Handmade Jewelry, Matcha, and Community Connection

-

Embodiment Over Ego: Kathleen Aharonian on Healing, Self‑Love, and Living From the Body

-

Cultivating Creativity Through Quiet Growth: Inside Xiao He’s Little Moss

-

Running Toward the Desert: Faith, Identity, and the Courage to Begin Again

-

Portraits of the Valley