Today we’d like to introduce you to Sierra Domb.

Hi Sierra, thanks for sharing your story with us. To start, maybe you can tell our readers some of your backstory.

My name is Sierra Domb. My journey to becoming the founder of a global nonprofit organization, a health communicator, and a research collaborator began long before I fully understood the challenges I would face.

In many ways, my journey began at the University of Miami. Having struggled with Autoimmune Dysregulation (AD) and Erythromelalgia (EM) since childhood, both conditions were largely under control by the time I reached young adulthood through a combination of corticosteroids for AD and lifestyle changes for EM. As a teenager, I tried my best to balance school, extracurricular activities, and social life while managing frequent doctor’s visits, chronic pain, and periods of being immunocompromised that often kept me from attending school as much as I wanted.

In my youth, I let societal pressures shape my desire to fit a narrow, simplistic version of “normal.” I struggled to appear okay on the outside while enduring physical and emotional pain on the inside. Despite my efforts, I often failed to hide the changes in my appearance caused by the side effects of my conditions and the medications needed to manage them. People frequently reacted with shock and confusion, expressing their negativity through daily bullying and harassment. This caused me to put up walls around others, always feeling like I had to be on the defensive. I longed to be like everyone else and wrestled with accepting my health challenges. Back then, I resented feeling different and feared I would never be “good enough” to keep pace with my peers. After a few painful attempts to open up about my medical struggles, I withdrew completely and stopped sharing.

I had never experienced true health in my adolescence, but arriving at university marked a turning point. For the first time, life felt full of possibility, and my goals seemed attainable. Ready to move beyond the hardships of my medical journey, I embraced new opportunities, such as working as a writer and photographer, studying communication, and hosting a music radio show on campus. For the first time, I was surrounded by nothing that reminded me of my health struggles.

My time on the radio in Miami opened the door to commercial and animation voiceover work. I left university and moved to Los Angeles after securing opportunities in the industry and began a new chapter as a voice actor.

While there, I received a call that someone close to me had become seriously ill. I moved from Los Angeles back to Miami to care for my loved one and remained their caregiver until they passed away. Even while still ill, they encouraged me to return to school and complete my degree. After their passing, I felt a strong, sentimental calling to re-enroll at the University of Miami, and so I did.

I began taking classes again in Miami, picking up where I had left off before pursuing voiceover work. But I no longer felt the same passion for general communications, my radio show, the arts, and the things I had once loved. The loss of my loved one shifted my perspective, making those passions feel less important, and I struggled to find purpose in activities that once brought me joy.

Shortly after, in 2015, I developed Visual Snow Syndrome (VSS) at the age of 21. My VSS came on gradually over the course of a day, with subtle symptoms appearing in the morning and full onset hitting later that day while I was driving back to school from a nearby food shop. Suddenly, my vision went black behind the wheel for a moment. When it returned, I was left with relentless visual disturbances, including flashing lights, double images, and distortions, alongside tinnitus (ringing in the ears), paresthesia (tingling sensations throughout the body), and derealization. My memory felt fuzzy, migraines were constant, and above all, I was gripped by fear about what was happening to me.

With mortality fresh on my mind, I wondered if I might also face a fatal outcome. Doctors only reinforced this fear as they knew nothing about VSS and misdiagnosed me, suggesting possible blindness or death due to neurological symptoms often linked to degenerative and terminal illnesses. I desperately tried to explain a condition I barely understood myself. Some doctors even questioned my sanity, having never seen symptoms like mine before. Despite undergoing every test imaginable, nothing showed up abnormally.

I was experiencing something very real, and my symptoms were constant, there 24/7, but modern medicine still had not caught up. At the time, I didn’t know I was one of millions of people of all ages with VSS who had been disbelieved, marginalized, misdiagnosed, and mistreated by the international medical community.

I left school once again, gripped by uncertainty about whether I might lose my sight or even my life at any moment.

Overwhelmed by my health worsening to its most severe level, and feeling utterly alone with no one who understood what I was going through, I was filled with fear for what the future might hold.

Like many who face setbacks when the medical community fails them, I turned to the internet searching for answers, a resource that can be both enlightening and cathartic but also misleading and overwhelming depending on the information available.

Seeking emotional support online, I found others living with VSS, but the experience was deeply mixed. I reached out with questions, hoping for advice and understanding. Some responded with kindness, sharing their own stories and offering comfort. Yet others reacted harshly, repeatedly urging me to end my life, insisting that this condition was a death sentence and that my circumstances would never change. When I asked questions, some became angry, and after learning I was a woman, some responses took a disturbing turn.

Despite this, I stayed connected with those who showed empathy and eventually reunited with many of them through my future advocacy work. It was clear that countless individuals were suffering, feeling isolated and powerless after being failed by the medical community. Compounded by the debilitating visual and non-visual symptoms experienced by people with VSS of all ages, the medical community’s history of negligence, mishandling, and lack of knowledge was having devastating consequences. This further impacted patients’ physical and mental health, challenges everyone often faces at some point in life, but made worse by these circumstances. My heart ached for them.

One of the important discoveries I made was an academic paper about a condition called Visual Snow Syndrome (VSS), which described my symptoms exactly. I reached out to the paper’s author, neuroscientist and Brain Prize winner Dr. Peter Goadsby, who diagnosed me with the condition. Dr. Goadsby explained that despite the validity of VSS and its widespread global impact, most patients are still dismissed by medical professionals.

The profound lack of understanding and resources for VSS worldwide was staggering, leaving me to navigate a confusing maze of uncertainty and skepticism until I connected with Dr. Goadsby. He told me there were only a handful of researchers studying VSS, but their efforts to advance awareness, scientific legitimacy, and treatment options were stalled due to no funding.

This struggle sparked a deep determination within me. With funding nonexistent, research at a standstill, and millions of individuals of all ages worldwide affected by VSS, I felt compelled to take action.

In 2018, I moved back to Los Angeles at the age of 23. That same year, I organized the first-ever Visual Snow Conference, which was held at UCSF, to bring together global researchers and individuals living with VSS. I also founded the Visual Snow Initiative, a nonprofit organization created to raise awareness, expand education, foster scientific recognition, and advance medical research for VSS.

From the very start, I never felt qualified to run a nonprofit. I was operating on autopilot, shocked and numb, as I dealt with my debilitating VSS symptoms. Yet, I was driven by the need to change my circumstances and simply tried my best while navigating immense challenges.

Founding the Visual Snow Initiative was my way of coping with the traumatic journey of developing VSS, just as I felt my life was finally starting to heal from earlier medical struggles and a fulfilling future seemed within reach.

We all have the capacity to evolve, and it’s natural for our personal and professional interests to change over time. For me, that shift came after developing Visual Snow Syndrome. Before then, I had learned to adapt and persevere through medical challenges that deeply affected my adolescence and, to a lesser extent, my young adulthood. I managed those challenges quietly, pushing myself to fit the mold of “normalcy”: striving for an average young adult life and hoping to control or even forget my health issues.

But VSS changed everything. The shifts in my vision and sensory processing were the tipping point. Unlike my previous conditions, VSS came with no awareness, support, or solutions due to its lack of recognition by the global medical community and absence of treatment options. I understood the emotional toll of chronic illness, and while I always fought to overcome my struggles, this time I couldn’t just push through.

Instead of simply adding another medical condition to my story, I chose to shift gears: I became an advocate, channeling my experience into raising awareness and working to make a difference in the world. Refusing to let VSS stifle my ambition, I changed my outlook completely.

Despite new challenges from my VSS and working to advance VSI full time, I eventually graduated from the University of Miami, where I shifted my academic and professional focus to health communication. I was eager to bridge the gaps I noticed in how medical information was shared. I quickly realized there was a significant disconnect between what doctors and researchers understood and how that vital knowledge was communicated to and received by patients. My driving passion became making complex medical concepts accessible and ensuring patient voices were heard and valued.

To deepen my understanding of human behavior and research methods, I concentrated on behavioral sciences and qualitative data analysis. I am a strong advocate for multiculturalism, which has been central to my identity and my family’s. Fully aware of the importance of maintaining a broadminded perspective, especially since many people tend to view the world only through the lens of those similar to themselves, I sought to focus on the global picture rather than just my immediate surroundings. This led me to study intercultural communication as well.

VSI became a global mission born out of necessity and a catalyst for progress, allowing me to apply everything I had learned about health communication in a meaningful way. Through this work, we have been able to inform the public about VSS, fund medical research for VSS in seven countries, share essential educational resources, and build strong collaborations with doctors and researchers worldwide to advance clinical recognition and generate new research discoveries for the condition. Rooted in science, collaboration, health literacy equity, compassionate communication, and my own personal and professional experience with VSS, I am grateful that this work can play a part in improving the landscape for those living with VSS and for those working to better understand and treat it.

My work also led to another way to help drive change on a global level: an invitation to join the International Advisory Board for the Columbia WHO Center for Global Mental Health. In this role, I contribute to a wider range of global health challenges, advocate for marginalized conditions, and continue my commitment to improving health communication and access to care worldwide. I am especially focused on raising awareness about often overlooked conditions with physical symptoms that can also profoundly affect mental health and quality of life. My own experience with VSS has deepened my resolve to ensure that no one feels alone or unheard in their health journey, and it motivates me to keep humanity at the center of medicine and science.

I have also recently joined the Erythromelalgia Association and served as a guest speaker on neurological health, homeostasis, and my personal experience with EM. In addition, I collaborated with Oxford Mindfulness to expand access to evidence-based mindfulness education. As part of this work, VSI partnered with Oxford Mindfulness on the development of their app. I contributed to a module that provides free, globally accessible introductory mindfulness for those with VSS. This project was inspired by neuroscientific fMRI research showing that brain activity, especially in the salience networks, changes in people with VSS before and after Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT).

I have come to accept that while I have some control over my actions, there is so much I cannot control, including parts of my health, how others treat me for being true to myself, and the shifts happening around us all. I often wondered why life led me down this path, but I have come to accept that some things simply happen and that all I can do is see where life takes me next, whether that means stepping into a new chapter, applying my skills in new fields, staying hands-on, or moving more into the background. All I can do is try my best, knowing that so much is beyond my control and that life often unfolds while we are busy making other plans.

It might be unpopular to say, but it is true both biologically and psychologically: humans were never meant to feel happy every moment of every day. It is unrealistic, yet society and corporations push the illusion that life should be perfectly happy and permanent, when real life is far more complicated. There is so much suffering in the world, and many have endured far worse than I have. I always remind others to be mindful of this and not to pity me.

I felt deeply honored and grateful that anyone believed in what we were building and wanted to support me. Every returned message, every connection made, and hearing from people affected by VSS in 93 countries after thinking I was completely alone with this condition was humbling. Their support fueled my determination and gave me the strength to keep going.

I don’t believe everything happens for a reason, at least not in the sense that every hardship is part of a grand design. Sometimes bad things just happen, and there’s no hidden lesson waiting to be uncovered. But I do believe we can choose to make meaning from what we go through. If we look closely enough, sometimes the worst moments push us somewhere better, not always right away, but maybe years later. Sometimes they open doors we wouldn’t have found otherwise, shape us into someone stronger, or bring people into our lives we wouldn’t trade for anything.

Personally, it helps me to search for what good, however small, might come out of the bad, whether it’s becoming wiser, kinder, more resilient, or simply more awake to what matters. But I also know that not every wound leaves you with something to be grateful for. Some pain is just pain. Sometimes it’s simply about surviving, doing what you can to change what’s in your control, and finding glimmers of light where they appear.

One thing that’s never changed for me is a deep dislike for injustice and prejudice, especially when people are judged or harmed for things outside their control. That feeling has always driven me to try to make things better, even in small ways. It bothers me when cruelty or ignorance spreads harm, when rumors or shallow judgments overshadow the truth of who someone really is.

Helping others, whether by listening, sharing what I’ve learned, or just being there, is one of the few things that always feels worthwhile. I try to meet ignorance with empathy and education when I can, and to keep learning myself. But I also know people have to think for themselves in the end. All I can do is show up, do what I can to help lighten someone’s load, and hope that somehow my piece of effort makes things a little less heavy for someone else.

These days, in an ever-changing world, I value stability and moments of genuine peace more than ever. Living with a body that doesn’t always cooperate has made me cherish calm when it comes. At the same time, I remain passionate about creating and exploring new ideas, striving to maintain balance in how I live and work.

There’s a common idea that you have to pick just one way to be, or that there’s one “right” way to live. But most people aren’t built for such narrow categories; we’re rarely that simple. These limited definitions can feel restricting and confining. In reality, we hold contradictions and are multilayered beings.

No single event or trait fully defines me. I’m shaped by a variety of experiences, interests, and values that together create a more complete picture of who I am. For me, it’s never been about confining myself to a single path or a rigid sense of self. It’s about making room for all parts of who I am to coexist and appreciating that same complexity in others.

Someone can work in medicine or science and still have a deep love for the arts. They can be driven to solve some of the world’s biggest challenges while also needing lighthearted moments of reprieve. Compassion and kindness can live alongside strength and intellect. You can have health issues and also love playing video games, painting, or being a caring friend or partner. Sometimes, your condition is just one part of a much bigger story. Many of us aren’t defined by any one event or trait; instead, all of it weaves together into an evolving, multifaceted identity.

Different cultures, influences, and interests don’t cancel each other out; they bring complexity, perspective, and variety to life. After all, we all bleed red. As long as no one is causing emotional or physical harm to themselves or others, differences can coexist, be appreciated, and even expand our horizons. Through respectful dialogues and collaborations, these differences have the potential to help us build a better world together.

At every funeral I’ve attended, I’ve never heard anyone mention how conventionally attractive the person was, the size of their business, or how perfect their academic records were. What truly endures, and what people remember most, is how that person treated others and the feelings they inspired. It’s the kindness, compassion, and genuine connections they shared that live on in memory, far more than any superficial trait or external measure of success. I’m deeply grateful for every act of kindness and encouragement from my loved ones, VSI’s supporters, and everyone I’ve connected with through my work.

I have been through more than I ever expected. Some days I feel like a teenager cosplaying as an adult, trying her best to figure things out, and other days I feel eighty, wiser, yet worn out by all I have seen, learned, and survived. I do not take moments of happiness and peace for granted; I treasure them with gratitude for as long as they last.

Would you say it’s been a smooth road, and if not what are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced along the way?

No matter how much you plan or prepare, some things will always be beyond your control. Your health may falter, others will form opinions you can’t change, and success does not always follow a neat, predictable path. Life is unpredictable; circumstances can shift in an instant and tomorrow may look nothing like today.

The real challenge is not that you don’t fit the mold; it is that society expects everyone to fit into a single, narrow mold. This expectation is the problem. So long as no harm is caused to yourself or others, our differences should not only be accepted but celebrated. Yet many people want others to conform to their own views, often overlooking the beauty of diverse perspectives and experiences.

There are many things I can’t control: my health, others’ actions or opinions, and systemic injustices. What I can control is my own response and the actions I take. I strive to create positive change where I can, understanding that outcomes are not guaranteed and that not everyone will come to recognize or embrace that change. Still, I do my best because even a small chance to make things better is worth the effort.

Before I became involved in nonprofit work, medical advocacy, and research, my interests leaned toward creative fields like voice acting, writing, and photography, roles that allowed me to work more behind the scenes. A major hurdle I faced was overcoming the impact of past bullying and harassment, which left me hesitant to share my story publicly. I had already learned, sometimes painfully, how harsh and unempathetic people could be, and I wanted to avoid more of that.

When I was diagnosed with Visual Snow Syndrome, a complex condition that even many doctors struggle to fully understand, I realized how little awareness and recognition it received. I understood that sharing my story openly was crucial to humanizing the condition. Confronting that fear was intimidating, but I knew the potential to raise awareness, support research, and improve resources for others with VSS far outweighed the risk of judgment or criticism. At that moment, honestly, that is exactly how I felt.

Studying neuroscience, psychology, and human behavior revealed to me just how much of what drives us happens beneath the surface. Our actions and beliefs are shaped by layers of societal conditioning, personal experiences, insecurities, and projections we are often unaware of. While each of us is unique, much of who we are is influenced by unseen forces beyond our immediate awareness.

People often believe their perspective is the one true reality, projecting it as a universal truth. Understanding this helps us recognize that opinion is not fact and it is important to consider the source of information. When someone says something is impossible, is it because it truly is, or are they simply viewing the problem from a limited angle? Are their judgments based on objective truth, or on their own biases and experiences?

Passing judgment on others is easy, something many do without a second thought. But it takes real courage to try, to stand up despite the risk of failure, and to be vulnerable enough to reveal your true self. Most people never see the full truth of another; they often perceive only what aligns with their own views or what is allowed to be seen.

How someone speaks about others, especially with judgment or cruelty, says more about their own mindset than about the person they criticize. Words and actions reflect the inner world of the one who expresses them.

Ultimately, what you choose to contribute to the world is your responsibility. Whether you lift someone up or tear them down, support or dismiss, the choice reflects your character. Think back to your darkest moments: if you were in their place, how would you want to be treated?

We never fully understand what others are facing. Some may lack empathy despite everything, and in those moments, staying true to your own values and compassion is what matters most.

Whenever you introduce something new, whether it is a fresh idea, a creative work, or a sincere effort to improve a system, you can expect to encounter resistance. This resistance often arises not because the change is bad, but because it challenges established norms, comforts, and power structures. Anyone who has worked to shift a system, innovate in art, or advance genuine medicine knows this well. Progress is rarely smooth or universally welcomed from the start.

Change unsettles people. It forces them to question what they have accepted as normal or true. This discomfort can manifest as skepticism, criticism, or even outright opposition. To create a meaningful impact, you must become comfortable with that pushback. It is a natural part of growth and transformation, not a sign that your efforts are wrong or pointless.

Embracing resistance as part of the process allows you to refine your ideas, strengthen your resolve, and build deeper understanding. It is through navigating these challenges that real progress happens, step by step, sometimes slowly, but with lasting effect. Ultimately, the willingness to persist despite resistance is what separates those who spark change from those who accept the status quo.

Letting yourself be seen honestly, flaws and all, is not weakness; it’s a quiet form of strength.

I don’t chase a flawless version of life; it doesn’t exist. Some days I’m strong; some days I’m not. Some doors stay shut no matter how hard I try. But showing up still counts for something.

Life is always changing: my health, my perspective, everything in between. I don’t have to welcome every change, but I do have to live with them. I keep striving to grow, improve, and build what I can. Along the way, I’ve realized I don’t need to be hard on myself at every step just because I’m not some ideal version of myself. It’s okay to treat yourself with kindness, even if you’re still becoming who you hope to be. As you move forward, take time to notice your progress and celebrate personal victories, no matter how small.

Many of us know the mask, acting fine when we are not or dimming ourselves to make others more comfortable. For a long time, I tried to show the version of myself I thought would make others happy. But even then, you cannot be everyone’s cup of tea. If someone cannot appreciate the real you, maybe you are simply not meant to fit, and that is alright. Having faced moments that reminded me how fragile life is, I have come to care deeply about genuine connections and meaningful experiences. In a superficial world that often encourages conformity, feeds insecurity, and fixates on appearances while overlooking substance, choosing to be yourself and focusing on what you contribute and how you treat others rather than on how things look is an important act of rebellion.

Now, I’d rather show what’s real, even when it’s messy. Letting go of the idea that I could control everything made that possible. I don’t hold so tightly to expectations anymore; I take life as it comes, one piece at a time.

My work has connected me with people I never could have predicted. None of it happened because I pretended to have it all figured out. I’m truly grateful to everyone around the world, both those I’ve met and those I haven’t, who have supported me on this journey. I deeply cherish my incredible family, wonderful friends, and loved ones, and I’m thankful for their care and presence through life’s ups and downs.

Sometimes what matters most isn’t the setback itself, but how you respond to it. Did you show up despite the challenges? Did you try to make things a little better for yourself or someone else? Did you keep moving forward, even when it would have been easier to stop?

Everyone faces obstacles, whether visible or hidden, that shape their journey. The path to anything that matters is rarely a straight climb. It twists and turns, most of it unseen. It winds through peaks and valleys, moments of certainty, and times that challenge everything we thought we knew. Success, which is subjective, does not necessarily mean the absence of hardship.

We cannot control when difficulties arise, but how we find meaning amid uncertainty, how we respond after being knocked down, and how we continue when the path is far from smooth can reveal our resilience. Meaning often emerges in how we navigate what is beyond our control and still find reasons to keep showing up.

So instead of fighting myself, I try to accept who I am, flaws included. I do my best with what I have, without punishing myself for not fitting someone else’s mold. I don’t have to be in love with every part of myself every day, but I would rather not spend my life fighting it either. If I am here for the long run with myself, I would rather not be my own enemy.

So I do what I can, imperfect and still learning. I know the road won’t always cooperate, but I also know there is often something to learn along the way.

Thanks for sharing that. So, maybe next you can tell us a bit more about your work?

At the time of this interview, my work is multifaceted, including global education on marginalized medical issues and health communication consulting. However, my primary focus over the past several years has been on Visual Snow Syndrome (VSS), a neurological condition that can affect vision, hearing, cognition, sensory processing, and overall quality of life.

At 21 years old, I first began experiencing symptoms of Visual Snow Syndrome, which researchers estimate affects 2-3% of the global population. In 2018, at age 23, I founded the nonprofit Visual Snow Initiative (VSI) to raise awareness, enhance education, foster scientific recognition, and support research for VSS. This work was driven by my own painful medical journey, as well as the struggles faced by millions of others worldwide across all ages. Beyond the challenging visual and non-visual symptoms, many VSS patients have also endured mistreatment, misdiagnosis, marginalization, and disbelief. These issues stem largely from the historic widespread lack of knowledge and resources about VSS within the global medical community, all of which have worsened many patients’ conditions and had devastating effects on their health.

After learning from researchers that their work stalled due to funding shortages, I established a Global Research Team for VSS. This sparked collaborations in seven countries and revitalized funding at institutions worldwide, such as UCLA. Since 2018, VSS research has quadrupled, leading to advances in biomarkers, pathophysiology, symptomatology, and treatment options. Together, we created the first official diagnostic criteria for VSS, the first Global Physicians Directory for VSS, and multimodal educational materials for healthcare providers and patients. We also founded and organized international events like the Visual Snow Conference to unite researchers and those affected.

I collaborated with the AnCan Foundation to launch the first video chat support group for VSS and partnered with the Oxford Mindfulness Foundation to develop a globally accessible app module tailored for VSS. This module integrates evidence-based therapies informed by clinical research into VSS’s unique neurological and perceptual features, including brain network differences.

One of my goals, which many said was impossible, was leading the effort to secure the first official scientific recognition of Visual Snow Syndrome, a condition with both visual and non-visual symptoms, and its hallmark symptom, visual snow, in the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases, 11th Edition (ICD-11). Despite clinical cases dating back to 1944, VSS and patients’ experiences were long dismissed. Many were wrongly labeled as imagining symptoms or “crazy,” leading to neglect, exclusion, inappropriate treatment, and tragic outcomes including suicide. Some symptoms were even attributed to supernatural causes, delaying care. The 2024-2025 ICD milestone marked the first global medical authority recognition of VSS as a legitimate condition, thanks to growing awareness, research, and advocacy.

After joining the International Advisory Board for the Columbia-WHO Center for Global Mental Health, I contribute by challenging stigma around neurological and neurodevelopmental disorders with severe symptoms and limited resources. I also advocate for improved care and access in underserved areas.

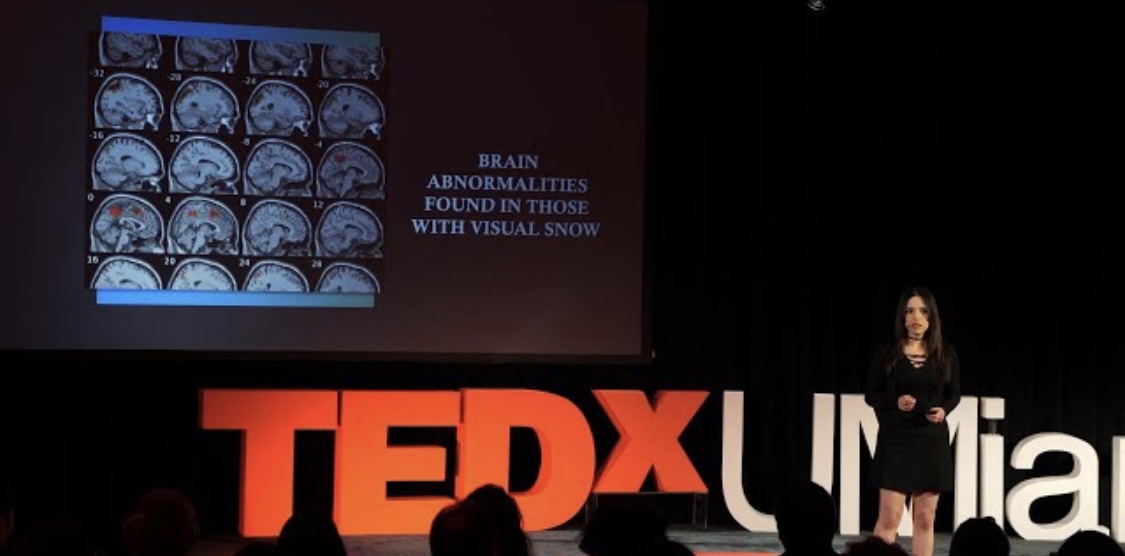

Beyond raising awareness, I explore ways to improve lives for those with complex health challenges by sharing practical, evidence-based methods. I’ve spoken as a guest for The Erythromelalgia Association on neurological health and homeostasis, and delivered a TEDx Talk sharing my VSS experience and how it inspired VSI’s founding. As someone who left school and later returned to complete my education while managing health challenges, I was grateful to be included in UMiami’s 30 Under 30 list for the global and local impacts of my work.

I believe what helps me contribute in a unique way is my willingness to take different approaches when traditional solutions fall short. I don’t accept that something is impossible just because the usual paths have been tried. I’m comfortable forging my own way and taking actions others might hesitate to take, especially if it can lead to meaningful change.

I don’t rely on groupthink or popular, mainstream opinions to form my views. Instead, I consider all factors, apply critical thinking, balance science with compassion, and stay open-minded. When I truly believe in something, I’m not afraid to take the road less traveled, or even one that hasn’t been traveled at all. The only way to know if something works is to try, so I commit fully to every effort. While trying increases the chances of success, nothing is guaranteed; I simply do my best and see what happens.

Bringing humanity back into medicine and science is essential. These fields don’t have to feel so sterile or confusing. Clear, compassionate communication benefits physicians, patients, and researchers alike.

I enjoy connecting people from different backgrounds and disciplines by identifying shared goals and complementary strengths. Combining skill sets that don’t usually overlap often creates powerful results. I embrace complexity and honor the nuanced, multifaceted nature of the challenges we can address when we work together, regardless of different titles, disciplines, or backgrounds.

In my current work, this often means bringing together patients, medical professionals, and academics to collaborate. Medicine and research rely on rigorous methods and evidence, but patients offer invaluable lived experience. Their perspectives and data should help shape the process. Beyond validation, patients need practical resources, tangible solutions, and accessible education.

Too often, people remain siloed in their own fields. When diverse voices come together, we gain a better understanding of what’s truly possible, even within constraints.

Growing up in a multicultural family with varied identities, ethnicities, and beliefs taught me that unity is rooted in compassion and respect, not uniformity. We do not all have to approach things the same way, and that diversity should be embraced because it makes life more enriching and can inspire new perspectives and innovations.

Too often, people get caught up in superficial differences, ego, or self-interest, expecting others to think, look, or act like them or to conform to what serves their agenda. This mindset hinders collaboration and progress. True significance lies in a shared commitment to moving forward together and an appreciation of our common humanity.

Any advice for finding a mentor or networking in general?

Whether you’re looking for mentorship or collaboration, ideally, meaningful connections should be built on substance rather than status. But in certain fields, especially in science, medicine, and research, titles and long CVs still carry a lot of weight. Years ago, as a young professional without the traditional credentials like a PhD or doctorate, I had to rely on my background in health communication, human subjects research, and behavioral sciences to prove my worth by showing how my perspective added value and aligned with others’ interests. I also reshaped how my background in voice acting, writing, and the arts prior to my professional pivot was viewed, highlighting it as a strength that brought fresh ideas and helped me communicate complex concepts clearly and creatively within science, medicine, and research.

When others may seem more qualified on paper or have advantages in certain environments, proving yourself often becomes part of the process, especially when you know you have something valuable to offer. In my case, partly because it was obvious, I didn’t try to hide or distract from it. Instead, I leaned into the fact that I came from a different field. Rather than seeing it as a disadvantage, I framed it as a strength: I could offer a fresh perspective and apply new strategies, especially in areas where traditional approaches weren’t making progress. In the context of problem-solving, that kind of difference can be exactly what’s needed.

Reaching out to more people can improve your chances, but it’s also important to consider how well they fit with your goals, lead with authenticity, and demonstrate the value you offer. In addition to connecting through any mutual contacts, if you’re reaching out without an existing connection, use accessible strategies to improve your chances. Be clear about not only how the mentorship or collaboration could benefit you, but also what you bring to the table and how it can benefit them.

Research who is actively making a real impact in your field of interest, not just those who claim to be for the sake of public image, but those whose work shows real substance. Doing this requires a blend of discernment, critical thinking, and open-mindedness. Don’t just assume someone is impactful because they say they are; evaluate thoughtfully, stay open to unexpected sources, and think for yourself. Reach out to individuals whose involvement you believe could strengthen your efforts or advance the field, even if they come from outside of it. Sometimes meaningful contributions come from unexpected places.

You never really know who will respond until you put yourself out there. Based on how they presented themselves publicly, I’ve reached out to individuals and organizations I thought had aligned interests, only to discover they cared more about optics. They prioritized the outward appearance of supporting important issues like awareness, resource development, and research, but were actually motivated by self-interest and how their involvement made them look, rather than by a genuine commitment to the work and producing results to benefit society. At the same time, I’ve been surprised by people I never expected to hear back from. That’s why it’s important to keep reaching out with authenticity and clarity.

People are complex, and silence or rejection isn’t always personal. If it is, that’s okay. It likely means that person or organization is not the right fit for you. When you are starting off misaligned, chances are it will not get better. Not every opportunity will come to fruition, sometimes due to factors beyond your control. So focus on what you can control: honing your skills, expanding your knowledge, clearly explaining why collaboration would be mutually beneficial, and showing respect in how you approach others. Let your consistent efforts and body of work speak for themselves.

Even in professional settings, everyone is just trying to figure things out. I believe it is important to bring humanity back into communication, even in professional conversations. People often get caught up trying to present an image of perfection to ensure success, but many things are arbitrary and beyond our control. I believe the best approach is to simply do your best, avoid overthinking, and reach out with authenticity and clarity. That way, you improve your chances, and when a connection does happen, it’s built on a genuine and more sustainable foundation.

Contact Info:

- Website: Sierra’s Website: https://sierradomb.com

- LinkedIn: Sierra’s LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/sierradomb/

- Other: Visual Snow Initiative Website (Nonprofit Organization): https://www.visualsnowinitiative.org

Image Credits

TEDx

University of Miami

Visual Snow Initiative