Today we’d like to introduce you to Cody Harrison.

Cody, can you briefly walk us through your story – how you started and how you got to where you are today.

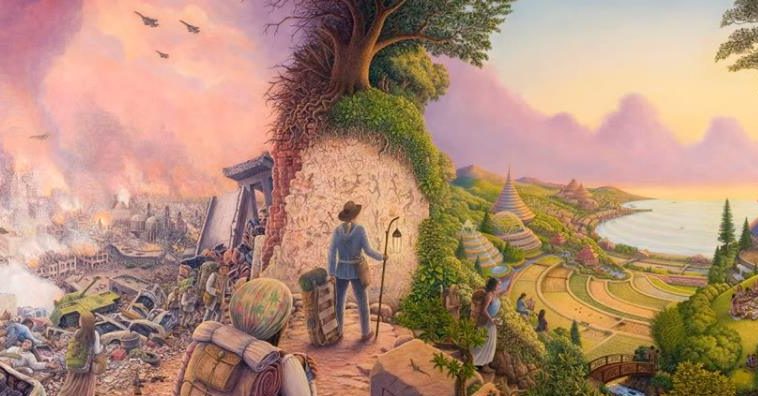

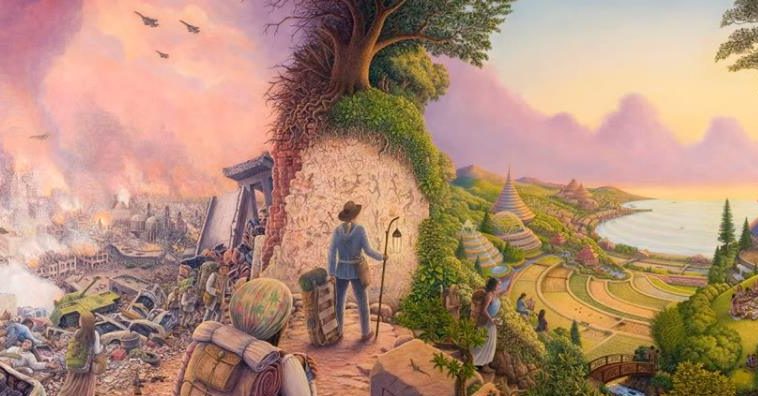

Unless we’re going to go all the way back to the “final project” I did on Inventorship in 6th grade, then I think my professional story begins with a trip to Africa during my sophomore year at Duke for a safari with my family. We went through an organization called AIM which allowed my parents to get some continuing education credits out of the trip by visiting a private hospital in Nairobi as well as a “hospital”, if you can even call it that, in a rural area. The inequality was striking to say the least.. That experience plus that of driving by the vast slums of Nairobi in our wonderfully air-conditioned Land Rover planted a seed in me. I didn’t know it at the time, but probably 4 months later it led to an epiphany during a car ride back to Duke after spring break in Costa Rica. That epiphany was first of all that it is absolutely unacceptable to me that we have not chosen to provide the basic human necessities to every person on the planet. We have the resources, we should do it, period. I decided at that moment that I had no interest in working on any job or project that wasn’t at least tangentially related to food, water, energy, housing, healthcare, or education.

This epiphany began a fervent period of research into all things sustainability, I ate up absolutely everything I could on the subject. Early on I was particularly interested in high tech solutions like graphene and synthetic biology, maglev wind turbines and shotcrete monolithic dome houses, all of which as a 20-year-old guy had a certain excitement and draw to them (over time I realized I put high tech on a bit of a pedestal). The first thing I came across that I actually attempted to work on professionally was maglev vertical axis wind turbines. I saw a sensationalized ad by a group in China about a large maglev turbine that they claimed could replace ~500 avg. horizontal turbines, could power over 100,000 homes, and operated at a lower speed and thus risk of bird death and noise pollution.

It drew my attention to say the least and I found a group in Arizona working on it. After a bit of back and forth, we decided we would attempt a JV to commercialize the technology. At this point, the pragmatist in me said that I should probably speak with an attorney. Here Duke came through and I found a JD candidate named Casein Gregg who was a great resource for me throughout the years. He suggested I form an LLC to protect myself from legal liability, so I did and my company Corona Enterprises was born. At the same time, I began looking into which departments at Duke might be interested in such a venture. I spoke with Barry Myers at the Duke Center for Entrepreneurship and Research Commercialization and the Duke Translational Research Institute who unfortunately couldn’t answer my questions but forwarded me to a woman whose name I will leave out who never responded to me even after multiple follow-up emails. I attempted to speak with a couple other departments at Duke and people were interested but I found no real paths to DO anything. Maybe if I was more experienced or talked to different people (or followed up that one last time necessary) I would have been able to figure out how to get a University to engage in a project.

After this first failure, I decided I would do more legwork the next time before trying to bring in Duke. I began to hatch a larger plan inspired by two technology platforms I had come across in my research. The first was an interesting system utilizing a genetically enhanced bacteria housed within in a microbial fuel cell to turn the organic contaminants in wastewater into electricity, biogas, and useful chemicals such as isoprene (which can be used to make a synthetic rubber), created by a company called Pills Energy. Again. Clearly very high tech and with tremendous potential – but fairly juvenile in its development, it was only at the lab scale. The second was a set of open source machines called the Global Village Construction Set (GVCS) being developed by a non-profit called Open Source Ecology. Fifty foundational machines that in theory could be used to make the entire rest of the human technology tree. Everything from tractors, to wind turbines, to steam engines, to gasifiers, to well-drilling rigs, to welders, to circuit boards, to bio-plastics extruders, to bread ovens, all at a fraction of the cost of industry standards and designed without planned obsolescence or non-standardized parts. A life-size Lego set to build a sustainable world. In other words, the open sourcing of the means of production, which as I saw it would go down in history as a landmark achievement of humanity.

Next, I began developing a business plan that would incorporate the GVCS and the Pills Energy “electrogenic bioreactor” as the centerpieces in what I imagined as a landscape scale version of a home energy audit, with North Carolina swine farms being the first target market for deployment. There were a few reasons for this. #1 Legislation in NC seemed to be incentivizing it (they had recently outlawed construction of new waste lagoons and .7% of the state’s electricity was required to come from swine waste by 2020 per NC’s Renewable Portfolio Standard, however, this got pushed back multiple times due to the lack of viable proposals). #2 because the swine waste is high energy fuel and it is already collected in a lagoon waiting to be used, but instead is wafting cancerous fumes toward the neighbors. #3 because they spray the waste on fields contaminating them (and areas downstream) such that only crops not intended for human consumption can be grown there. #4 I envisioned a scalable process whereby a Pilus EBR mounted on a semi-trailer would be parked at a given farm where it would begin processing the waste in the lagoon while producing electricity and/or biogas that could be utilized to decrease the operating costs of the farm. Once the lagoon waste had been dealt with the mobile unit could move to the next farm and a smaller stationary system could be installed to deal with the day-to-day waste of the farm. Given that I was a student I thought that the likelihood I would be able to raise the funds necessary to pull this off were slim, but I knew it would be a good process to go through nonetheless. I also knew that if I were to pull it off I would need some help, and began to recruit additional brains to the endeavor. Unfortunately, I was completely unsuccessful in bringing anyone competent, or otherwise, onboard in any significant capacity, and met obstacle after obstacle in making this idea a reality, chief among them were the facts that the Pilus technology and the GVCS were still in their infancy and not ready for the type of deployment that I envisioned.

Luckily, Jason Barkeloo, the founder and one of the inventors of the Pilus Energy technology saw something in my two-year perseverance in trying to bring his technology to market and upon graduation from Duke offered to bring me on as the first “employee” at Pilus Energy (working as an independent contractor through my LLC). My task was simple on paper, Jason wished to leverage my abilities to help the company further develop products, intellectual property, prototypes, and pilot programs. Jason also wanted to begin the process of licensing its technologies and hired me to support licensees with the deployment of the technology. However, I struggled to attend to those directives given the technology was still at the bench top scale, the company was unfunded, and the marketing materials were sorely in need of an update. So I set out to address the issues that could be addressed at the lowest cost. Based on my assessment those were the website and other marketing materials, and lack of public awareness of the company. In the process, I ran a campaign on Indiegogo to try to raise some money and while only raising $10k of $50k goal we got a number of pieces of good press, some much-needed public awareness and yada yada yada a month later the paperwork for an acquisition by Tauriga Sciences, Inc. had been inked. Technically it was a reverse triangle merger whatever the hell that means. In theory, this was going to give us some funding to move forward and we began so we established a third-party utilization contract with the EPA to use a Testing & Evaluation facility they have in Cincinnati at the municipal wastewater treatment plant to begin to commercialize the technology. Unfortunately, Tauriga did not have enough cash to fund the full $1.8M budget so we sat down with a state funding agency called Third Frontier to interview for a $1M loan but we didn’t get it.

Sadly, after that, I wasn’t included in fundraising efforts and I just focused on managing the company. Over the course of the next 10-12 months I spent about $200k of Tauriga’s money and assembled a team of around 40 contractors, with about 10 being supplied by the GC of the Testing and Evaluation facility, Chicago Bridge & Iron. We did the best we could to develop the technology and were able to move the IP forward a bit, generate some data, and learn more about microbial fuel cells but couldn’t get an MVP. I look back and still wonder what we could have done better. I think the major mistake that was made was there never came a point where someone said, “ok we’re not going to be able to raise the full $1.8M, we need to reassess and come up with a new budget.” If I had known the money wasn’t coming maybe we could have pivoted to get to a different MVP. In this case, even hindsight is not 20/20 and I really don’t know. At the 13-month mark Tauriga told me they couldn’t afford (subtext: didn’t want to) pay me anymore, we parted ways. I still consider it without a doubt my greatest failure so far in life. I’ll lead a lucky life if it remains my biggest I suppose, but I can’t help but feel sad about it given the immense beneficial social impact the technology could have out in the world.

After the engagement with Tauriga ended rather abruptly and without much warning, I was left wondering what to do next. I quickly learned the lesson of one of the downsides of being a contractor and owning your own business: without income, the expenses start to drain the coffers rapidly. I just as quickly decided to try to get out of my apartment lease as well, feeling that I didn’t need something that nice anyway and found a friend who was more than happy to take it over. I found a cheaper place that was month to month, which was perfect since I had little reason (my girlfriend was ready to get out too) to stay in Cincinnati any longer without Pilus to work on and began looking for a new gig. I found a local worker-owned cooperative called Sustainergy doing energy efficiency work through a local non-profit called Green Umbrella that posts sustainability-related jobs. They were looking for an insulation and air sealing technician, which I wasn’t interested in but their whole schtick was right up my alley so I met up with the guy who started it, Flequer Vera to talk. Flequer and I hit it off and decided we would work together. I started going to Sustainergy board meetings and he put me in touch with Empower Gas & Electric one of their partners who was hiring energy assessors which I could easily learn how to do given my basic understanding of building science. Over the course of ~6 months, Corona completed more than 200 assessments, sold around two dozen energy efficiency upgrades, and for the first time created a tangible reduction of environmental harm on the environment and improvement to human health and well-being.

While enjoying the energy efficiency work quite a bit, I was still looking to move out of Cincinnati, probably closer to the west coast which felt like home and seemed likely to have far more opportunities in the sustainability space. After a series of unfortunate events that started with that month to month place I was renting having bed bugs and ended with me hunting them down around my girlfriend’s bed in the middle of the night, I bought a tiny house on wheels. With a little help, I outfitted it with electricity and running water and found a friend out in Southern California with space and a willingness to let us park a legally grey zone tiny house. He was also open to the idea of building an ultra-green house on the property and I figured it would be a great location for my Open Sourcing the Living Building Challenge project. By April we were waving Cincy goodbye headed for some of the best weather in the world. After spending a little over a year and a half finishing out the tiny house and building a fresh client base/network out here Corona now has a handful of small clients/projects in California. 1. Helping to build an online sustainability marketplace at coneybearecleantech.com 2. Acting as Project Manager for a $750k grant-project being administered by Tree San Diego and funded by CalFire 3. Working pro-bono with Seed Consulting Group to provide management consulting services to high-quality clients such as Caltech 4. On the side trying to test out a strain of bacteria that has been shown in the literature to facilitate similar chemical reactions as those that form limestone (which is a carbon sequestering process). I’d like to combine these bacteria with hempcrete and 3D printing to create high-performance houses made from local materials that are carbon negative, all of which ties into the open source the LBC project.

We’d love to hear more about your business.

Well, Corona is a sustainability consultancy. It is lean, no employees just contractors. It tries to act as a regenerative design-build company, creating plans for environmental regeneration and then implementing them. Unfortunately, not as much of that happens as we would all like. What pays the bills is project management, business development (i.e. sales), stakeholder engagement, and communications/marketing/branding, but all for organizations involved in the sustainability space. What sets us apart is that we are at the cutting edge of the sustainability space, which is a frustrating label because the cutting edge is way beyond “sustainability”. We have done so much damage to the environment it isn’t enough to sustain the natural capital we have left, we have got to regenerate some of what has been lost or we are in big trouble.

What were you like growing up?

Haha. Hmmm. How much detail to go into here…. A little bit too much energy at times. Enjoyed playing games and goofing off whenever possible. Went to a Montessori school through 6th grade and probably spent a lot more time pestering girls and hanging with friends than studying anything. Enjoyed sports, tennis, basketball, soccer etc. Did not enjoy skiing because I was forced to go every Saturday in the winter, now I love it though. Didn’t really develop many interests besides goofing off and girls until college.

Contact Info:

- Website: www.corona-enterprises.com

- Phone: 434-242-6879

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/CoronaEnterprises/, www.facebook.com/thetiniesthouse, www.facebook.com/oslbc, www.facebook.com/trejuvenation

- Other: www.coneybearecleantech.com/marketplace/products

Getting in touch: VoyageLA is built on recommendations from the community; it’s how we uncover hidden gems, so if you know someone who deserves recognition please let us know here.