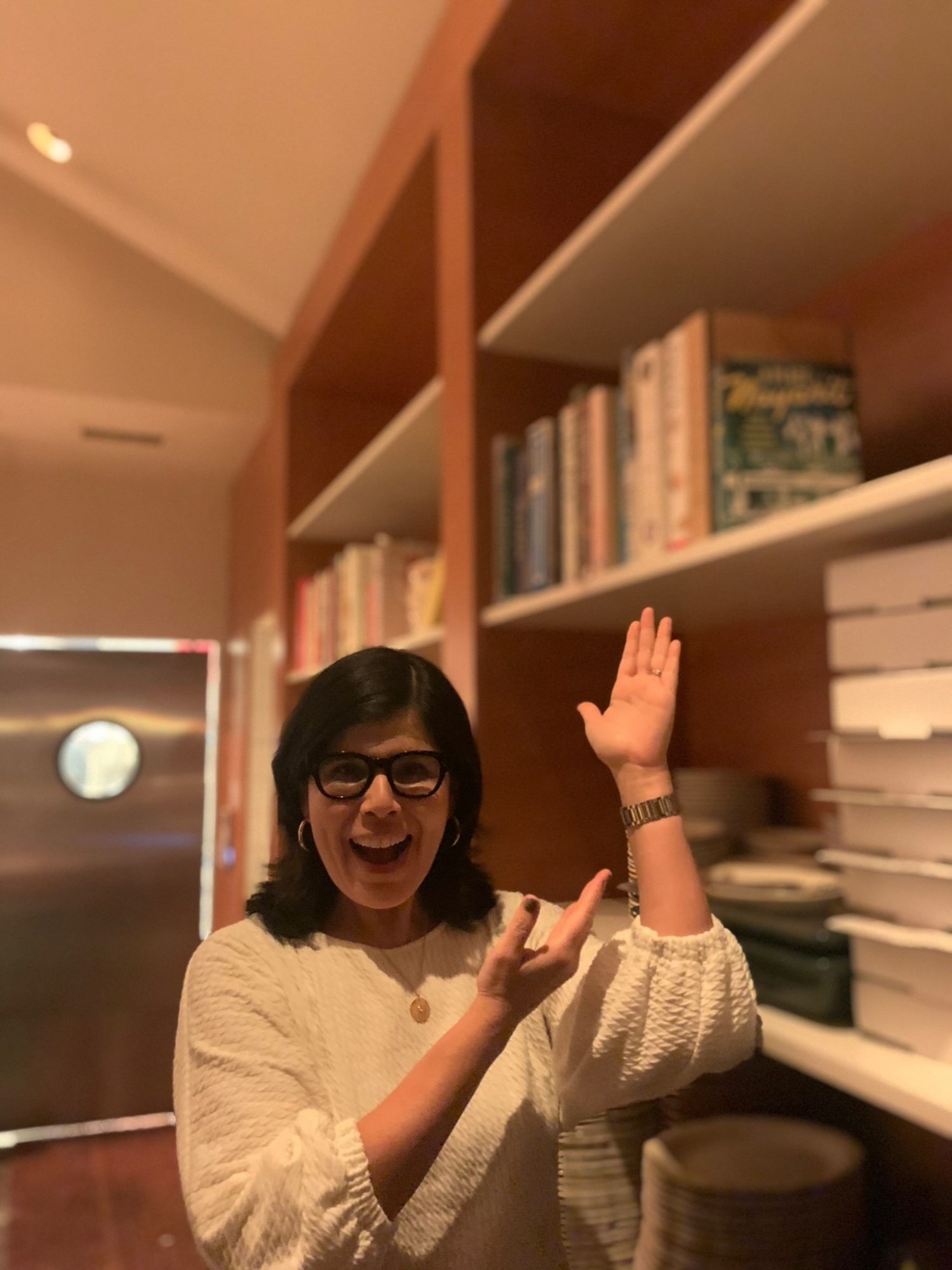

Today we’d like to introduce you to Natalia Molina.

Hi Natalia, can you start by introducing yourself? We’d love to learn more about how you got to where you are today?

I went to UCLA. Like a lot of people who are first gen, my family had told me, “Be a doctor, be a lawyer.” I didn’t really know there was anything else. But after I took a biology class and a calculus class, I promptly realized I was not going to be a doctor. I liked the storytelling of history or anthropology, and at first, I thought: I will get a master’s in urban planning and work at City Hall. But professors started talking to me, saying, “You should be a professor.” And I said, “How does one do that?” They said, “There’s this thing called the graduate degree. You get a PhD.” And the kindness of those professors! They helped me learn the ropes, step by step, and there were a lot of stumbles along the way, but what I learned to do was ask for help.

I had to write a senior thesis for my history class, and I was interested in how the East Los Angeles freeway was built because it ended up dividing parts of East LA, like Boyle Heights. Residents protested it, and I had the petition with their addresses, so I decided to go interview them. I was walking down the street, looking for the addresses but then the addresses ended at the freeway. The homes had been razed. There had been a proposal for a Beverly Hills freeway too, but it never got built, because those residents had plenty of attorneys and plenty of money. And it was in that moment that I realized people in East LA had been trying to get people to listen to the reasons their communities mattered, and I wanted to help tell stories like theirs.

Can you talk to us a bit about the challenges and lessons you’ve learned along the way. Looking back would you say it’s been easy or smooth in retrospect?

I wrote A Place at the Nayarit about my grandmother, but I never met her. As a historian, it can be challenging to find the stories of people like her—people who are, as I like to call them, “under-documented.” How do you tell the story of someone you’ve never met from a time before you were born? I did oral interviews. I looked through the archives. I went to libraries. I read newspapers from the 1950s and ’60s, but I wasn’t really finding many of the Mexicans and Mexican Americans who went to and worked at the restaurant. And then it hit me one day. I remember my Tia Chayo sitting on her porch reading El Eco de Nayarit, the hometown paper of her state of Nayarit. And it was by doing archival research in Mexico, where I traveled to read all the papers from El Eco de Nayarit, that I found the people who had moved to LA from the state of Nayarit in the 1950s and ‘60s, in the heyday of the restaurant. Many were there because of my grandmother’s help immigrating them and giving them jobs; others were customers at the restaurant. My grandmother was interviewed in the paper and advertised there. So we think that because we’re studying a place, we should understand the sources from that place. But what I learned in writing the book is we must understand people’s attachments and especially if you’re telling immigrant stories, that can mean attachments to where they’re from. For my grandmother, Nayarit was meaningful, so she stayed tethered to it.

Can you tell our readers more about what you do and what you think sets you apart from others?

I’m a professor at USC, University of Southern California. My passion is always to help people understand why we think about race the way that we do and how that’s changed over different historical time periods. I do that through my writing: A Place at the Nayarit: How a Mexican Restaurant Nourished a Community; How Race Is Made in America: Immigration, Citizenship, and the Historical Power of Racial Scripts: Fit to Be Citizens?: Public Health and Race in Los Angeles, 1879-1940. I also do that through my teaching: I teach classes in Latino Studies, in ethnic studies, in history. I always want people to understand how to connect across race and ethnicity, as they understand how many experiences they have in common.

Can you talk to us a bit about the role of luck?

I’m actually reading a book on gambling by Annie Duke, who says we underestimate the role of luck in our lives. But I think I’ve never underestimated the role of luck in my life. I came from a working-class area: I’m not just the first person to go to college in my family—I’m the first person to go to college in my neighborhood. That happened in part because I’ve always loved to read, and I just wanted to know more. But I was also lucky. The luck is my local college was UCLA. The luck is that when I went to talk to my professors, they wanted to guide me. Luck can’t find you if you don’t show up, so you must show up.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://nataliamolinaphd.com/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/prof_nataliam/

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/Prof_NataliaM