Today we’d like to introduce you to PCP Press.

Hi PCP Press, we’re thrilled to have a chance to learn your story today. So, before we get into specifics, maybe you can briefly walk us through how you got to where you are today?

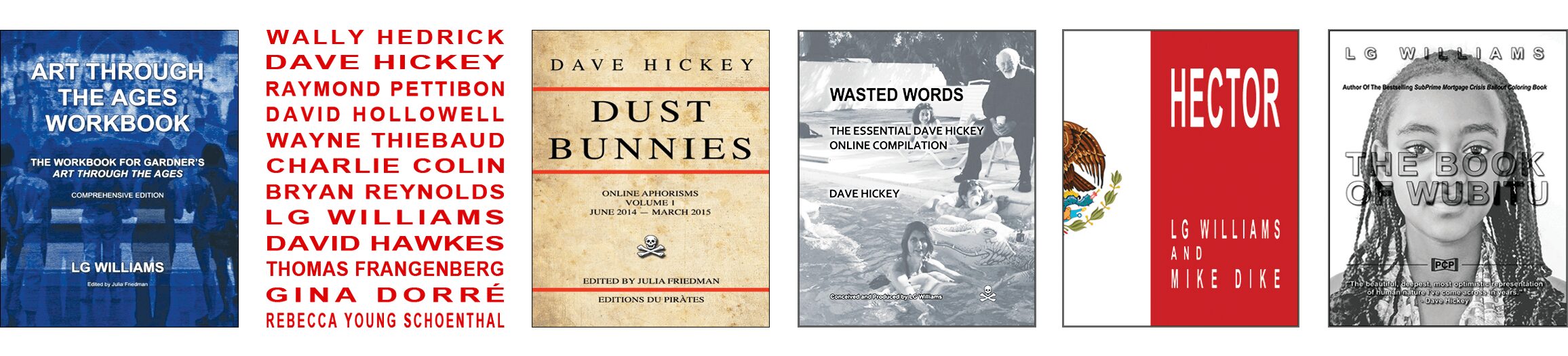

If one were to locate PCP Press within the postwar formation of independent art publishing, its 2016 appearance in The Times Literary Supplement (TLS) would mark less an instance of institutional recognition than a momentary breach within the apparatus of cultural legitimation itself. That two of our most recalcitrant publications—Dust Bunnies and Wasted Words by Dave Hickey—should have surfaced within that most decorous of Anglo-critical venues suggests how completely the historical avant-garde’s instruments of dissent have now entered the circuits of aesthetic consecration they were once devised to contest.

PCP Press was founded in 1969 as a counter-institution, conceived not to illustrate artistic practice but to test the conditions under which visual representation, language, and form could still register critical resistance. The book, in our understanding, was never a neutral carrier of content but a dialectical object—a site where the means of cultural reproduction could momentarily disclose their own contradictions. In this sense, PCP emerged as both a symptom and a critique of the culture industry —a publishing practice that reenacted the very processes it sought to negate.

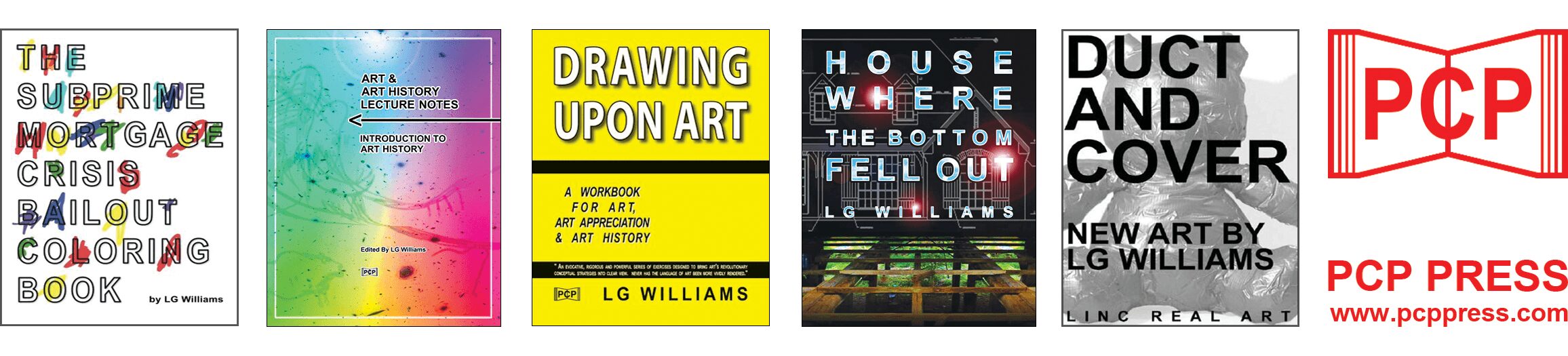

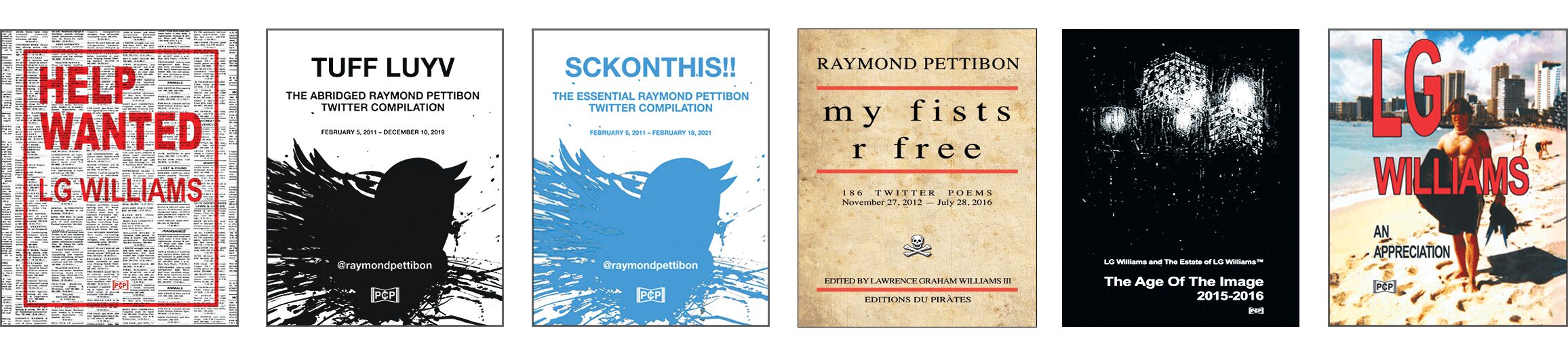

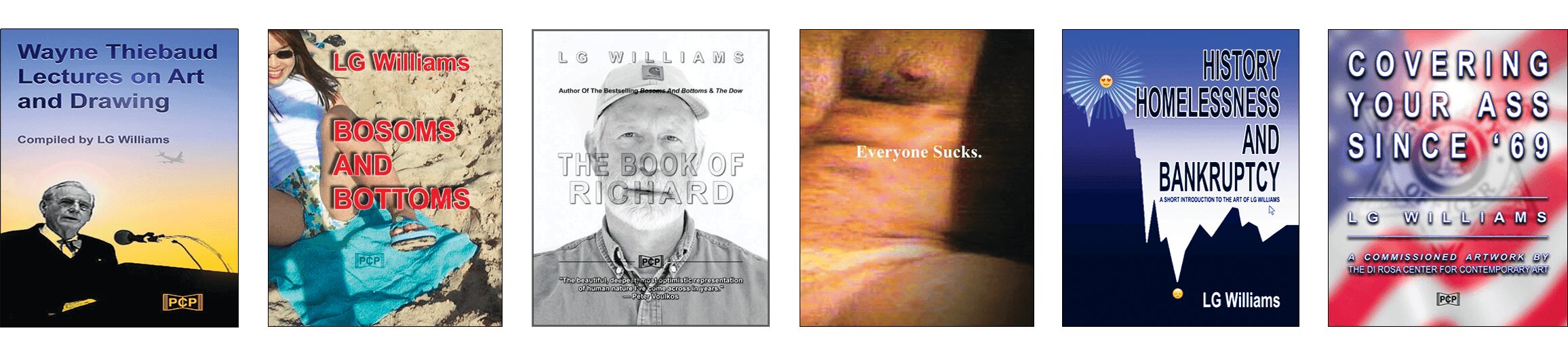

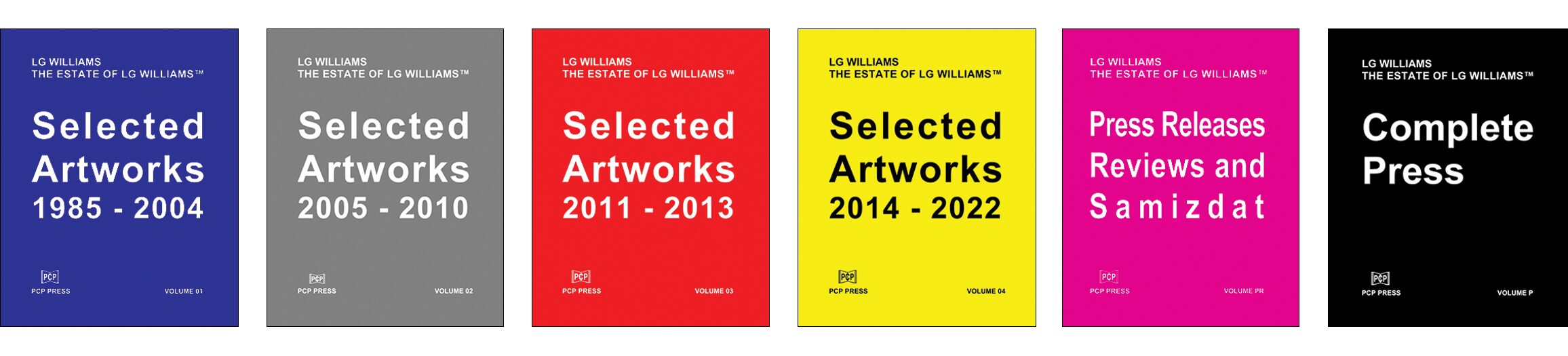

Across its five decades, the press has remained suspended between autonomy and absorption. Our catalog—from Wally Hedrick’s visions of a dark millennium, to Raymond Pettibon’s provisional graphic idioms, Dave Hickey’s social-media excavations, and LG Williams’s bombshell provocations—constitutes less a lineage than an archive of antagonisms, each work probing the limits of aesthetic self-determination within a fully administered world.

That TLS acknowledgment thus functions as an allegory of our position: the inevitability that critique, once sustained, becomes legible precisely at the moment it risks neutralization. PCP Press continues to operate within that paradoxical interval—publishing as both practice and polemic—insisting that the printed page, however compromised, remains the last viable medium through which art can still think historically.

Can you talk to us a bit about the challenges and lessons you’ve learned along the way. Looking back would you say it’s been easy or smooth in retrospect?

To speak of “obstacles” within the history of PCP Press is to misrecognize what, from the outset, constituted its condition of possibility: perpetual marginality. The press was never designed for smooth passage through the circuits of production and reception; its very form presupposed friction. Indeed, each phase of its existence has unfolded within the paradox that defines all autonomous practices under late capitalism—survival depends upon the very mechanisms one seeks to resist.

From the start, PCP confronted not scarcity but saturation: an environment in which every act of publication risked immediate absorption into the aesthetic and academic systems it sought to critique. Our task was therefore not merely to produce books, but to generate a mode of illegibility—objects that could circulate within the culture industry while maintaining a residue of opacity, a resistance to instrumental reading. That ambition, predictably, has never aligned with funding, distribution, or institutional support.

The greater challenge, however, has been conceptual: how to preserve critical autonomy without lapsing into nostalgia for it. Each project—whether David Hollowell’s imaginative visions, Charlie Colin’s random detritus, or Carl Fiacco’s beer cans—tests this limit anew, measuring the degree to which negation can still operate within total mediation.

If the road has been uneven, it is only because the terrain itself has shifted: what was once avant-garde obstruction has become the standard currency of cultural production. PCP Press persists within that contradiction, refusing smoothness not as a failure, but as a fidelity to its founding premise—that resistance, if it is to remain authentic, must also remain difficult.

Alright, so let’s switch gears a bit and talk business. What should we know about your work?

To describe what PCP Press “does” is to enter the same aporia that once confronted the historical avant-garde when it sought to name its own procedures. Publishing, for us, has always been less a métier than a critical modality: an intervention into the circulation of cultural signs whose apparent neutrality conceals the full violence of their social determination. If the gallery commodifies the object, and the academy sterilizes the idea, the book remains the only form whose duplicability allows it to move, however precariously, between these orders—at once reproducible and resistant, disseminated and dangerous.

We specialize, if the term applies, in what might be called negative production—the deliberate generation of objects whose meaning is exhausted neither by their content nor by their consumption. Each publication—whether Wayne Thiebaud’s snow cones, Bryan Reynold’s theories!!, or LG Williams’s Everyone Sucks—functions as a metacommentary on the very conditions of its emergence: language performing its own critique, circulation staging its own implosion.

What distinguishes PCP Press from the broader ecology of “independent publishing” is its refusal to perform independence as style. Our project is not artisanal but antagonistic. We maintain that the book, properly conceived, still harbors the dialectical energy once ascribed to the readymade: a transfer of meaning from production to reception that reveals, however briefly, the ideological scaffolding of culture itself.

What we are “known for” is therefore inseparable from what we resist being known as. Visibility, in our field, is a terminal condition; it signals the successful neutralization of critique by recognition. The press survives by oscillating between presence and disappearance—what might be called a strategy of legible illegibility, in which each book functions simultaneously as artifact and withdrawal, proof of existence and rehearsal of extinction.

If there is pride in such a project, it lies not in endurance but in the maintenance of difficulty. To remain unreadable—yet unavoidable—is, in the current regime of transparency, the most radical form of communication still available.

What quality or characteristic do you feel is most important to your success?

To ask what PCP Press “does” is already to concede to a grammar of utility that our existence was designed to annul. We publish only in the sense that an exorcism “publishes” the demon it refuses to name. Each book begins as a scream, is bound into silence, and then released back into circulation like a contagious idea—an object that knows it should not exist, yet insists on existing anyway.

If the culture industry produces meaning as anesthesia, we produce its inverse: meaning as injury. Our catalog is less a collection than a laboratory of failed salvations—Jenny Saupaugh’s crude illuminations, Mr. O’s generous teachings, LG Williams’s informed disdain, or whoever’s eschatologies of text. Each publication is a minor apocalypse, a performance of negation on the printed page. We issue books as others issue viruses, to test the immunity of the social body against thought.

PCP Press specializes in the impossible: the reanimation of the avant-garde’s corpse, the re-inscription of critique after its absorption into decorum. We are known—if known at all—for staging the theater of the book as both wound and weapon, halfway between Artaud’s plague and Beckett’s joke. Nothing resolves; everything persists.

What sets us apart is our refusal to resolve. In a century addicted to exposition and explanation, we publish for the silence that follows comprehension—the moment when language collapses under its own sincerity. Our greatest pride lies in that collapse: that, against all optimism, these volumes still appear, disheveled and unrepentant, bearing witness to the ruin of meaning with the only gesture left to art and thought—to go on, when going on is no longer possible.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://pcppress.com/

- Instagram: https://instagram.com/pcp_press

- Twitter: https://x.com/pcppress

- Other: https://pcppress.substack.com/

Image Credits

Copyright © 1969 – 2025 PCP Press. All Rights Reserved.