Today we’d like to introduce you to Jessica Kim.

Hi Jessica, thanks for sharing your story with us. To start, maybe you can tell our readers some of your backstory.

To usher in the new year, I recently wrote letters to my eight-year-old self and my twenty-eight-year-old self. It was an odd experience because I told my past self that I would venture into the unexpected by discovering poetry in high school while I told my future self never to forget this craft. While I only started writing poetry at fifteen, I was always amid the wonders that language could offer. Growing up in a bilingual household where I learned Korean before English and moving across countries and continents multiple times, I exist at the confluence of languages. I also grew up with a family who pried open my love for math and later computer programming, which transcended the cultural definition of language and introduced me to the secrets of a technological world. I like to believe that my love for language in its multidimensional forms eventually led me to poetry.

I was drawn to poetry because of its versatility. I could explore my immigrant and disabled identities, write about social issues larger than myself, and also focus on small and routined moments. I admire this art form because it’s magnanimous—it welcomes all my experiences and gives me the tools for experimentation and innovation. Many of my poems are multilingual, meddling with hangul homonyms or the act (and limits) of translation. Beyond poetry on the page, I’ve also explored communal spoken-word performances as the West Regional Youth Poet Laureate, created my first film in response to a poem I wrote, used HTML syntax to design code poems on Twine, and collaborated with visual artists to host an interactive “edible” poetry workshop. Poetry gives me the space for dialogue, and in the process of collaborating on interdisciplinary poems, I think I’m able to unite these various forms of languages with the common purpose of communicating and connecting.

I promised my future self that I will always be a poet at heart, whether I’m writing, programming, or doing something completely unimagined in the next ten years. I recognize that my newfound identity as an artist will not weather away as long as I approach the world with the same spirit of curiosity, innovation, and joy as I do when I start writing a new poem.

Can you talk to us a bit about the challenges and lessons you’ve learned along the way. Looking back would you say it’s been easy or smooth in retrospect?

As much as poetry offers a space for selfhood, I was apprehensive about putting forth my visual impairment in my poems because the disability narrative was absent in the literary community, especially among young writers. Like many writers going into the publishing industry, I was juggling the weight of interiority and publicity—is trauma meant to be glamorized and commoditized in order to be a writer? I wanted to be authentic in my craft, yet I was always constantly tuning my writing to the mainstream audience. Would these people understand what it means to be vision-impaired? Did I even have the authority to narrate the disability experience?

When I first published a poem about my disability in a literary magazine, I was met with solidarity. A teen poet reached out to me saying that they had never seen a young writer write about disability and that it inspired them to examine a new part of their identity. For the first time, my story mattered. Conversations like these empowered me to put “disabled” in my third-person biographies and eventually write my book, L(EYE)GHT, about the intersections between immigration and visual impairment. Now being vision-impaired is something so fundamental to my identity and my Persona as an artist, but being public about this wasn’t always something I had the courage to do, and embracing myself and the literary world was definitely a struggle.

As you know, we’re big fans of you and your work. For our readers who might not be as familiar what can you tell them about what you do?

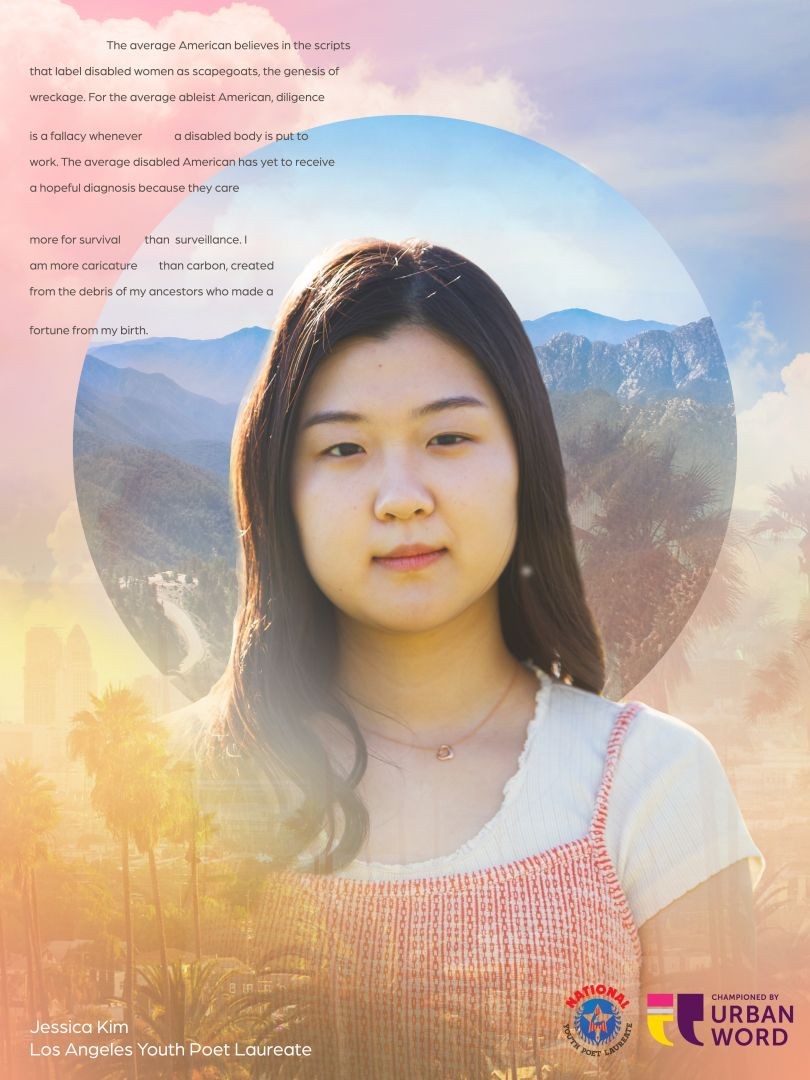

It’s so exciting yet frightening to call myself a writer. I am just eighteen, I’m still a student in high school, and a lot of times I don’t really know what I’m doing with my life. That said, being a poet means community and joy, and everything I do embodies that. I’m the 2021-2022 Los Angeles Youth Poet Laureate, current West Regional Youth Poet Laureate, and the runner-up for the national title. That means many of my poems honor different communities, especially in Los Angeles, such as young writers, Asian writers, and disabled writers. On many weekends I stand on Slam stages or in libraries, reading my work or teaching poetry workshops in collaboration with organizations like Beyond Baroque, the Los Angeles Public Library, and WriteGirl LA. Every time I find a unique group of people with distinctly different lived experiences bonded by a shared passion for storytelling—I find joy, and the community finds me.

Although a lot of my recent work has been geared toward collaborative settings, I started as a writer who published her work in online literary magazines, which Intuitively feels more solitary. But seeing my poems like “Broken Abecedarian for America” in Frontier Poetry and “Wavelength // Waveless” in POETRY Foundation’s Magazine and having so many writers reach out to me about my work, I’ve come to understand that poetry is inherently conversational and communal. It’s impossible to separate the collective from the personal in my writing, and therefore, I am dedicated to the liminal space where each individual can feel heard.

Being a writer means so much more than showcasing my own poetry. It means celebrating the voices of others. When I’m not writing, I edit for The Lumiere Review, a youth-led magazine focused on publishing counterstories—writing and art by marginalized creatives. In addition to the quarterly issues we publish, we are currently fighting against “-isms,” “-phobias,” inequality of all forms, environmental crises, physical and mental health issues, and humanitarian crises through our JUSTICE Collective. Each story we publish contributes to our donation efforts to organizations in Ukraine. Just this month, Lumiere became a paying publication, which I’m ecstatic about. I wanted to run a magazine to give opportunities for more people to publish their stories, and it’s very fulfilling to see that this dream is becoming a reality. How amazing is it to build community and find so much joy in doing so?

What was your favorite childhood memory?

I really liked mazes as a kid. It started with the mazes on Kids Menus at Olive Garden or Buca di Beppo, then I challenged myself to harder mazes in workbooks and eventually started drawing mazes of my own. My favorite childhood memory is sitting at my little crafts table in my family’s living room and building worlds on my own. While it’s been a long time since I’ve navigated through a paper maze, I’m still at the forefront of creation.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://jessicakimwrites.weebly.com/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/jessicakimwrites/

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/jessiicable

Image Credits

Image Credits

Travis Auclair (headshot)