Cory Bilicko shared their story and experiences with us recently and you can find our conversation below.

Hi Cory, thank you so much for taking time out of your busy day to share your story, experiences and insights with our readers. Let’s jump right in with an interesting one: Have you stood up for someone when it cost you something?

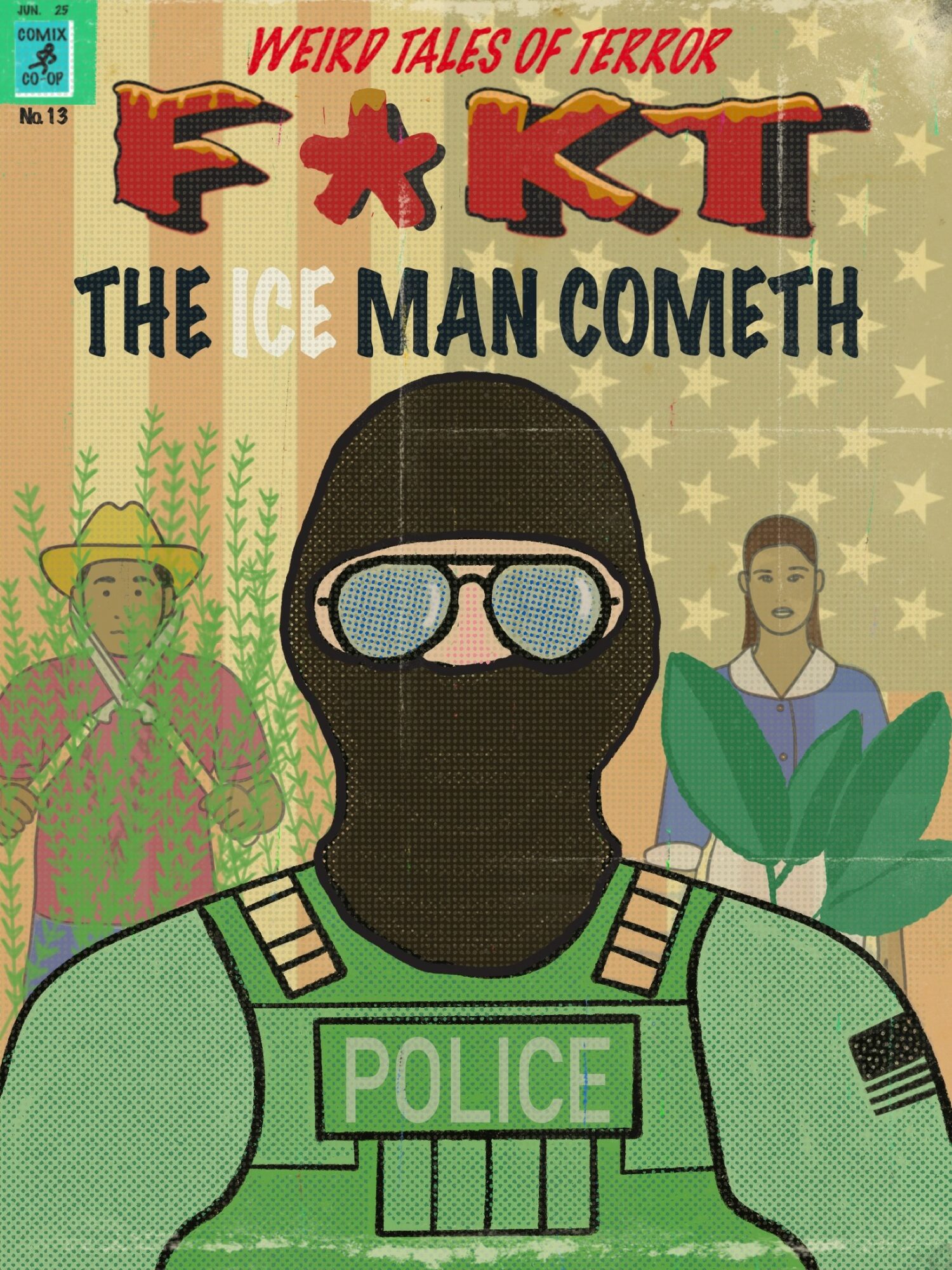

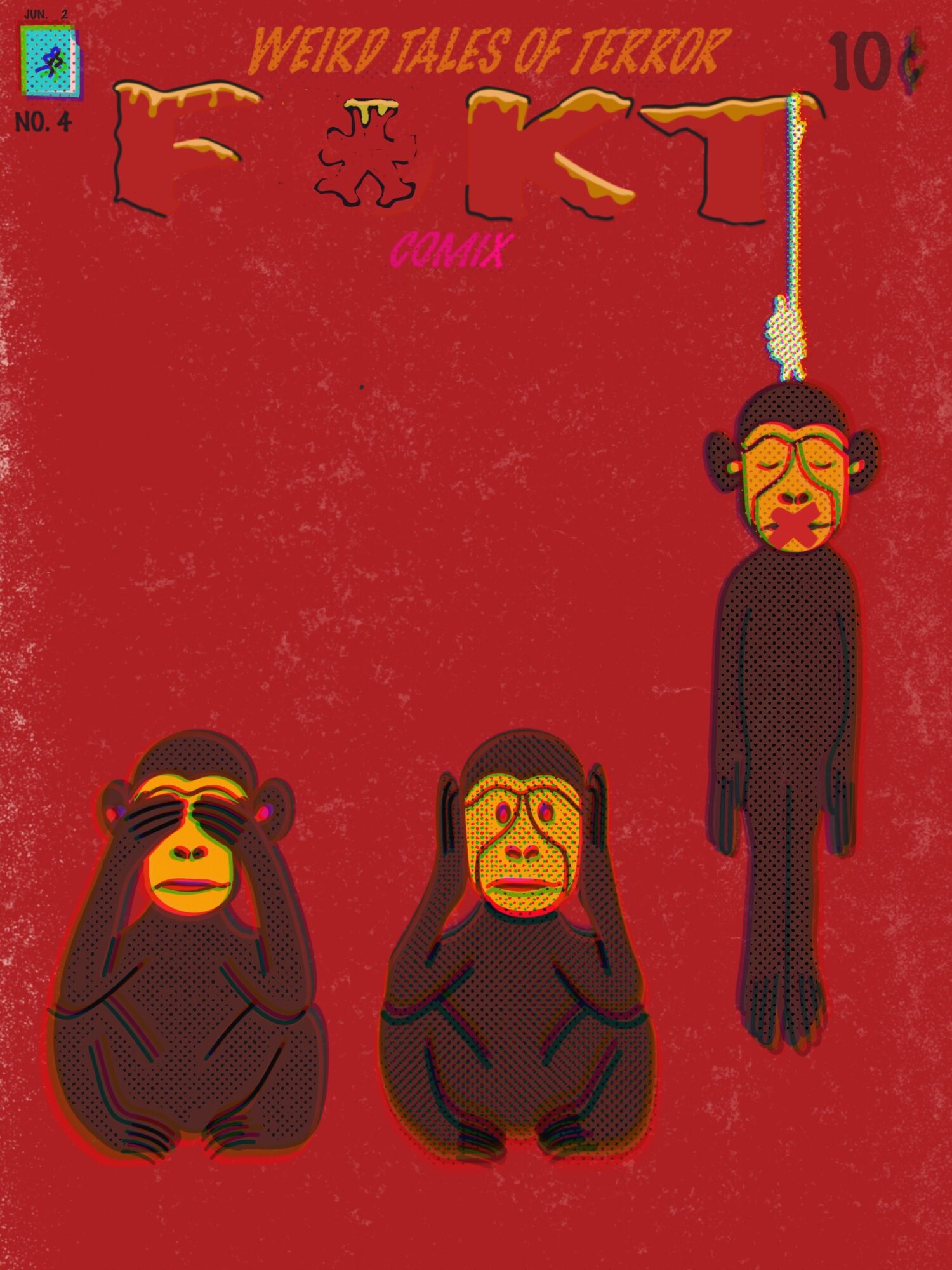

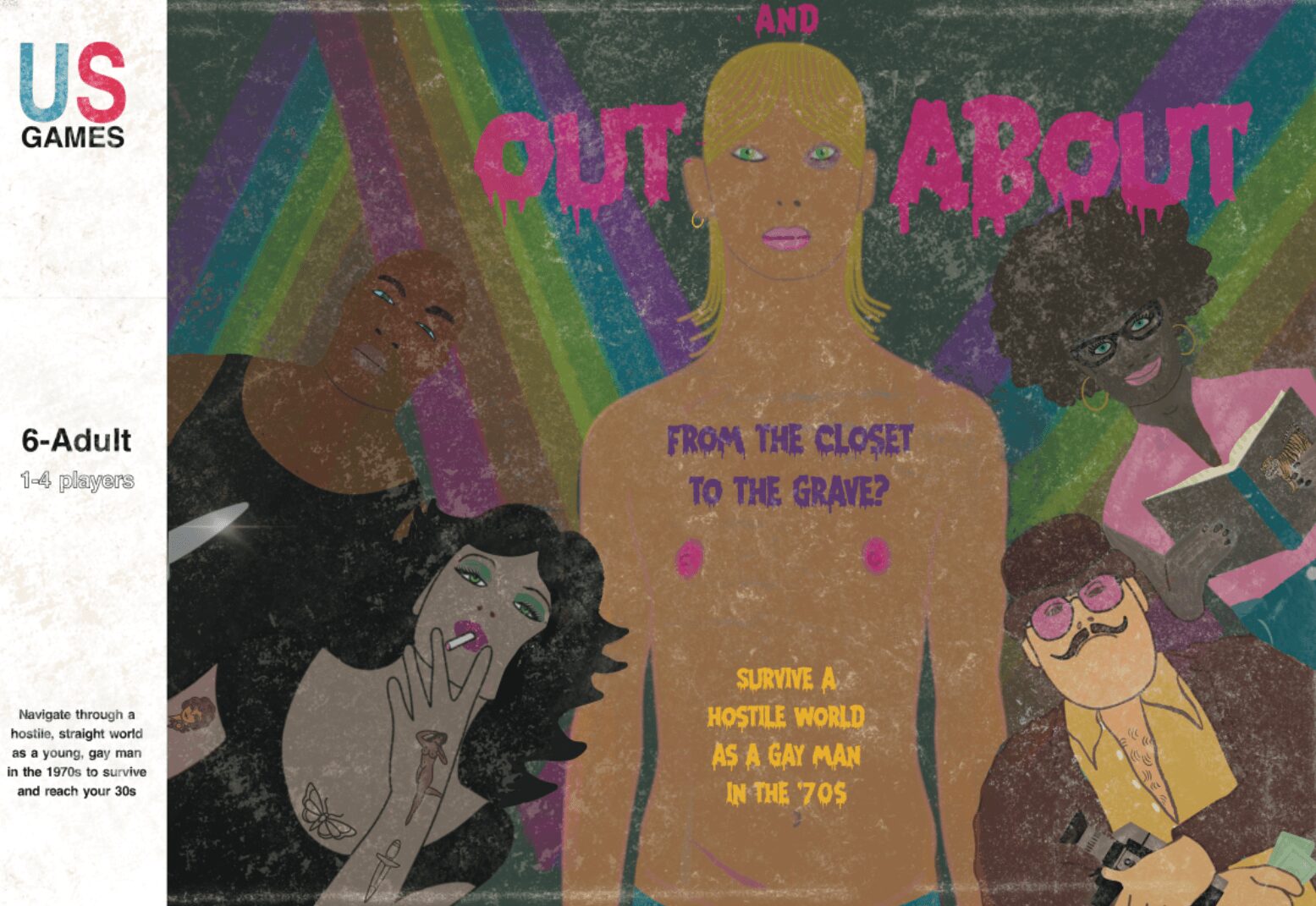

Well, I recently had several art pieces censored from a city-sponsored exhibit because they were deemed too politically charged. They were digital drawings that were critical of the current administration and the questionable actions of ICE agents. I’m not an immigrant, but I am appalled by much of ICE’s treatment of people, many of whom are harmless individuals trying to raise families. So, my standing up for them cost me exhibition space, but I don’t regret my choice at all. I will continue to speak up against what I see as unconscionable behavior.

Can you briefly introduce yourself and share what makes you or your brand unique?

My artistic practice is rooted in the excavation of memory—personal, cultural and inherited. As a self-taught visual artist working across mixed media, collage, painting and digital formats, I explore the complex relationships between nostalgia, identity and visibility. I am especially drawn to the stories that have been muted, fragmented or lost– what I refer to as the “ghosts” that linger within photographs, oral histories and cultural silences. Much of my work begins with found or vintage photos. These timeworn images, often anonymous or degraded, act as portals into the lives of those who came before us. Through layering, deconstruction and recomposition, I translate these fragments into new visual narratives– ones that honor the original subjects while inviting reinterpretation and reflection. The result is often haunting, but tender—where ambiguity becomes a form of truth. In recent years, I have expanded my practice into large-scale public art and socially engaged projects that bring community voices to the forefront. My work increasingly involves collaboration, particularly with underserved or intergenerational groups whose stories deserve a platform. For The Un‑Invisible Project in 2024, I mentored 35 members of the Long Beach Cambodian community, helping each to share a personal story through a visual art work and a written piece. The 70 works were then displayed in a traveling exhibit. Whether through murals or curated exhibits, my goal is to create visual spaces where overlooked identities become vividly present– where history is not just remembered, but reimagined.

Thanks for sharing that. Would love to go back in time and hear about how your past might have impacted who you are today. Who saw you clearly before you could see yourself?

My first “gallery space” was my grandmother’s refrigerator door, in Biloxi, Mississippi, in the early ’70s. When I was a kid, I loved to draw, but the only person who truly appreciated the drawings was my grandmother, whom my family and I affectionately call Maw-Maw. She would make such a fuss over them and then display them on her fridge with magnets in the form of different fruits. Whereas no one else seemed to care much for my creations, she made me believe in myself as an artist. I really think I wouldn’t be a professional artist who earns state and city arts grants and numerous opportunities if it weren’t for Maw-Maw’s undying support.

What have been the defining wounds of your life—and how have you healed them?

In 1999, my mom was killed in a car accident. I was a mess for quite a while, until I started making art in earnest, rather than as an occasional hobby. Not only did the act of creation seem to counteract some of the pain of mourning her sudden loss, but, in that art-making process, I was able to calm my mind and get in touch with my emotions. It put me into a meditative state that truly helped me. That’s when I saw the tremendously therapeutic power of art.

Next, maybe we can discuss some of your foundational philosophies and views? What’s a belief or project you’re committed to, no matter how long it takes?

Unfortunately, growing up in the deep South, I often heard racist and homophobic epithets that were tossed around thoughtfully. However, I also had family members and friends who were kind, compassionate folks who never made derogatory statements about people who were different from themselves. So, from a very young age, I knew I had to make a choice: either be racist and xenophobic, or try to be understanding and sympathetic toward people who looked or acted differently from my family members. Of course, I chose the latter, and I use my art to take a stand against bigotry and hatred. And I always will.

Okay, we’ve made it essentially to the end. One last question before you go. What do you understand deeply that most people don’t?

It seems that many people go through life worried about what others think of them, and they let that concern hold them back. They can’t dance unless they’ve had enough to drink. They have to drive a certain car or wear particular clothes to feel accepted or worthy. They feel compelled to project a certain image so that others don’t think of them as “less than.” For me, life’s too short for that. I don’t put those limitations on myself. What’s important to me is to be a good person who cares about others; if someone wants to judge me for the modest car I drive or the well worn T-shirt I’m wearing, I truly couldn’t care less. It’s liberating.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.corybilicko.com

- Instagram: @artistcorybilicko

Image Credits

The photo of me standing in front of the mural (wearing hat and sunglasses):

Photo by Stephanie Fidel

The photo of me leading kids in painting the mural:

Photo by Lori Adamo